From the first accusations against Harvey Weinstein and the explosion of the #MeToo movement — which has ended or altered the careers of many powerful men in business, culture and politics — an unanswered question has hung in the air: What would happen when a prominent woman was accused of sexual harassment?

If your immediate reaction is that it’s not a fair or meaningful question, because such cases are so rare that they almost don’t exist, you have a point. It’s important to acknowledge that there is no remote semblance of parity or proportionality in this area. It’s not enough to say that 99 percent of sexual harassment complaints involve male perpetrators; a more accurate number might be closer to 99.9 percent.

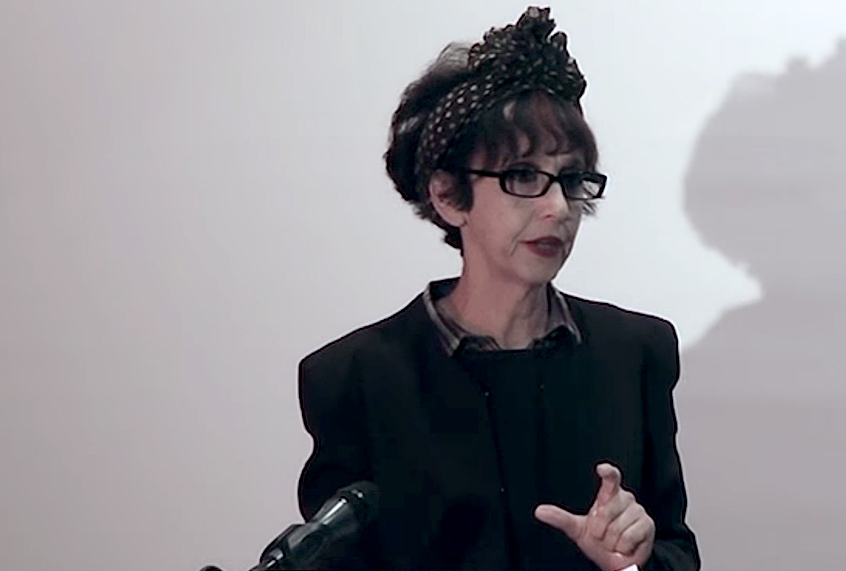

But improbable events happen all the time, as the universe constantly reminds us. This particular version of shark-bites-unicorn was bound to happen eventually, and to create a big stink when it did. But there’s another question beneath the surface in the case of Avital Ronell, the superstar academic philosopher recently suspended by New York University on charges that she sexually harassed a male graduate student over a three-year period. Can women commit sexual harassment? Or is sexual harassment by definition an instrument of patriarchal power, used exclusively by male authority figures to oppress, dominate and humiliate those beneath them?

It might sound like a stupid question. Indeed, from the legal point of view, or the point of view of classical liberalism, it is a stupid question: When one individual holds significant power over another, as is clearly the case between a graduate student and his dissertation adviser, certain interpersonal boundaries are not to be crossed and certain kinds of behavior are proscribed. The gender, sexual identity or sexual orientation of the people involved are irrelevant. That appears to be the playbook NYU followed in investigating and disciplining one of its biggest-name faculty members. Ronell will be on unpaid leave for the coming academic year and her future interactions with students must be supervised, which is surely a massive humiliation.

As Esther Wang observed in Jezebel this week, this whole business would likely have been swept under the faculty-lounge carpet if a philosophy blog hadn’t gotten hold of an unintentionally hilarious letter written in May and signed by numerous prominent academics, urging the NYU brass to go easy on Ronell. Nearly all the signatories were friends and colleagues of hers from the world of Continental-flavored academic philosophy, including feminist theory pioneer Judith Butler, postcolonial theorist Gayatri Spivak and Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek, the closest thing that field has to an actual celebrity.

While admitting that they knew next to nothing about the charges against Ronell, the letter-writers suggested she was the target of a “malicious campaign,” and hinted that her accuser, subsequently identified as 34-year-old Nimrod Reitman (now a visiting fellow at Harvard), had sinister motives. They praised her “brilliant scholarship” and “intellectual commitment” and asked “that she be accorded the dignity rightly deserved by someone of her international standing and reputation.” The letter concluded with a veiled threat that if Ronell were to face any significant punishment, “the injustice would be widely recognized and opposed.” (Note the passive voice and the lack of a clear subject: Opposed by whom? For a bunch of people who make their living with words, that was either sloppy or strategic.)

