Stalking — which is defined by the Justice Department as "harassing or threatening behavior that an individual engages in repeatedly" and involves behavior like following people and harassing them in person, on line or by phone — has been the centerpiece of a couple of news stories that have drawn national attention this summer.

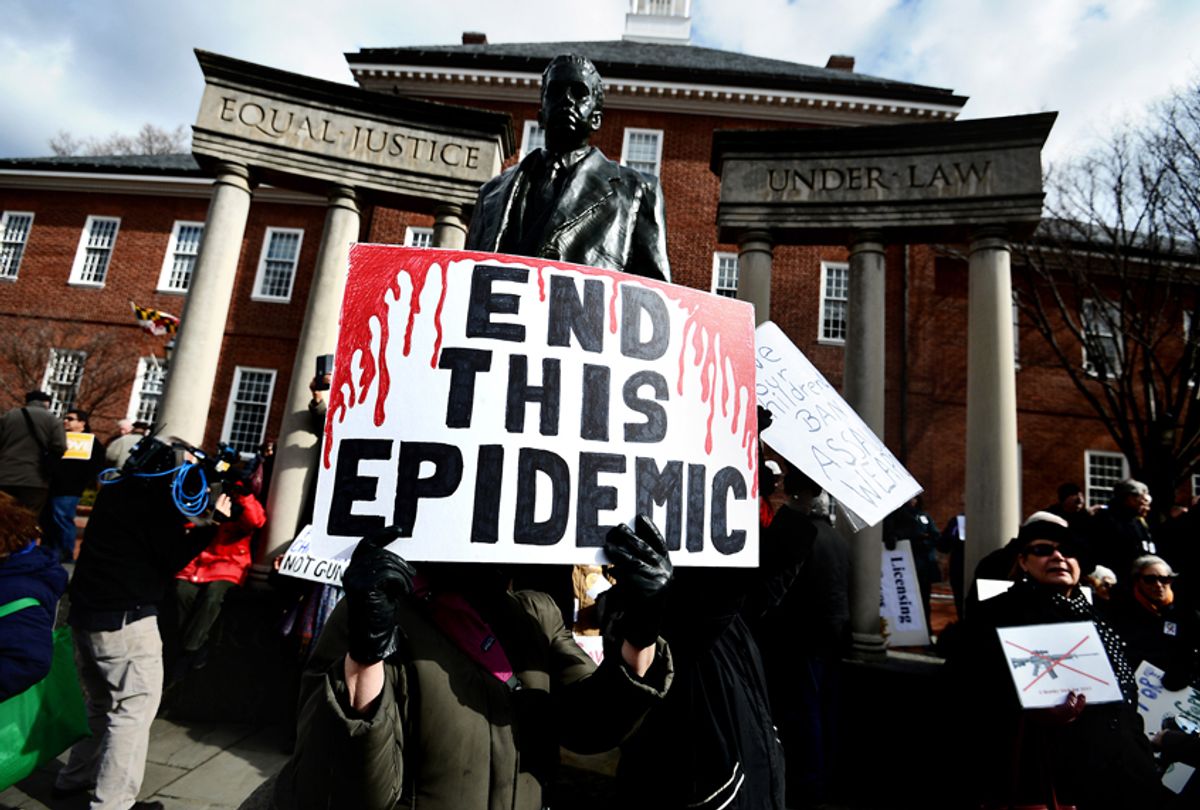

Ohio State University's football program has been at the center of an explosive controversy, due to reports that team leadership, including celebrity head coach Urban Meyer, ignored claims that receivers coach Zach Smith abused and stalked his ex-wife. The June mass shooting at the Capital Gazette newspaper in Annapolis, Maryland, in which five people were killed, was the result of a multi-year obsession by the shooter, Jarrod Ramos, who was convicted in 2011 of stalking a woman with whom he had gone to high school.

The two stories illustrate how serious a crime stalking is, and how terrifying it is for victims.

"I was afraid he could show up at any point, any place ... and kill me," Ramos' stalking victim told NBC News, in an interview where she said she had suspected Ramos was the shooter as "soon as they said it happened at the Capital newspaper and they couldn't identify their suspect."

Courtney Smith, Zach Smith's ex-wife, told the court that her ex-husband had placed secret cameras in her home to monitor her, and that she was repeatedly compelled to call the police because she was being followed by a black SUV. Zach Smith had shown up at her house once at 1:30 a.m., banging on the windows.

“The stalking and harassment never stopped,” Courtney Smith testified. "He would corner me in my laundry while groping me and pulling his pants down and begging for sex.”

“Stalking really is a precursor to other kinds of violence," Ruth Glenn, head of the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, told Salon.

"I was the victim of stalking myself, and ended up being left for dead," said Glenn, who was shot three times by her abusive husband.

