To Big Tech, you are a digital commodity. It doesn’t have to sell you anything. Instead, it can sell information about you and what you do online to anyone willing to buy it. Do data on your online activities belong to you, or to the tech companies tracking you? Where does privacy end and commerce begin? It all depends on where you log in. The EU just issued an Online Bill of Rights (GDPR) demanding substantial online privacy and fined Google $5 billion to send a message. America’s least private President doesn’t care about online privacy, doesn’t demonstrate any concern about others privacy, and is moving America in the wrong direction by repealing Net Neutrality. In China, online monitoring is standard. The future of the internet is now being defined and the U.S. government is AWOL. As a result, US tech companies have a golden opportunity to listen to consumers instead of regulators and succeed by focusing on user preferences such as data privacy to in their products.

We should applaud tech entrepreneurs who have created innovative business models that generate valuable assets and charge consumers nothing. But these models require limits, limits that recognize a consumer’s data rights, modest though they currently are. These limits have just been shown, as are the costs of ignoring them. This week Facebook’s shares fell 19 percent, eliminating some $120 billion in corporate value in only two days, a fall partially predicated on concerns over user data and privacy.

Helping tech companies balance the demands of corporate revenues versus user privacy is difficult and a critical debate is raging about the acceptable interests of companies, consumers, and governments regarding online data. Unsurprisingly, the US, EU, and Chinese governments can’t agree on a single standard.

READ MORE: The first casualties of the trade war are Trump supporters

The U.S. polity has traditionally defined and defended the interests of consumers against corporations. In the 1950s, US carmakers dominated world markets, but in 1966 the US government (with a huge nudge from Ralph Nader) demanded that seat belts and other safety measures be installed in all cars. This landmark moment established the global principle of consumer rights at the expense of a hugely successful and largely unfettered industry. The digital analog to this industrial precedent is now being debated in corridors of power worldwide. And again, the Trump administration is AWOL.

The EU has decisively seized the mantle of tech regulatory leadership from the US. In the past, the EU was heavily focused on anti-competitive actions by companies that threatened consumer market choices. Essentially, the US government hatched and nurtured tech corporate giants, while the EU government attempted to control them On July 18, 2018, the EU Commission fined Google $5.1 billion for anti-competitive practices involving its Android mobile platform. This was not first time the EU had challenged US tech companies; in 2017, the EU Commission fined Facebook $129 million, Intel $1.24 billion in 2009, and Microsoft twice in 2008 and 2013 for a total of $1.71 billion. This leaves aside the $15.25 billion the EU forced Apple to pay back to Ireland in EU back taxes or the $293.3 million it demands Amazon pay back for illegal state support from Luxembourg. In tech, the tolerant US government has allowed its tech companies to flourish with minimal regulatory burdens, while the more centralized, bureaucratic EU has responded to these companies with mistrust and constraints.

The EU has now turned its attention to digital privacy and the question of who owns and controls consumer data. On May 25th, 2018, the EU established a new boundary of consumer digital rights when its General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into effect. The GDPR is intended to protect EU consumers and their personal data from commercial exploitation. It requires companies to obtain consent from consumers for the online data they collect, to allow consumers to access the data that is stored, to erase this data at the request of the consumer, and to inform them within 72 hours of a data breach. Breaking these rules will be costly: companies violating these rules can be fined by the EU up to four percent of their global turnover, which is over $4 billion each for Google and Facebook. Both these rules and these enforcement mechanisms are unprecedented in scale.

At the other end of the regulatory spectrum, China’s tech regulatory policies have enabled the state to exert enormous data control and monitoring. China’s new cybersecurity law of June 1, 2017 requires all Chinese data to be stored in China and permits Chinese authorities to perform spot inspections on a firm’s network operations. The Chinese market also poses its own challenges. One of China’s most powerful internet companies, Baidu, was accused of monitoring phone calls on its app without informing consumers, questionable but legal. One man, for example, spoke on his cell phone about picking strawberries. The next day he opened his news aggregator; all of the news stories selected for him were about strawberries.