As Wang and everyone else who has written about l’affaire Ronell has noted, it all sounded way too much like the defensive arguments mounted to justify the abusive behavior of powerful men: They’re exceptional people, it was all a misunderstanding, genius can’t be asked to conform to social rules and anyway the accuser is untrustworthy. That glaring hypocrisy is the main reason why an otherwise minor academic scandal made the front page of the New York Times last week, in a feature story that offered lurid details of Reitman’s allegations against Ronell, including an episode when he says she “pulled him” into bed in her Paris apartment during a 2012 visit:

“She put my hands onto her breasts, and was pressing herself — her buttocks — onto my crotch,” he said. “She was kissing me, kissing my hands, kissing my torso.” That evening, a similar scene played out again, he said.

Ronell has denied that any such incidents occurred, and NYU’s investigation did not sustain Reitman’s allegations of sexual abuse and stalking, largely because there were no witnesses and no physical evidence. (A familiar outcome, let us note, for many women who make similar claims.) His claim of harassment was sustained, based on a lengthy pattern of emails in which Ronell addressed him with sexualized pet names like “baby love angel” or “cock-er spaniel,” or described her desire to kiss him or cuddle up together on her sofa.

Those details and others in the Times article led Judith Butler, a professor at UC Berkeley and perhaps the world’s most prominent gender studies scholar, to back away rapidly from virtually everything in the May letter to NYU, which she told the Chronicle of Higher Education “had been written in haste by a group of scholars” who were not “fully apprised of the facts of the case.”

“We ought not to have attributed motives to the complainant, even though some signatories had strong views on this matter,” Butler wrote. “And we should not have used language that implied that Ronell’s status and reputation earn her differential treatment of any kind.”

In other words: We shouldn’t have said any of the stuff we said, and the entire thing was an embarrassment. But I don’t think Butler would repent of the implied question I mentioned earlier: Whether it’s legitimate to prosecute a woman for sexual harassment under any circumstances. There’s no way to understand the contradictions of the Ronell case, or why it has set the small but intensely combative world of academic feminism and critical theory aflame, without acknowledging what the philosophy department might call the epistemological importance of that question.

Ronell’s defenders have not, to my knowledge, categorically claimed that she could not have sexually harassed or abused Reitman because she is a woman and he is a man. But they’ve come pretty close. One of Ronell’s NYU colleagues, the visiting German scholar Ilan Safit (who is male), told Jezebel: “It’s not the same thing to accuse a male person in power versus accusing a woman. It’s just not the same thing, because we’ve got a culture and a very long history in which males were dominant and abusing their power.”

That apparently straightforward and even naïve-sounding statement, I believe, points toward a core philosophical conflict. We can agree that that history of male dominance exists and that it’s still relatively rare for women to hold positions of power. Does that mean that law and justice must account for that in some proactive way? At the risk of oversimplifying a complicated argument, I’m pretty sure that some strands of the Franco-German philosophical tradition that produced Butler and Ronell and Žižek and numerous other intellectual heavyweights would contend that women cannot hold meaningful power over men, given extant cultural and historical circumstances, and that to punish any woman for an infraction against a man based on power relations is inherently unjust.

I don’t think I agree with that, which would come as no surprise to Judith Butler. On a practical level it doesn’t mesh well with the Anglo-Saxon legal convention of impartial justice delivered to all comers on equal terms. (Which European critical theory also perceives, by and large, as a system of social oppression.) But the notion of justice as an affirmative or restorative process devoted to correcting social ills, rather than an even-handed arbiter, is clearly neither frivolous nor unsophisticated, and has considerable intellectual firepower behind it.

In the first published version of this article, I proposed that notion of justice as the best way to decode University of Texas professor Diane Davis’ statement to the New York Times that the Ronell case represented a perversion of Title IX and the #MeToo movement, in which “this incredible energy for justice is twisted and turned against itself.”

In a subsequent email to Salon, Davis said that was not accurate. Times reporter Zoe Greenberg had portrayed her as a “caricatured feminist,” Davis wrote, adding that the full statement she had provided to the Times (as quoted in the Chronicle of Higher Education article) made clear Davis was “not suggesting that the problem is that a woman, a feminist, is being accused by a man. My concerns have to do with other issues involved in this specific case.” I asked Davis to elaborate on those other issues, and will add a further update if she replies.

