For Jason Kessler, the 34-year-old organizer of this weekend’s Unite the Right 2 event — a white-supremacist gathering in Washington, D.C., to mark the anniversary of last year’s deadly rally in Charlottesville — things immediately started off on the wrong foot and only got worse from there.

On Sunday afternoon, in the parking lot of the Vienna/Fairfax GMU Metro Station, where he and his cohort had planned to assemble, it quickly became clear that the size of their gathering had been grossly overstated: only a few dozen of his fellow protestors had showed up, far less than the predicted 400. Moments later, as he tried to board the train to Washington, D.C., Kessler was told to dispose of all flagpoles — he’d asked participants to carry Confederate and American flags—which the officer in charge patiently explained could be wielded as weapons and were thus prohibited.

“What?” Kessler responded. In black sunglasses and an ill-fitting blue suit, he pleaded, “You guys can’t make an exception for us?”

A half-hour later, at the Foggy Bottom station, to which he and the other white nationalists traveled via police escort in a special Orange Line car, Kessler emerged beneath the steamy Seaboard afternoon to face yet another embarrassment: he’d arrived much earlier than planned. At the time it was just before 4 p.m.Their march along Pennsylvania Avenue wasn’t supposed to begin for another hour (the rally was scheduled 5:30–7:30 p.m.). But by now they were already too far along. And in a state of heat-weary bewilderment, they plodded the half-dozen blocks to Lafayette Square, where Kessler and the members of his small group — some of them wearing bright red Make America Great Again baseball hats — found themselves face-to-face on all sides with a jeering cacophony of counter-protestors numbering in the thousands.

These counter-protestors carried signs that read THIS IS NOT THE TIME FOR CIVILITY. And: DOWN WITH THIS SORT OF THING. And: FREE HUGS FROM A QUEER BLACK JEW. And: LOVE IS LOVE IS LOVE IS LOVE IS LOVE IS LOVE. They clapped and booed. They sang hymns. “It’s hot, it’s wet, but we aren’t done with Nazis yet,” they chanted. Around white nationalists — who at Lafayette had been immediately cordoned off by police on horseback — this dense human sea crackled and tensed, so that it was difficult to glimpse, let alone hear, Unite the Right’s featured speakers.

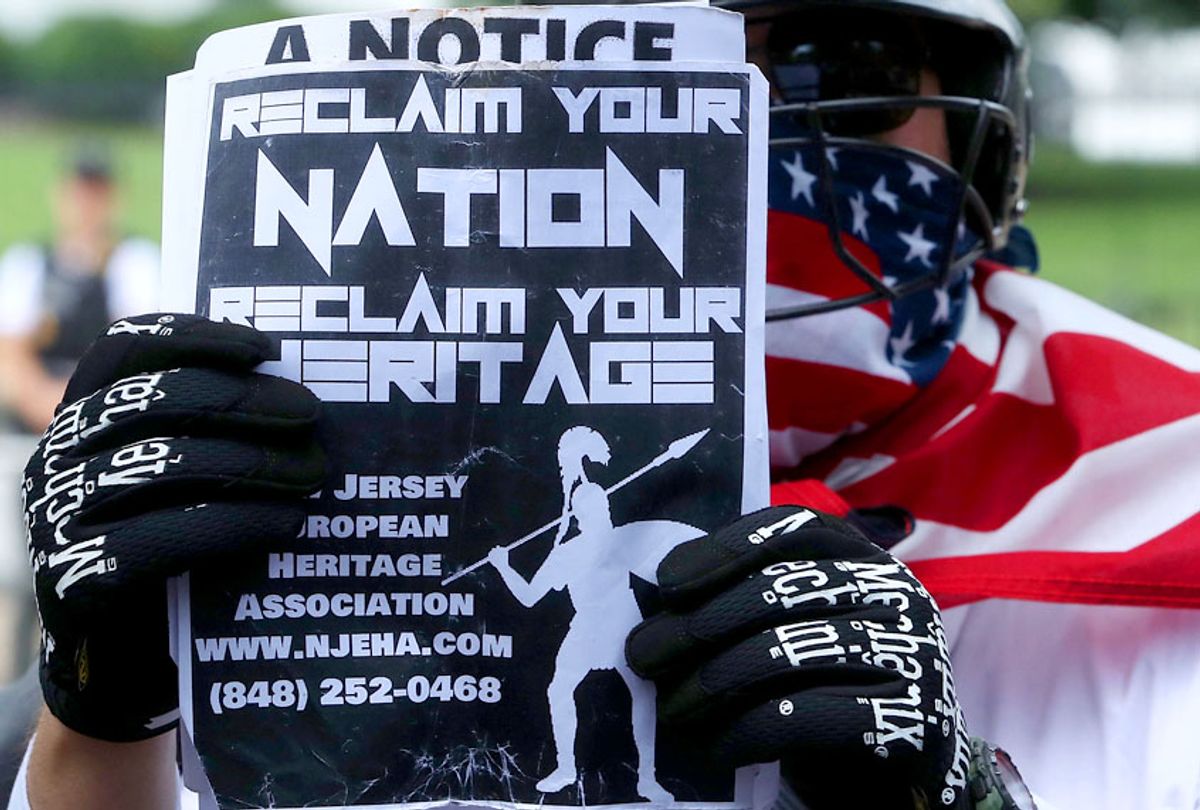

The counter-protestors had been organized by Black Lives Matter, the International Socialism Organization and Antifa (short for Anti-Fascist), a group of young men and women who, numbering in perhaps the hundreds, were dressed in dark scarves and jeans, their faces obscured by helmets and masks.

