While it was pursued less emphatically in the movie than in the novel, there were continual hints that Deckard might be something other than human. What, for example, of the blade runner who meets his demise in the film’s opening scene? Is it a coincidence that he looks and sounds remarkably like Harrison Ford/Rick Deckard? Or are they the same model of blade runner? Isn’t it odd that the headquarters of the Tyrell Corporation and Deckard’s apartment (modeled on Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis-Brown House of 1923) are both inspired by Mayan architectural design? (Neumann, 1996) Why do Deckard’s eyes briefly glow with a red reflection? And how does Gaff know about Deckard’s unicorn reverie? Small wonder, then, that Deckard is edgy from the start, and that his anxiety so easily slides into paralysis and panic.

The Deckard debate is, in some ways, a denial of what the film really does offer, which is a double reading: undecidability. Noël Carroll has argued that "Citizen Kane" was designed to support two entirely contradictory interpretations of Rosebud’s importance to Charles Foster Kane. (Carroll, 1989) This is somewhat true of "Blade Runner" as well: Marvin Westmore, the film’s chief make-up artist, noted that "a lot of things we did on 'Blade Runner' were 'possibly it’s this' or 'possibly it’s that,'" in keeping with Scott’s desire to make a film that was more evocative than explicit. To some extent, though, Deckard’s status is undecidable because nobody finally decided. Some versions of the script made Deckard into an android, others don’t even raise the question. Scott wanted to include hints that Deckard was a replicant, but with all the changes and revisions, it’s no wonder that audiences were baffled.

But the, to my mind, obsessive desire to answer the question has always seemed misguided. If Deckard is a replicant, then what’s the moral of this story? The issue of human definition is clearly – to me – central to the work, and thus the ambiguity is crucial. Many of the clues to Deckard’s status could certainly be taken metaphorically. The unicorn, for example, could easily represent Rachael: it is, after all, an archetype. Murray Chapman’s FAQ reasonably links it to the unicorn symbolism in Tennessee Williams’s "The Glass Menagerie," and the girl who was "different to other horses." "Rachael is (and always will be) a replicant among humans, and will be different, like a unicorn among horses, because of her termination date." And when Rachael asks Deckard whether he has ever taken the Voight-Kampff test, she may not be asking about his literal human status, but about his capacity for the empathy that the machine measures.

On the other hand, for Slavoj Žižek, philosopher and cultural theorist, the most radical implications of "Blade Runner" depend upon Deckard’s standing revealed as a replicant. "Blade Runner," he argues, is valuable in that it stages a confrontation with our own "replicant-status." Žižek is writing through the discourse of Lacanian psychoanalysis, in which the self never belonged as fully to itself as Descartes’s cogito implied or as fully as we want it to (Deckard and Descartes are homophones, he notes, a pun for which I’d give Philip Dick full credit). "Our" replicant-status is not just a function of our constructedness (old news, really), but of the awareness of the void (the gap between "our" and "selves") that follows its recognition. It is the replicants’ obvious knowledge of their own manufacture that makes them our (or Žižek’s) "impossible fantasy-formation."

Even before the advent of what is known as "the society of the spectacle" the cogito was incomplete, but the exteriorization of memory in the information age makes that fundamental error all the more evident. Computer networks and satellite systems make the "decentered" or "virtual" self newly unavoidable, but they hardly invented it. Replicants expose the hubristic self-misconception of the human – the mythos of the self-sustaining "self" becomes all the more untenable. Žižek writes: "It is only when … I assume my replicant-status" that "I become a truly human subject." It is when we acknowledge our own replicant-status that we come face to face with ourselves as that irresolvable paradox: the "thing" that "thinks."

Žižek has criticized the Director’s Cut as inadequate and compromised regarding Deckard’s status. He wants Deckard to be unambiguously a replicant and to confront that reality: for him it is in that confrontation that the film’s meaning lies. But there is someone else at the film’s center who does confront his post-human condition – gleefully – and while Deckard/Descartes remains mired in agonized denial, Roy Batty (batty, nutty, kooky) is romping through the film, the "thing" that thinks and fights and pouts and plays and poses. More human than human, right? Batty provides a kind of antidote to Deckard’s panicky blandness. After killing Tyrell, Batty rides the elevator back down the side of the pyramid. In one of the film’s best subjective moments, he gazes heavenward in what Hampton Fancher points out is "the only shot in the whole movie where you see stars. And they’re moving away from him, as if he’s some kind of fallen angel."

