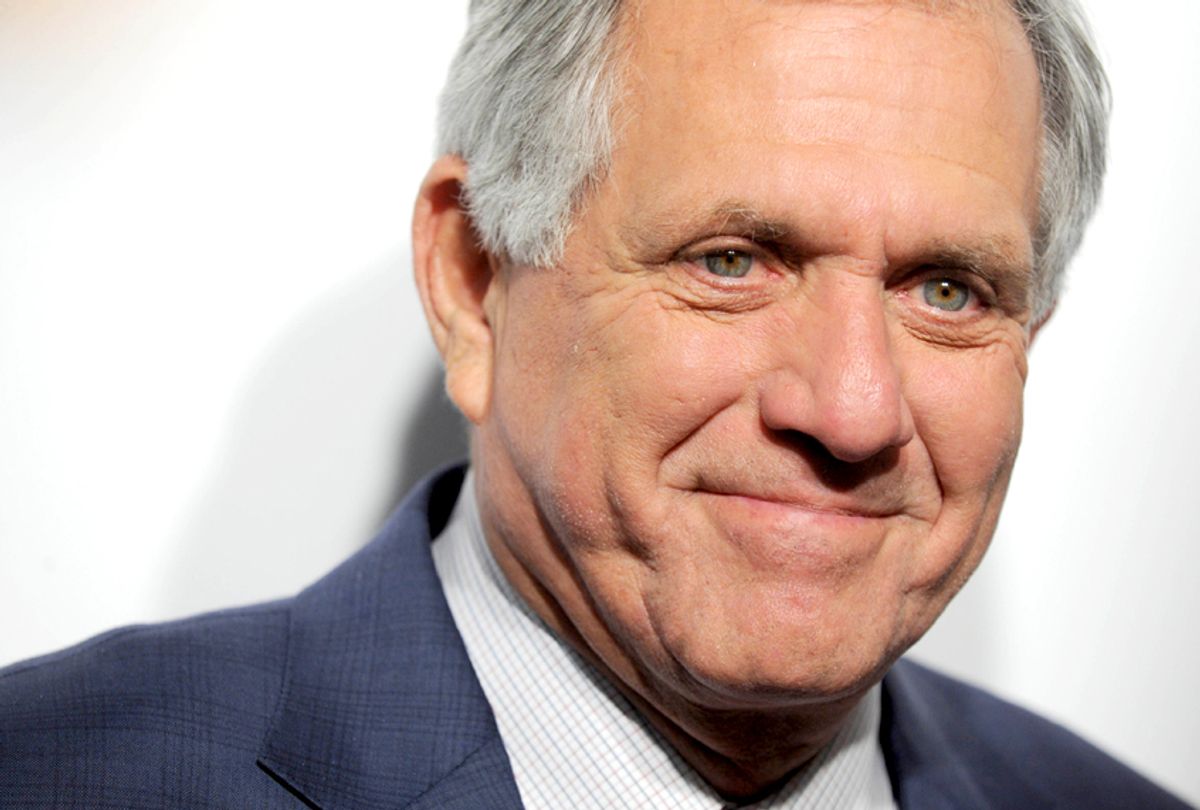

On Sept. 9, CBS Chairman Les Moonves resigned, following accusations by 12 women of harassment and assault.

His departure, however, has not followed the script of other executives publicly shamed over harassment allegations and thrown out onto the curb.

Unlike television hosts Matt Lauer or Charlie Rose, he kept his job for several weeks after The New Yorker published the first of two articles on his alleged transgressions, which contained accounts from six accusers. Lauer and Rose were fired within days.

Moonves was also able to negotiate an exit package with a number of face-saving provisions, including the opportunity to resign, a temporary non-disparagement clause, and confidentiality of the results of the CBS internal investigation currently underway.

He also retains the theoretical, if unlikely, possibility of receiving a portion of his more than US$180 million severance package, pending the outcome of that investigation.

Why was Moonves allowed to stick around and leave on his own terms, when so many others were unceremoniously dumped? CBS — which could have easily stuck to the script – isn’t saying.

But I have a different theory, based on the timing of the deal and the contracts involved, where Moonves was used as a shield in an unrelated power play. If true, it reveals how #MeToo has become more than just a movement in the corridors of corporate power.

Firing Moonves for "cause"

Back in July, when The New Yorker published its first story, the CBS board would have been within its rights to fire Moonves based on harassment allegations from two former CBS employees, as well as a job candidate he reportedly assaulted during a pitch meeting.