Despite all this, the grim reality is that it is still too easy for men with a history of stalking to get their hands on guns, according to a new analysis by Chelsea Parsons at the Center for American Progress. Federal law bans individuals with felony convictions from getting guns. But, as the analysis shows, thousands of people with stalking convictions aren't covered because their crimes are considered misdemeanors.

“Under federal law, individuals convicted of misdemeanor crimes of domestic violence are prohibited from buying and possessing guns," Parsons told Salon. "But that prohibition doesn’t cover previous convictions for misdemeanor-level stalking.”

This is far from the only loophole in federal law that allows abusive men who shouldn't get guns to get them. The federal law banning domestic abusers from buying guns only kicks in if the abuser is married to the victim or lives with her. Gun safety advocates call this the "boyfriend loophole," and have been successful in getting many states to pass laws expanding the federal statute to also cover dating partners.

But while federal statutes need to be updated to cover dating partners, advocates say, they also need to close this stalking loophole.

"In order to prevent domestic violence homicides, we must assess and respond to the risk posed in each case," Kelly Dunne of the Jeanne Geiger Crisis Center told Salon. Her organization has been on the cutting edge of efforts to develop risk-assessment strategies that can prevent domestic abusers from escalating to murder.

"The escalation of violence to lethal levels follows identifiable patterns with identifiable indicators," Dunne explained. "Stalking is often the last crime a victim experiences prior to being killed."

"This study shows that our weak gun laws put stalking victims at risk for future gun violence," Jonas Oransky, the legal director of Everytown for Gun Safety, told Salon. He noted that Moms Demand Action, which partners with Everytown, has "spent years supporting bills to disarm domestic abusers, including prohibiting people convicted of misdemeanor stalking," and has gotten such bills passed even in Republican-controlled state legislatures.

Because these stalking or harassment convictions are misdemeanors, it may seem tempting to dismiss them as minor crimes that don't merit a lifetime ban from firearm ownership. Many experts feel that underrates the threat level.

Designating such an offense as a misdemeanor "doesn’t really speak to the full scope of the risk posed by that person," Parsons said.

“Enforcement is very difficult," Glenn said, explaining that many stalkers are not get charged correctly in the first place because "unless you have an extremely experienced first responder," police officers may not even recognize the behavior as criminal.

Even when someone is charged with stalking, she added, the perpetrator is often able to plead down to a misdemeanor: "Lawyers are very good at minimizing what is stalking."

In addition, Parsons said, "You often have a situation where you have a reluctant survivor who really doesn’t want to engage in a prolonged proceeding." She may accede to a stalker pleading down to a misdemeanor in hopes that she can just move on with her life.

The Ramos and Smith cases illustrate this problem. Ramos pled guilty to a misdemeanor harassment charge in 2011 and received probation, which was why he was legally able to buy the gun he used to kill five people.

When Zach Smith was arrested for criminal trespassing in 2017, it was after building up a years-long record of police calls that had not resulted in arrest. Still, the charge is only a fourth-degree misdemeanor, which fails to capture what Courtney Smith says was a violent relationship that included an incident where she says her former husband "took me and shoved me up against the wall, with his hands around my neck."

“We’re very well aware that behavior escalates over time, and if we have not been able to remove that gun when we should have, the risk escalates pretty quickly and pretty high," Glenn said, noting that the risks are not just to the stalking victim but "to others in her world, to the community at large."

The Annapolis shooting is a good example, as Ramos' obsession with his victim ballooned into an obsession with the staff at the Capital Gazette for daring to report on his behavior in the first place. But stalking can often be a precursor to mass shootings. Seung-Hui Cho, the Virginia Tech shooter, had been reported to the police for stalking and hadn't been charged. Nikolas Cruz, the Parkland, Florida, shooter, reportedly stalked at least one fellow student. Devin Patrick Kelley, who murdered 26 people in a Texas church last year, had a long history of stalking women.

READ MORE: Right's attack on birthright citizenship: A new front in the battle for the Constitution

Glenn said that while people often use the word "obsession" to describe stalking, she felt it was better understood as a "need for control." That's why it's such a precursor to violence, and sometimes mass murder. The stalker's frustration at not being able to control his target mounts, and he becomes angrier and starts looking for more ways to control others. In the worst instance, that can lead to murder, the ultimate act of control over another person.

The solution to this problem is twofold. Law enforcement needs to take stalking more seriously, instead of shrugging off harassing behavior as a minor inconvenience or a minor excess on the part of a lovestruck man. State and federal governments should close the stalking loophole, so that misdemeanor stalking, harassment or trespassing charges lead to a permanent ban on purchasing weapons.

"It’s critical that the systems listen to victims when they are being stalked," said Dunne, "and employs risk management strategies that bring systems together to create real solutions for victims."

Shares