READ MORE: The bizarro world of Steven Seagal: Hero in the movies, villain in real life

Roy is a perfect denizen of the modern city; he embodies its kaleidoscopic essence. The city, after all, is a masked ball, a place of emergence and submergence, opulent display and clandestine transformation. Criminals might benefit from the possibilities the concentrated city offered for anonymity, but they weren’t alone. "In retrospect it is clear that the laws of the costume ball have governed Manhattan’s architecture," Rem Koolhaas has claimed. "The costume ball is the one formal convention in which the desire for individuality and extreme originality does not endanger collective performance but is actually a condition for it."

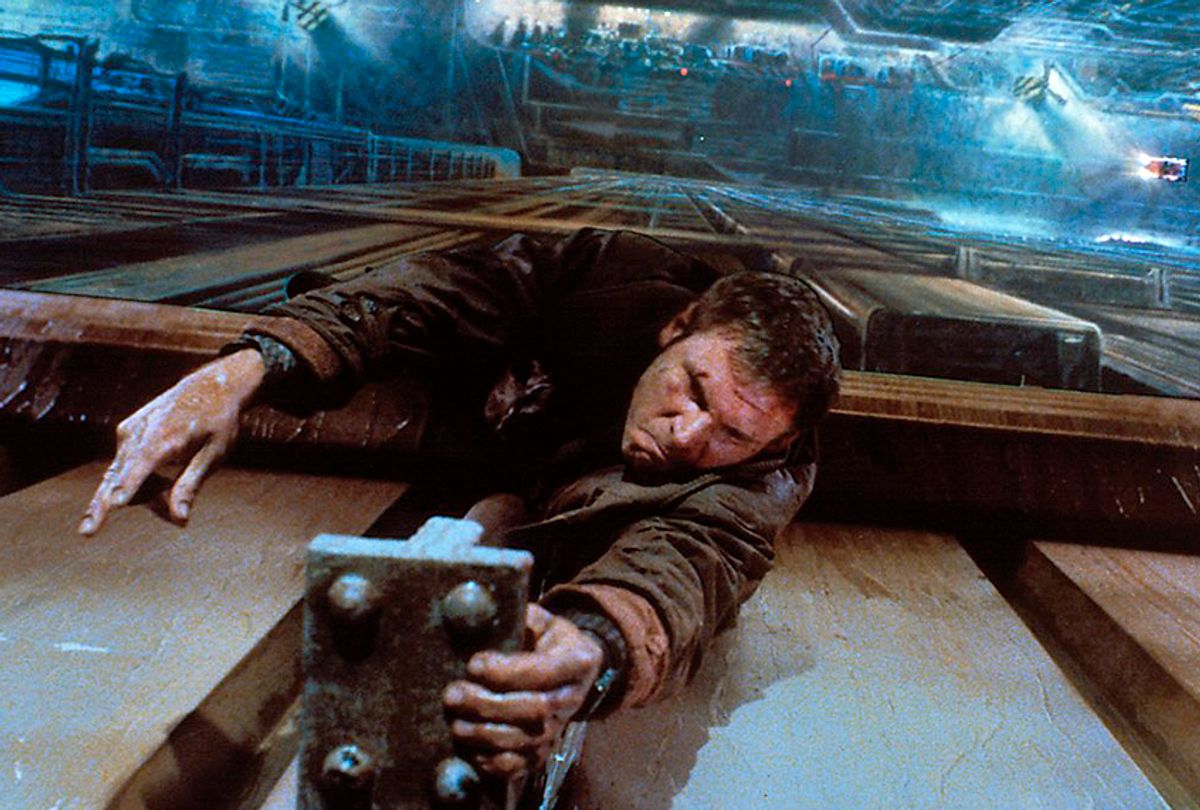

The protracted battle between Deckard and Roy extends from Sebastian’s home to other apartments in the near-abandoned Bradbury Building to the rooftops. Throughout this penultimate sequence there is a constant straining upward, a physicality reminiscent of the final showdown with the spider in "The Incredible Shrinking Man" (1957). There, too, the scenario forces the protagonist upwards in a straining gesture towards human triumph over an anti-human enemy: these are climbs towards transcendence. But "Blade Runner" will complicate these oppositions. Roy’s death was the last sequence to be filmed, and while the exhaustion on Harrison Ford’s face as he watches his "enemy" die is real enough, it is also the exhaustion of humanity on display.

Shares