In any event, I think it’s fair to conclude that the intra-feminist dispute over whether or not to defend Ronell — explored in both Wang’s Jezebel article and Katherine Mangan’s for the Chronicle of Higher Education — is at root a conflict between liberal and radical visions of justice. Perhaps because Ronell’s defenders know that their views are not widely accepted outside the academy, and have been unwilling to argue directly that no woman can ever be prosecuted as a harasser, all sorts of other irrelevant or semi-relevant issues have been dragged into the fray. (Ronell herself has not made that argument, and quite likely would not agree with it.) Sexual orientation has been proposed as a mitigating factor: Reitman is a gay man and Ronell identifies as a “queer woman,” and she has said that what he interpreted as inappropriate sexual come-ons were actually “florid and campy communications” rooted in their overlapping identities, or “hyperbolic gay dialect.”

Žižek has similarly suggested that Ronell’s “eccentricities” and deliberately provocative personal mannerisms posed a challenge that politically correct American academia couldn’t handle. (How well would that go over if he were defending himself, or any other man?) He appeared to refer to the various insinuations made against Reitman, almost always without naming him: Maybe Reitman is an uptight prude who refused to play along with Ronell’s whimsical role-playing, which was all part of her philosophical project. Maybe he’s a crypto-right-wing agent, out to destroy Title IX and the #MeToo movement and bring down a prominent feminist scholar. (While acquiring a philosophy Ph.D. in the process, which is really going to a lot of trouble.)

I’m not sure anyone has yet noticed the clues to this event in Ronell’s past, and in academic history more generally. To a large extent, what we see here are the effects of a cultural and generational shift that has left Ronell and many of her academic peers — long convinced that they were the hippest and most radical people in the known universe — behind. She came of age in the free-for-all, trans-Atlantic academic culture of the 1970s, and as someone who grew up on and around the Berkeley campus during that same period, I can assure you that the mythology is not all that exaggerated.

It’s well known that Ronell was a student and acolyte of Jacques Derrida, the biggest name in postwar French philosophy — and a notorious womanizer who would surely run afoul of #MeToo if he were teaching today. I can find no indication that she and Derrida were lovers, although that would surprise exactly nobody.

But their relationship takes on a different coloration in Benoît Peeters’ authoritative biography “Derrida,” which reports that Ronell began an affair with Derrida’s son Pierre while she was staying with the family for the Christmas holidays in 1979, when she was 27 and Pierre was 16. They moved in together the following year (after Pierre’s graduation from high school), living for a time in a Paris apartment borrowed from one of Derrida’s colleagues. Her relationship with Pierre, Ronell told Peeters, “was a way of becoming part of the family. … For me, those years in Paris correspond to a really lovely dream.”

That liaison may look slightly unsavory in the rear-view mirror, but it was not illegal and was only mildly unconventional at the time — the teenage boy’s love affair with an adult woman is a staple ingredient of French fiction. It reportedly made Derrida père pretty uncomfortable, which may have been the point. But I think we can agree that the whole thing would be deemed off limits today, whatever the genders of the people involved.

Perhaps we perceive a pattern, and not just about a predilection for younger guys: Someone who sleeps with her intellectual mentor’s child in order to gain entry to his family is confusing all kinds of boundaries between work, family life and romantic life, either deliberately or because she can’t help it. She is also making clear that she doesn’t notice or doesn’t care how the outside world perceives her.

One could speculate that Ronell learned early that sexual seduction of younger people could be a tool of power, or that she studied and emulated Derrida’s well-known tendencies, in especially confrontational fashion. In any case, it was a winning career move in late-‘70s Paris, which may be her problem in a nutshell. What played as bohemian daring when she was a young intellectual in that place and time has an entirely different resonance for a tenured professor in 21st-century America. Far more people than have ever read Ronell’s dense and challenging prose will now know her as a predatory perv.

Is there a profound sexist injustice in that? Absolutely. If Avital Ronell struck a blow for feminism, it may lie in the fact that she believed she was so awesome that the rules about how to behave with other human beings didn’t apply to her. It’s a widespread problem among my gender, but until very recently not among hers.