Under CBS’s employment contract with Moonves, the company could have fired Moonves for “cause” with no severance package or settlement. The definition of “cause” included a “willful and material violation of any company policy,” including the harassment policy.

As a former employment lawyer, I don’t think CBS’ lawyers would have had trouble finding language in the harassment policy to support a “cause” determination. Prohibited conduct includes “threaten(ing) or engag(ing) in retaliation after an overture or inappropriate conduct is rejected,” “a pattern of unwanted advances” and “unwanted touching.”

In other words, Moonves could have been fired summarily in July, just as CBS didn’t hesitate to end the career of one of his employees, Charlie Rose, back in November.

Given the taint surrounding men accused of this kind of behavior ever since #MeToo became a household word in October, why did CBS keep him around?

It’s possible directors on the CBS board didn’t consider the initial allegations sufficient to warrant termination. However, I would attribute their hesitation in part to an unrelated lawsuit – and their hope that Moonves could be a useful bargaining chip.

Moonves v. Redstone

For the last six months, CBS has been caught up in a lawsuit with its majority shareholder, National Amusements. That company is owned by 95-year-old business magnate Sumner Redstone and now run by his daughter Shari.

The lawsuit centers around a disagreement over the Redstones’ wish to merge CBS with Viacom, another company they own.

Moonves and the CBS board tried to thwart the Redstones by voting to dilute their powerful Class A shares, which give them control of the network. CBS basically proposed giving Class B investors the same voting rights.

This was like resolving a fight over the executive bathroom by giving keys to everyone at the company. Technically, you’re not taking anything away. Except that you’ve transformed it into a regular bathroom.

Both sides sued over this coup-by-dilution, and the trial was scheduled to start Oct. 3. As the parties engaged in settlement talks, the stakes were high. But it also gave Moonves some unexpected leverage.

Settling scores

Negotiation scholars note that bargaining power comes from your own ability to walk away from a deal. And your ability to make life painful for those on the other side of the table if they don’t agree to your terms.

CBS needed the pretense of keeping Moonves in order to negotiate a favorable settlement deal with the Redstones. Moonves was likely to be an important witness at trial. If CBS fired him before settling with the Redstones, he might not cooperate in court. That would erode CBS’ trial prospects and thus its bargaining position with Redstone.

At the same time, Moonves’ contract was also a pain point for the Redstones.

That’s because Moonves’ contract also had a provision known as a “golden parachute” clause. A golden parachute entitles an executive to a massive payout if certain changes are made to the company.

The golden parachute allowed Moonves to resign and receive a monstrous $182 million exit package – for a “good reason” resignation – if the Redstones wanted to change the composition of the board or force the company into a merger.

In other words, even if the Redstones won the lawsuit and kept their controlling stake, they wouldn’t be able to make big changes without enriching Moonves. This would be the pain — a controlling stake that can’t actually be wielded without awarding your adversary a mountain of cash.

So, I believe CBS sat on its hands while the trial date approached, refusing to exercise its right to terminate Moonves for cause.

The #MeToo movement presents a curveball

Moonves likely used this time to negotiate his own exit.

But the #MeToo movement wasn’t done. On Sept. 9, The New Yorker published fresh accusations against Moonves, and his options dwindled.

His settlement package mostly consists of CBS promising to do things it was willing to do anyway. Keep matters secret. Let the internal investigation run its course. Donate $20 million to the #MeToo movement to rebuild its reputation.

The high stakes game of chicken with Redstone also started to crumble. Redstone wanted Moonves out. And CBS really could no longer credibly say it wanted Moonves to stay.

Hours later, CBS announced both the settlement of the lawsuit and Moonves’ departure.

What it means

This isn’t the first time, and probably won’t be the last, that the #MeToo movement collided with other business interests — for better or for worse.

Harvey Weinstein’s victims may have decided to go public against him last year at least in part because his power in the industry was already on the decline. While #MeToo revelations fueled the leadership shakeup at Nike earlier this year, they apparently gained added force through an unrelated corporate power struggle.

Like any social movement that resides in the workplace, #MeToo can be attractive to competing business interests within an organization. For example, in the 1970s and 1980s, human resources departments capitalized on civil rights laws to cement their internal status and expertise, as sociologists Frank Dobbin and Lauren Edelman have documented.

For the #MeToo movement, the Moonves story is a partial victory, clouded by the board’s delay and his face-saving exit. But in a way, that’s okay. Business is messy. And the #MeToo movement is still very much at the table.

Elizabeth C. Tippett, Associate Professor, School of Law, University of Oregon

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Shares