For the next 50 minutes Kessler and other participants delivered a series of convoluted speeches. “I’m going to talk about white civil rights,” he said. “But let me tell you about the day I’ve had.” He blamed law enforcement for making him show up too early. He speculated on the possible supporters who’d been left behind. “This rally is about standing up for the rights of white people,” he added at the end, “as white people become a minority in the United States and Europe by 2050.” Into the reporters’ recording devices he spoke with the halting lilt. “Two minutes,” he finally shouted, “we gotta go, it’s raining!” Under a silver umbrella he wrapped up his speech.“God Bless America,” he said. And then he ducked into a white van and was gone. Others followed. Behind a police escort, the Unite the Right 2 supporters disappeared in the distance.

By now the rain was coming down. Like a fine pale curtain it draped the D.C. metro area, drawing from the west. It was only 5 p.m.: a half-hour before the rally that had just concluded was supposed to start.

In the absence of the white nationalists, the thousands of counter-protestors grew restless. Eventually some of the Antifa members started throwing water bottles and eggs at police. Afterward, in the presence of a large group of journalists, they lit on fire and watched burn a Confederate flag. Finally, without much else to do, they dispersed.

This much was clear: Jason Kessler had failed in every discernible manner to pull off the sort of spectacle that thousands of people had gathered that afternoon in Washington, D.C., to oppose.

Not that this would affect in any way his interpretation of the events. “#UTR2 was a solid success,” Kessler tweeted afterward, adding: “I’ll have my HD footage of everything that went down online later.”

This weekend, as I stood in the crowd watching the Unite the Right 2 rally with the counter-protestors surrounding it, I was struck again by a question that’s been troubling me for the last two years: How do we best define the term fascism within our American political context?

In a 1944 op-ed for the New York Times, Vice President Henry A. Wallace described an “American Fascist” as a person “whose lust for money or power is combined with such an intensity of intolerance toward those of other races, parties, classes, religions, cultures, regions, or nations as to make him ruthless in his use of deceit or violence to attain his ends.”

Umberto Eco, an Italian writer who grew up in the 1930s, saw fascism as an inherently adaptable system: “Fascism had no quintessence. Fascism was a fuzzy totalitarianism, a collage of different philosophical and political ideas, a beehive of contradictions.”

And to quote George Orwell: “Almost any English person would accept ‘bully’ as a synonym for ‘Fascist.’ That is about as near to a definition as this much-abused word has come.”

But is it possible to apply this term accurately in 2018?

“Mussolini did not have any philosophy,” Eco explained in a 1995 essay. “He had only rhetoric.” Eco went on to enumerate fourteen traits by which we might recognize the trend of fascism in a post-war political system like that of the United States, including: a cult of tradition; action for action’s sake; fear of difference; appeal to a frustrated middle class; obsession with a plot; machismo, selective populism, and (quoting George Orwell), Newspeak: “All of the Nazi or Fascist schoolbooks made use of an impoverished vocabulary, and an elementary syntax, in order limit the instruments for complex and critical reasoning.”

In this context, when we talk about someone like Jason Kessler — about neo-Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan; about our country’s seemingly endless entanglement with white supremacy — perhaps the most apt definition of American fascism can be summed up by another of Eco’s traits: Contempt for the weak.

In the Italian incarnation of fascism, violence was the key means to obtaining power; inherent to the idea of taking autonomy from others was the perceived righteousness in one’s right to do so. Which is not to say that fascistic tendencies in the American system eschew this tool (far from it) but what makes fascism a unique and specifically insidious trend in our present day is its amorphous nature: the empty rhetorical fuzziness that, while lacking the ideological purity of Nazism or communism, instead denudes, through attrition, the health of our democratic norms, until the only thing left is what we might call the American brand — a promise of social and economic mobility, of progress on civil rights, of opportunity — that at the same time lacks those structural safeguards by which such ends were once achieved.

In other words, another way to define fascism in 2018 America is as the opposite of our participatory democracy: its stark daguerreotype, an occluded system of power that, under the false banner of weakened ideals (the Constitution, the Bill of Rights), encourages the engagement of it citizens solely as a means to identify, segregate and silence any and all forms of dissent.

Which brings us back to Jason Kessler’s dismal performance over the weekend: to completely fail at every single organizational aspect of planning and executing the Unite the Right 2 rally — and then claim, in the space of a few tweets, that the whole thing was in fact “a solid win for White Rights activists” — is to unburden yourself from the objective reality that America, however flawed, has relied upon in the post-war era as a final line of defense to protect the rights of its most at-risk individuals against white supremacy.

READ MORE: Are white people ready to bail on democracy? These researchers say the danger is real

Not that Kessler’s strategic unreality is in any way novel. Far from it. In a fascistic society, Eco explains, “individuals as individuals have no rights, and the People is conceived as a quality, a monolithic entity expressing the Common Will. Since no large quantity of human beings can have a common will, the Leader pretends to be their interpreter.”

This weekend, as a small contingent of white nationalists bore themselves to and from Lafayette Park in a sweaty procession, the White House’s current resident was hundreds of miles to the north in New Jersey, where, on the grounds of his country club, he greeted representatives of Bikers for Trump, another sub-group of American society that’s shown themselves more than willing to embrace our country’s most fascistic tendencies.

“Let’s hear those engines now!” the president shouted at the bikers.

“Four more years,” they chanted back at him. “USA!”

In response the president pointed out the members of the media covering the event, and the bikers, on cue, started jeering. “Tell the truth!” they shouted at the journalists.

Afterward Donald Trump took to Twitter. “Hundreds of Bikers for Trump just joined me at Bedminster,” he wrote. “Quite a scene—great people who truly love our Country!”

Shares