As Paul Manafort — the political consultant best known for his five-month stint as President Donald Trump’s campaign manager during the 2016 election — continues to stand trial on criminal charges, a second character has emerged as the dominant force whose whims could play a decisive role in shaping the next stage of the lengthy, labyrinthine legal saga of the Trump-Russia scandal.

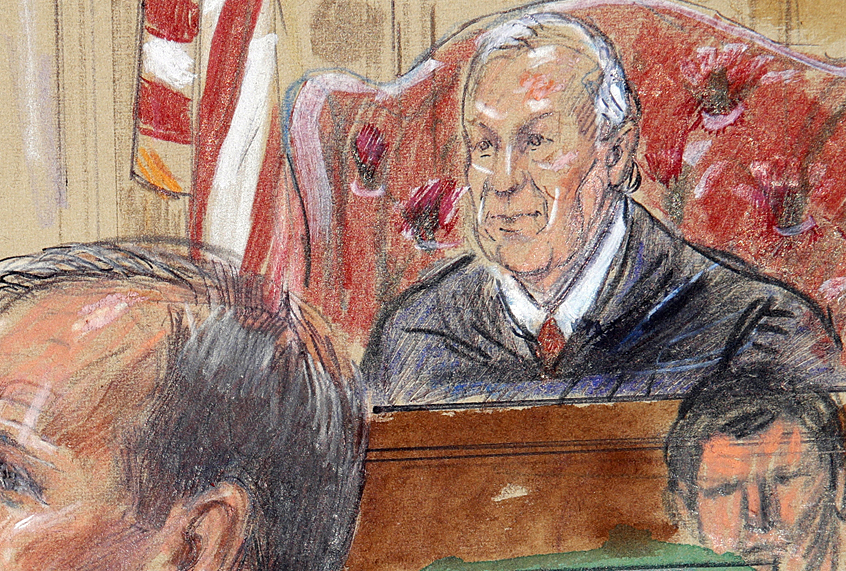

It is not Trump, himself. Nor is it special counsel Robert Mueller: the man overseeing the investigation into allegations of collusion with Russia that continue to follow Trump’s campaign. In fact, the emerging star here seems to be U.S. District Judge T. S. Ellis, whose ongoing jibes follow a reputation for being tough on attorneys, yet seem to be disproportionately aimed at Mueller and those who criticize the president.

“As the proceedings enter their second week, the indisputable center of attention so far is the judge, T.S. Ellis III, whose cantankerous, jocular, impatient and verbose presence has shaped each step of the way,” wrote the Los Angeles Times. Appointed to the bench by former President Ronald Reagan in 1987, Ellis has been outspoken from the get-go about his skepticism regarding Mueller’s probe of Manafort, earning fulsome praise from Trump in the process.

In May, Ellis reprimanded Mueller’s prosecutors by declaring that “you don’t really care about Mr. Manafort’s bank fraud. You really care about getting information Mr. Manafort can give you that would reflect on Mr Trump and lead to his prosecution or impeachment,” according to The Guardian. The judge later added, “We don’t want anyone in this country with unfettered power. It’s unlikely you’re going to persuade me the special prosecutor has power to do anything he or she wants. The American people feel pretty strongly that no one has unfettered power.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Trump offered up Ellis’ remarks as evidence that the special counsel’s entire investigation was a partisan crusade against him, or a “witch hunt.” The president even described Ellis as “something very special.” However, if knowing that the president views him as his cheerleader worried Ellis, he has not given any indication.

On two occasions, the judge interrupted Assistant U.S. Attorney Uzo Asonye to criticize his opening statement in the trial. Ellis has also unloaded on Mueller’s team for dwelling on the details of how Manafort allegedly spent his ill-gotten gains. He also rushed prosecutors through questions amid their meticulous attempts to connect key dots in their case, including an effort to illustrate how an invoice appeared to have been falsified.

On at least one occasion, Ellis also criticized one of Manafort’s defense attorneys for seeming slow to object to a prosecutor’s question. Earlier in the trial, he took issue with the Manafort team’s claim that detaining their client in the Alexandria Detention Center would present unspecified safety concerns, according to USA Today.

“Defense counsel has not identified any general or specific threat to defendant’s safety,” Ellis wrote. “They have not done so, because the professionals at the Alexandria Detention Center are very familiar with housing high-profile defendants, including foreign and domestic terrorists, spies and traitors.”

READ MORE: Right’s attack on birthright citizenship: A new front in the battle for the Constitution

In fairness, Ellis has an indisputably stellar professional résumé. This summary from the Los Angeles Times’ coverage of the trial clearly illustrates his qualifications:

He holds an engineering degree from Princeton University and law degrees from Harvard Law School and the University of Oxford. He served in the Navy from 1961 to 1967, then worked in private practice at the Richmond, Va., law firm Hunton & Williams for nearly two decades before Reagan appointed him to the bench in 1987. At the firm, he overlapped with Lewis F. Powell, who was a prominent partner until he was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1971.

High-profile criminal cases have punctuated Ellis’ 31-year career as a federal judge, including the trial of “American Taliban” John Walker Lindh, an American citizen who traveled to Afghanistan to train with Al Qaeda and was captured during the 2001 U.S. invasion. Lindh accepted a plea bargain and Ellis sentenced him to 20 years in prison without parole.

It is reasonable to conclude that Ellis, above all else, likes to present himself as a judge who keeps the lawyers in his courtroom on their toes. He has a reputation for creating a “rocket docket,” in which he attempts to trim the fat from proceedings that seemingly drag on, cracking self-deprecating jokes that help jurors stay engaged at times when they might otherwise be bored. The judge is also widely regarded for having a sharp mind and highly-detailed knowledge of the law.

However, some of Ellis’ actions prior to and during Manafort’s trial have raised questions. Given that he was appointed to the bench by Reagan, it would not be unreasonable to ask if it is possible that Ellis possesses a bias toward Republicans. According to CNN, the judge has a reputation for leaning toward conservative viewpoints in his rulings. And, in May, Ellis made a point of casting doubt on Mueller’s authority to prosecute Manafort before ultimately allowing the prosecution’s case to advance to trial. Critics might wonder if Ellis gave the pro-Trump crowd political ammunition with those musings.

Moreover, some of Ellis’ admonitions against Mueller’s team have arguably stretched the bounds of what might be considered reasonable attempts to avoid prejudicing jurors. A notable example of this occurred when Ellis scolded prosecutors for referring to the powerful Ukrainian businessmen who paid Manafort as “oligarchs” – a term he argued had a “pejorative tone,” which would unfairly slant the jurors against the defendant. While it is reasonable to not want jurors to be unfairly prejudiced toward or against a defendant’s guilt or innocence, should a judge go so far as to not allow the government to refer to an oligarch as such?

None of this is meant to imply that Ellis is an improper judge or that he is deliberately skewing the Manafort trial due to potential pro-Trump biases. It could simply be that Ellis is a colorful personality who has, inevitably, shaped these proceedings by his individual idiosyncrasies as much as by his knowledge of the law. At the same time, in an era where hyper-partisanship seems to be ever more frequently overriding the call of justice, Americans cannot be too vigilant in making sure that the people who claim to be impartially presiding over our legal system are, in fact, impartial.