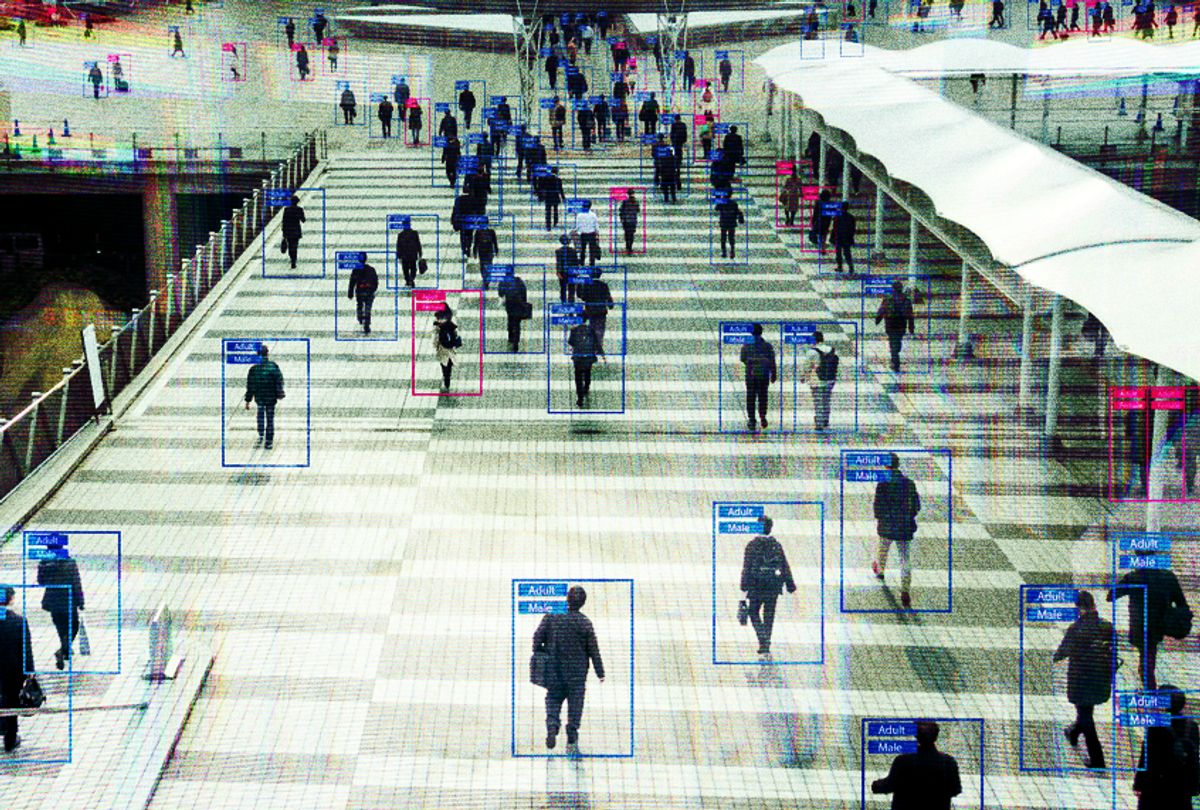

The Internet Society of China reported in 2016 that 54 percent of Chinese web users said they had suffered serious leaks of their personal data and 84 percent said they had been negatively affected by such data leaks. There are an estimated 200 million surveillance cameras in China, four times as many as in the United States, and that number is projected to reach 300 million by 2020. China’s police are forecast to spend up to $30 billion in the next few years on digital surveillance technologies. China’s government holds significant stakes in many of China’s largest tech companies so that the lines between the public and private sector are quite blurry.

READ MORE: the id of Trump the economics of place and our empty national soul

In contrast to the EU’s heavier consumer-friendly regulation and China’s direct market interventions, US policy has traditionally declined to intercede in the US tech ecosystem, implicitly valuing market advancement over consumer concerns. In fact, on June 11, 2018, the Trump Administration repealed Net Neutrality, hobbling what an aggressive expansion of American consumers’ rights. The Trump Administration has offered no analog to the EU’s GDPR on data security and privacy, despite the multiple revelations of leaks and abuse.

Eighty-seven million Facebook users’ personal information were leaked to the UK political consultancy Cambridge Analytica; 145 million customers of the credit bureau Equifax had their personal data compromised; and over 500 million Yahoo accounts were breached by a reported state-sponsored hack. This burden has fallen to the US states, where in June 2018 California passed America’s most aggressive data protection law, despite the strenuous opposition of Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and Amazon (N.B. a last-minute adjustment has delayed the law’s implementation until 2020).

Donald Trump’s dereliction of duty over digital privacy is a crucial opportunity for US tech companies. They can lead a market-driven effort aimed at digital wellness, privacy, and user data safety, just as supermarkets, anticipating pent-up demand, moved aggressively to promote organic foods. Despite the EU’s regulatory leadership, US tech firms can use the vibrancy and innovation of the U.S. market to create new products that surpass the new EU standards. Change to the traditional tech model is inevitable, given the increased emphasis on privacy and data breaches. As governments struggle with regulation, companies courageous enough to seize the moment can redefine the industry.

Shares