At last weekend's Newport Folk Festival, Jason Isbell & The 400 Unit's Friday set featured a marquee special guest: David Crosby, who performed Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young's "Ohio" with the band. Isbell has covered the song before in concert multiple times, but this version unsurprisingly had extra grit and exuded a grimmer tone that was mesmerizing. Isbell and Crosby's harmonies were weary but wise, and the performance's multiple-electric guitar approach added tenacity. It didn't feel like a song nearing 50 years old; it was vital contemporary commentary.

Later in the weekend, Leon Bridges, Gary Clark, Jr. and Jon Batiste gathered to do their own live cover of "Ohio." In contrast to the version performed by Isbell and Crosby, the trio's take on the song was sparse, driven by hypnotic vocal harmonies, ominous percussion and sinewy guitar. This "Ohio" was closer in tone to the studio version of the song they released in 2017 as part of a Spotify playlist called "Echoes of Vietnam" — and it was just as moving and meaningful as Isbell and Crosby's take, as it amplified the song's mournful underpinnings and smoldering grief.

"This is something I’ve always dreamed of, coming together with these guys," The New Yorker quoted Clark, Jr. discussing the song. “It’s powerful. Three young black men coming together and making good music and making a statement.”

That both groups of musicians chose the Newport Folk Festival to reprise "Ohio" was perfect, as activism has been an intrinsic part of the event's DNA since its inception. In fact, you might say that Newport has strived to amplify those pushing for social change since day one. In 1963, a performance of "We Shall Overcome" featured every musician at the fest, including the Freedom Singers, a quartet whose music anchored the civil rights movement, while in 2017, a "Speak Out" set highlighted modern activism and political protest in a post-Trump world.

