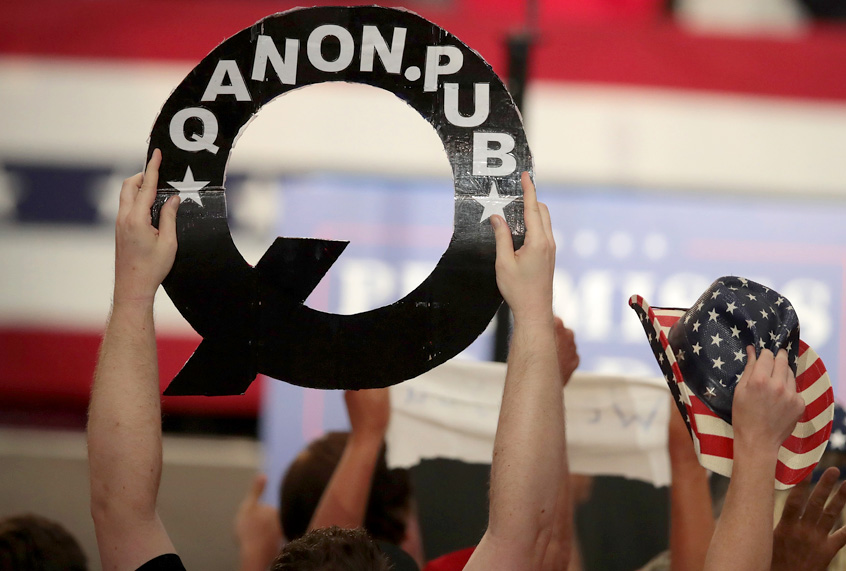

You have likely heard of latest right-wing conspiracy theory “QAnon” by now since it has hit the mainstream media. Not only does it have many of us on the outside questioning how we got here as a society, but it also raises peculiar questions about the human condition. Why are some people more prone to believing conspiracy theories than others?

If you are unfamiliar, QAnon — sometimes referred to as “the Storm” — is a pro-Trump conspiracy theory that has created a cultish culture on the internet. It began when a pseudonymous ring leader calling themselves “Q” began posting on the anonymous internet forums 4Chan and 8Chan in late 2017 (hence the name “QAnon”). The conspiracy theory itself is long-winded and slightly complicated, but it boils down to this: Q claims to have uncovered evidence that high-profile Democrats are pedophiles, and President Donald Trump is leading the fight against the group. Q communicates to his followers through obscure “crumbs.”

In other words, it takes the Pizzagate lie to the next level, and the level of absurdity raises the question of whether we are all being trolled. BuzzFeed has made the case that a leftist prankster could be pulling an elaborate prank on Trump supporters with QAnon. Whoever QAnon is, though, some of his followers have proven to be devoted through the so-called conspiracy in dangerous ways. In June, a group of Arizona veterans thought a homeless camp was a child-sex camp, which led to local authorities seriously investigating the claim. In July, Michael Avenatti was targeted by QAnon.

We are trying to identify the man in this picture, which was taken outside my office yesterday (Sun) afternoon. Please contact @NewportBeachPD if you have any details or observed him. We will NOT be intimidated into stopping or changing our course. #Basta pic.twitter.com/YIKS6D0Grq

— Michael Avenatti (@MichaelAvenatti) July 30, 2018

Americans with far-right political views are no strangers to conspiracy theories. Alex Jones of Infowars is notorious for spreading them, and he has millions of followers. While there is no direct and clear answer as to why some people believe in conspiracy theories and others don’t, a group of psychologists have narrowed down a few possibilities.

“There are many factors that draw people toward conspiracy theories. Some of them are related to aspects of a person’s personality (e.g., narcissism, Machiavellianism, mistrust) and others are associated with social factors (e.g., powerlessness, education, age),” Karen Douglas, a Professor of Social Psychology at the University of Kent, Canterbury, told Salon in an email.

In 2017, a group of researchers including Douglas at the University of Kent published a paper titled “The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories,” in which they suggested conspiracy theories are driven by three factors: epistemic, existential and social.

“First, conspiracy beliefs are linked to the way people process information. People have a higher tendency to believe in conspiracy theories if they feel uncertain and are motivated to find meaning or patterns in their environment,” Aleksandra Cichocka, another one of the authors and a Senior Lecturer in Political Psychology School of Psychology at the University of Kent told Salon in an email. “Conspiracy beliefs are also linked to lower levels of analytical thinking.”

The second reason relates to existentialism.

“Conspiracy beliefs increase when people feel anxious, powerless or that they lack control over their lives,” she said. “In these situations, they might be motivated to think that someone else is ‘pulling the strings’ (as Douglas and others put it).”

Regarding the possible third reason, “social,” it might have to do with a deep desire to belong to a group.

“And third, conspiracy beliefs are linked to the need maintain a positive image of oneself and the social groups one belongs to,” she said. “For example, belief in conspiracy theories is higher among members of marginalised or disadvantaged groups. Presumably, believing in a conspiracy allows them to place blame for any negative experiences on others.”

But what is it about the far-right that encourages such wild theories to spread? As Cichocka explained, there is evidence that the far-left is likely to believe in conspiracy theories too. Indeed, the popularity of conspiracy theories aren’t linked to a specific group, but rather to “extremists.” A 2014 study by University of Chicago political science professors Eric Oliver and Thomas Wood found that each year they surveyed samples of the population, half of Americans believed in a conspiracy theory. Specifically, 24 percent of Americans (at the time of the study) believed former president Barack Obama was not born in the United States and 19 percent of Americans believed the U.S. government was responsible for 9/11.

“It could [be] that extremists on both sides are drawn to conspiracy theories, especially if they feel marginalised or disadvantaged,” she said. “Thus, if far-right conservatives felt marginalised in the US, this might have created a fertile ground for conspiracy theories.”

“In the end, believing there is a conspiracy can help people explain why they are not getting the recognition they feel is due to them,” she added.

READ MORE: Facebook de-platforming Alex Jones may be too little, too late

Douglas explained once someone believes in a conspiracy, it can be hard to change one’s mind (although it is possible to “inoculate” one).

“In general, once ideas become fixed, they are difficult to shake off,” Douglas told Salon in an email. “So once a person believes in a conspiracy theory it is difficult to convince them otherwise.”

“Alternative explanations are often quite mundane too and conspiracy explanations tend to be more proportional to the events themselves, which makes them more interesting,” she added, noting more research needs to be done on this topic.

Today’s hottest topics

Check out the latest stories and most recent guests on SalonTV.

TRENDING