In 2013, when I joined the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), my local Oakland chapter had 20 active members, the youngest of whom was 35 years older than me. Though I was happy to be involved, I can’t say I felt like I had much in common with the rest of the group: I was young, broke, bitter about how the still-present recession had stunted my career growth and prospects. Yet I didn’t have a shared language to talk about this with the older comrades in the chapter, who were largely retired.

Four years later, shortly after the U.K.’s snap election, I was at a bar with members of DSA's San Francisco chapter — which was nonexistent in 2013, but now has around 800 members — when the chapter broke out into a spontaneous chant of “Oh, Jeremy Corbyn,” sung to the tune of the bassline in The White Stripes’ “Seven Nation Army.” I recognized the chant and was able to sing along by virtue of having previously heard it on Twitter. The demographics of DSA had reversed since 2013: the chapter was largely people my age, in their 20s and 30s, and many of the people in my vicinity I’d met or interacted with on Twitter before ever meeting IRL.

Having foreknowledge of a Jezza chant may seem like small potatoes, yet it is astonishing for what it says about how leftist political culture has changed throughout the 2010s. Nowadays, there is a vast “Rose Emoji Twitter” subculture (roses being the symbol of democratic socialism and of the DSA); and it is no longer confined to online, but leaking out into the real world, with its own mores, memes and slang. That world was confined to the Internet, and then grew to the podcasting world, and now the vanguard podcast associated with the online left has its own manifesto.

For the uninitiated who may not be familiar with Rose Emoji Twitter, it’s easy to find: simply scroll to the Twitter page for any centrist or right-wing pundit, and then flip through replies to their bad tweets. You’re guaranteed to find dozens of Twitter users with rose emojis and portmanteau user names like “Frank Black Mirror” or “Antonio Banshee” mocking and belittling these pundits’ jejune neoliberalism or reactionary conservatism. To wit:

Which brings me to Chapo Trap House’s new book. If you are unfamiliar, the 2-year-old podcast is probably the exemplar par excellence of what the commentariat refers to as the “Dirtbag Left,” a mostly-online culture of leftists who eschew the niceties of liberal cable-news discourse. Chapo's modus operandi has always been halting the enabling of ghouls, both right-wing and neoliberal: no more respectability politics for people unworthy of respect. And it's a fitting movement for the political moment, given that the Republican Party has drifted so far off the deep end that their politicians are parroting white supremacist talking points.

The Dirtbag Left is, like the Dadaists of yore, adept at satirizing and exposing the absurdities of a political culture where horrors like drone bombings, children in cages, and glowing profiles of Nazis in the pages of the New York Times are quotidian occurrences. Unlike the Dadaists, however, the Dirtbag Left’s skewering of the commentariat is achieved largely through podcasting and posting. Indeed, Twitter is an ideal public platform for mocking and skewering the powerful, and which four of the five Chapo hosts — Amber Frost, Felix Biederman, Will Menaker, Matt Christman and Virgil Texas — are particular adept at.

To say that Chapo Trap House's podcast is successful or popular would be an understatement: currently, they are the most popular creators on crowdfunding site Patreon, and bring in over $100,000 per month from online subscribers who individually pay $5 a month to listen to their premium episodes (every week they produce one free and one premium episode). In a recent podcast episode, co-host Will Menaker mentioned that an average free episode gets 150,000 listeners.