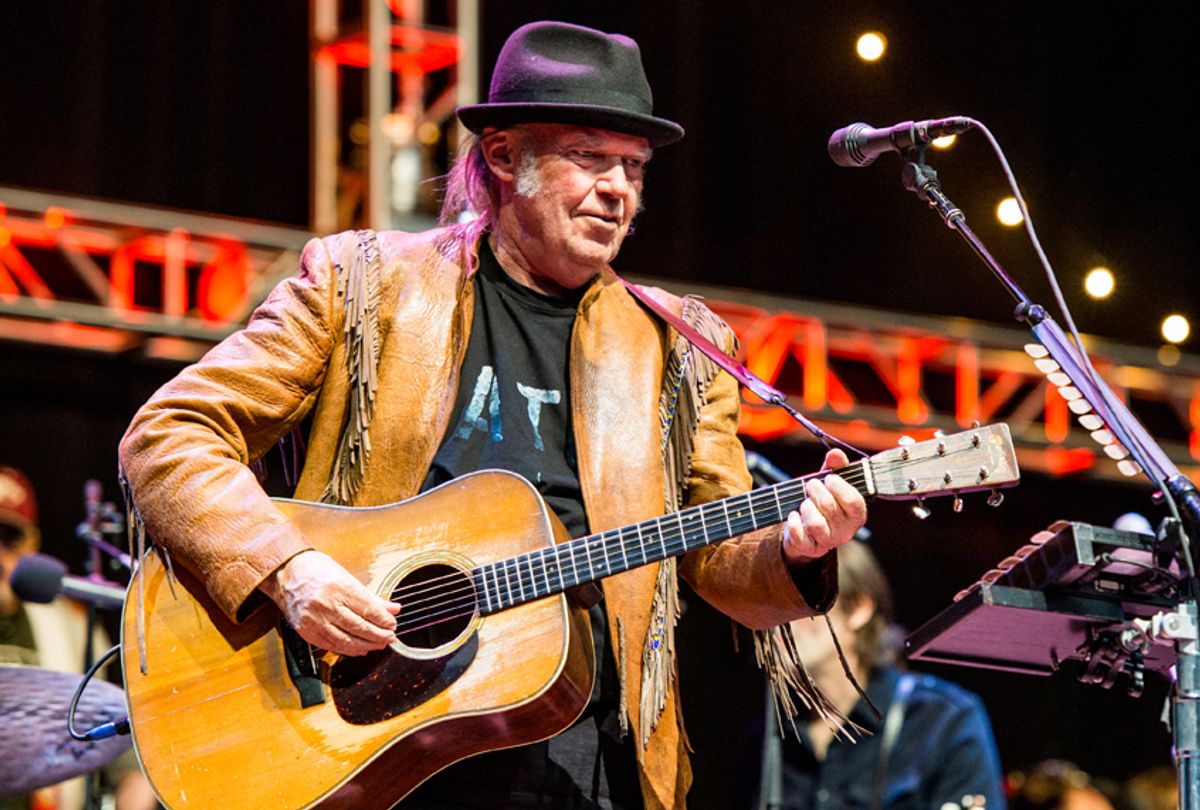

But the very act of covering "Ohio" — which the headline of a 2010 The Guardian article dubbed the "greatest protest record" — feels especially poignant in 2018. Written by Neil Young after seeing a Life magazine story about the May 4, 1970, massacre of four students at Kent State University by members of the Ohio National Guard, "Ohio" retains its power.

Besides grappling with the implications of the horrific event, the song expresses anger, disbelief, shock — and an irrevocable sense of betrayal, that those in power are now officially an enemy, actively working against the will of the people and resorting to violence to quash dissent. The simple, dateline-like lyric "Four dead in Ohio," which repeats throughout, cements the song's inspiration, ensuring that those killed are never forgotten.

READ MORE: Kate Bush at 60: An exquisite pop genius whose influence endures

The specificity of that line also ensures the Kent State massacre isn't forgotten. "A large part of the reason many people know about Kent State as they do is because the song 'Ohio' brings it to people who are not necessarily researching the Nixon era," journalist Dorian Lynskey told The Atlantic in early 2018. But unlike many protest songs, which feel inextricably tied to their time, "Ohio" transcends eras. While originally written about one particular incident, the song eventually came to reflect much greater truths about violence, power dynamics and oppression.

Its themes especially feel resonant in a post-2016 election world, with a news cycle dominated by stories of an administration hostile to historically marginalized communities — including (but not limited to) immigrants, the LGBT community, black Americans, the disability community and women. "Ohio" also has deep ire for senseless violence and expresses feeling helplessness while watching someone innocent become collateral damage — sentiments that are certainly familiar to the current movement against gun violence.

Of course, "Ohio" wasn't always embraced for its message or foresight. The song was famously banned from some radio stations, while Devo's Gerald Casale, who was at Kent State on May 4, is quoted in "Shakey: Neil Young's Biography," as saying, "We just thought rich hippies were making money off of something horrible and political that they didn't get."

Casale didn't mention "Ohio" in a recent Washington Post article, which went in-depth about the impact the Kent State shootings had on members of Devo and the musician Chris Butler, who later found success with the Waitresses. But Casale did detail how that May day affected him: "I don't think I would have started Devo had that not happened. It's that simple."

He wasn't the only musician changed. In her memoir, "Reckless: My Life as a Pretender," the Pretenders' Chrissie Hynde wrote about how being on campus that day shaped her worldview, while in the biography "Divided Soul: The Life Of Marvin Gaye," the soul/R&B icon also connects the Kent State shootings to his thought process prior to recording the landmark album "What's Going On."

"My phone would ring, and it'd be Motown wanting me to start working and I'd say, 'Have you seen the paper today? Have you read about these kids who were killed at Kent State?'" he said. "The murders at Kent State made me sick. I couldn't sleep, couldn't stop crying. The notion of singing three-minute songs about the moon and June didn't interest me. Neither did instant-message songs."

The urgency of social commentary also underlines the protest music that's alive and well in 2018. Interestingly enough, "Ohio" also remains a live staple today, across multiple genres and generations. Although it's an imperfect source, setlist.fm shows a noticeable uptick in reported performances of "Ohio" from 2016 through the present day. These include covers by artists such as Isbell, Phil Lesh & Friends, Whitehorse, and Blackfoot, as well as versions done by Young, Crosby and Graham Nash during their respective solo shows.

You can chalk this increase up to more solo shows by CSNY's principal members, of course. But "Ohio" is an enduring reminder of both a dark time in U.S. history — and why it's important that these times are never forgotten.

"For years I couldn't sing it," Young said of the song in 2006, "because I felt I was kinda taking advantage of something that happened and we were trading on somebody's misfortunes … to give the audience a kind of rush of nostalgia … In this period of time, that doesn't apply. What it is now is, it's a history. We're bringing history back. That's what folk music does."

Shares