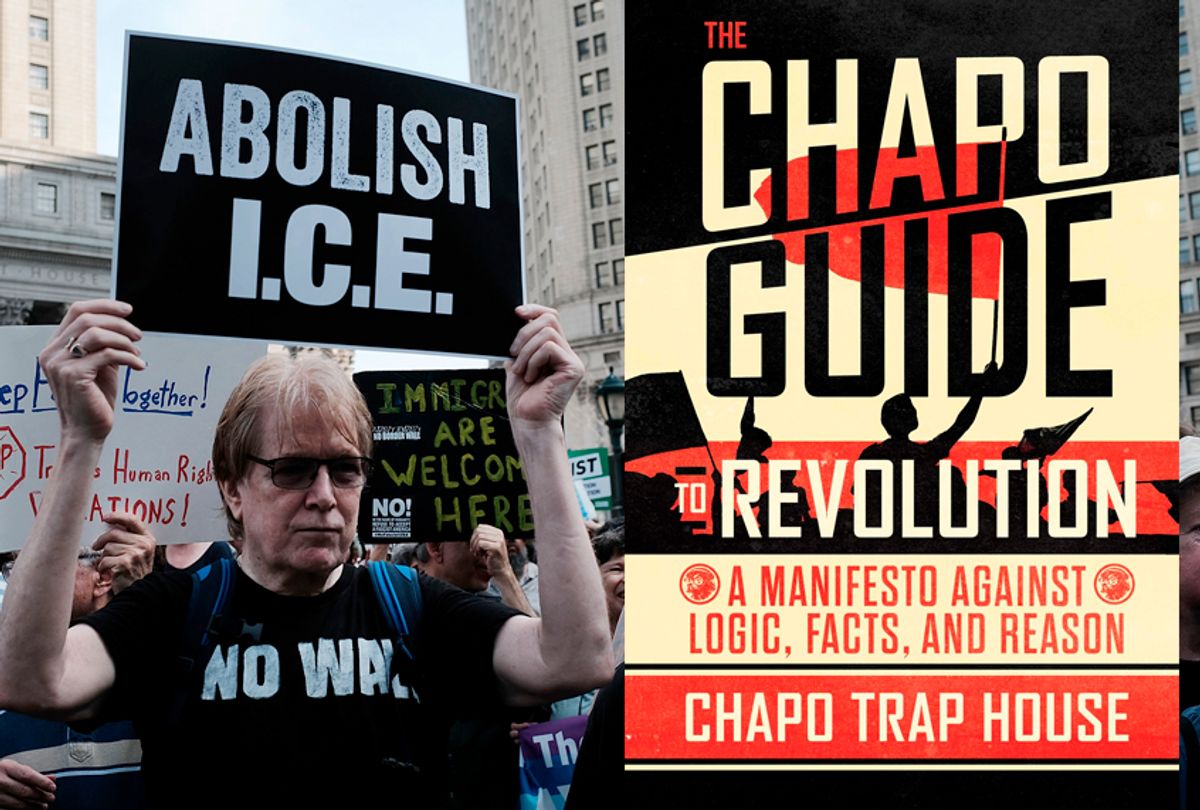

As perhaps the epicenter of the online left, Chapo Trap House has, to paraphrase Spider-man’s uncle, great power and thus great responsibility. Fittingly, the five hosts have produced a new book, “The Chapo Guide to Revolution: A Manifesto Against Logic, Facts and Reason,” as a literary salve in the ongoing culture wars. It is, I think, the most articulate (and irony-laden) mission statement for the online left today, mapping its place in American culture at large.

If you are familiar with other book adaptations of political comedy shows, such as any of Stephen Colbert or John Stewart’s volumes from earlier in the millennium, “Chapo Guide to Revolution” will seem familiar (though the politics are obviously different from Colbert's or Stewart's). The Chapo book is a wry, satiric look at American political culture, interspersed with asides and factoids that layer over the larger narrative. One of my favorite sub-sections, the “Chapo Trap House World Fact Book,” recalls the CIA World Factbook as filtered through the Chapo narrative, e.g. “Russia. Population: 144 million bots. Chief Exports: Tracksuits, Misery, Important Novels.”

True to its title, the book is indeed a “guide” in the sense that it provides a greater vision of the United States today from the point of the view of a burgeoning left-populist movement largely coalescing online and vis-a-vis DSA. In that sense, the most important subsection is the illustrated guides to conservative and liberal archetypes: Even a casual reader with no Twitter account and no online presence could flip to the center of the book and scan these to get a sense of how disaffected millennial leftists (self included) see the world. Conservative archetypes that Salon readers will be familiar with include “Liberty Babe” (“a conservative media personality who appeals to an audience of mostly Social Security–age men hungry for books that reinforce their cosseted worldview and whose jackets give their lonely trouser worms a jolt of life”) and “Bow-Tie Dipshit” ("a very specific subset of right-wing anti-intellectual intellectual, the Bow-Tie Dispshit represents the upper crust of the conservative movement.)” Liberal archetypes include the “Corporate Feminist” and the “App Hole” (“He hopes someday to totally eliminate the obsolete operating systems of unions, education, and public sanitation.”)

This speaks to one of Chapo Trap House’s greatest talents: specifically, that by situating themselves further to the left and thereby skewering both liberals and conservatives, they are able to subvert the hegemonic liberal notion that there is some holy “center” to which all two-sided discourses must hew. The CNN-esque norm of bringing a conservative and a liberal to debate on-air might have worked back in the 1970s, but as the country drifts right, this obsession over an imagined “center” can actually be harmful in its tendency to normalize totalitarianism. Chapo Trap House's five hosts understand this, and thus spend much of the book, and their podcast episodes, sounding the alarm bells.

The point is, the Chapo book — along with the podcast, and the culture around Rose Emoji Twitter — are important for what they foreshadow for our political future. The Chapo hosts may not have created the Dirtbag Left, but they have been at its vanguard, and around them a constellation of other artists, writers, critics, Leftbook pages and casual Twitter trolls have been born. Politics is not merely about protests and voting, but is also about desire, relationships, culture: few will join a movement that is not accompanied by a vision of the future, or which can laugh at itself. Emma Goldman’s now-cliché quote, “A revolution without dancing is not a revolution worth having,” is applicable here.

This is, I think, what makes "Chapo Guide to Revolution" particularly important. The book’s articulation of US hegemony is more or less what you might find in a Chomsky book or Howard Zinn’s “People’s History of the United States,” yet it is written in an argot that will be instantly recognizable to any millennial or GenXer who spends time online. This is more revolutionary than it sounds: reading the book, I can picture how, say, a 20-year-old suburban college student slacker failson — who, in another epoch, would gravitate towards libertarianism (the default of white suburban college males) — might see this book on his roommate’s shelf and read it in one sitting. That’s important, as a lot of people out there might never read Chomsky or Zinn or Angela Davis — dense, depressing politics books just aren’t everyone’s thing — but would read this book because it’s accessible, funny, and in a language and a culture that they understand. Chapo Trap House are not merely critics, but are also helping to build a culture that is introducing many new people to leftist politics in an accessible way.

In this dark political moment it may be hard to imagine, but there is actually historical precedence for the notion that artists, critics and humorists might help mainstream leftist culture and thus drive political change. In 1913, striking silkworkers from Paterson, New Jersey, joined with Greenwich Village writers and artists at Madison Square Garden in New York for what was perhaps one of the country's first benefit concerts — and an event that, in the words of Yale historian Michael Denning, “inaugurated a new relation between the left and the producers of culture."

Within 20 years, as Denning explains in his tome “The Cultural Front,” the American left wasn’t just a bystander in the culture wars; they were actively involved in creation — meaning art, literature, music -- in a manner that reflected the burgeoning populist tide. Denning calls this the emergence of a “left culture,” one that would become so powerful as to push the country towards the New Deal and result in a labor movement that beat back the robber-barons’ hold on both wealth and power for decades.

Politics and culture are not separate: television, books, comedy, and film have their own cultural politics that we absorb in consumption. Children and adults learn how to interact, relate and think via what they watch and read, sometimes to deleterious effect. I absorbed what the mores of dating culture were by watching “Friends” with my sister when I was a tween, learning patriarchal norms that took years to unlearn. There was no alternative because there was no internet culture when I was kid — no Twitter left I could be a part of and where I could learn alternative, less oppressive culture mores and ways of interrelating.

Later in his book, Denning explains how this specific merger of culture and politics in the 1910s and on constituted what he calls a “historical bloc,” recalling the Italian Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci. A historical bloc refers to an alliance between the social and the political; it is a way of thinking about the world that appears in both the political and the cultural sphere. The historical bloc of the early 20th century resulted in the New Deal and the ongoing labor movement that created middle-class prosperity for a good sixty-plus years, and which, despite being rampantly chipped away at by the right, still sustains and provides a safety net for hundreds of millions today.

This is, then, what makes the Twitter left at large so important for the future of culture and politics. "The Chapo Guide to Revolution" functions as an accessible entry point, both for the always-online set and the never-online set — though the latter may want to approach it with Urban Dictionary on-hand, otherwise, sentences like “America, Reagan’s shining city on the hill, vanished in a cloud of Choom smoke” may not be entirely clear.

I suppose one might constitute that as a weakness: If I gave this book to my Boomer parents, they would have no idea what was going on. I think the Chapo hosts would freely admit this; they are openly self-critical about how their audience skews towards white guy failsons in their 20s and 30s. There’s nothing innately wrong with that — obviously, our country would be much better off if young white men gravitated towards the left rather than the right — though it also speaks to how the book, and perhaps Rose Emoji Twitter in a larger sense, thrive among specific identities.

I wonder if someday this book will be remembered as an early entry in a burgeoning early 21st century leftist cultural movement in the United States. Vernon Lidtke, in his book “The Alternative Culture,” explains how Germany’s 19th century and early 20th century socialist movement was effective in part because it transcended the bounds of mere political parties. Lidtke describes socialist singing societies, workers’ gymnastic clubs, and worker cyclist groups in Germany at the time. The Second International, the SPD in Germany, and ultimately the German Revolution of 1918-1919 — in which Rosa Luxemburg’s socialists were inches away from taking power — resulted from this merger of culture and politics. To paraphrase playwright Bertolt Brecht, who emerged from that era, art is not a mirror, but a hammer.

# # #

[Editor's note: the author worked indirectly with Chapo Trap House co-host Amber A’Lee Frost when organizing with DSA online in 2013 and 2014.]

Shares