In July, I was walking with my parents through the newly constructed Titletown District in Green Bay, Wisconsin, a new community development across the street from Lambeau Field, where the Green Bay Packers play their home games. It features a local brewpub, a boutique hotel, free outdoor games like foosball and shuffleboard and a large practice field, where kids can play football.

At one point, I heard my dad say, “I know who this is.” He had picked out the Packers’ president, Mark Murphy, hurriedly making his way through the swarming crowd of people. Murphy kindly paused to shake my father’s hand and then my mother’s and then my own.

As Murphy moved on, my dad’s next reaction was interesting to me as a political scientist.

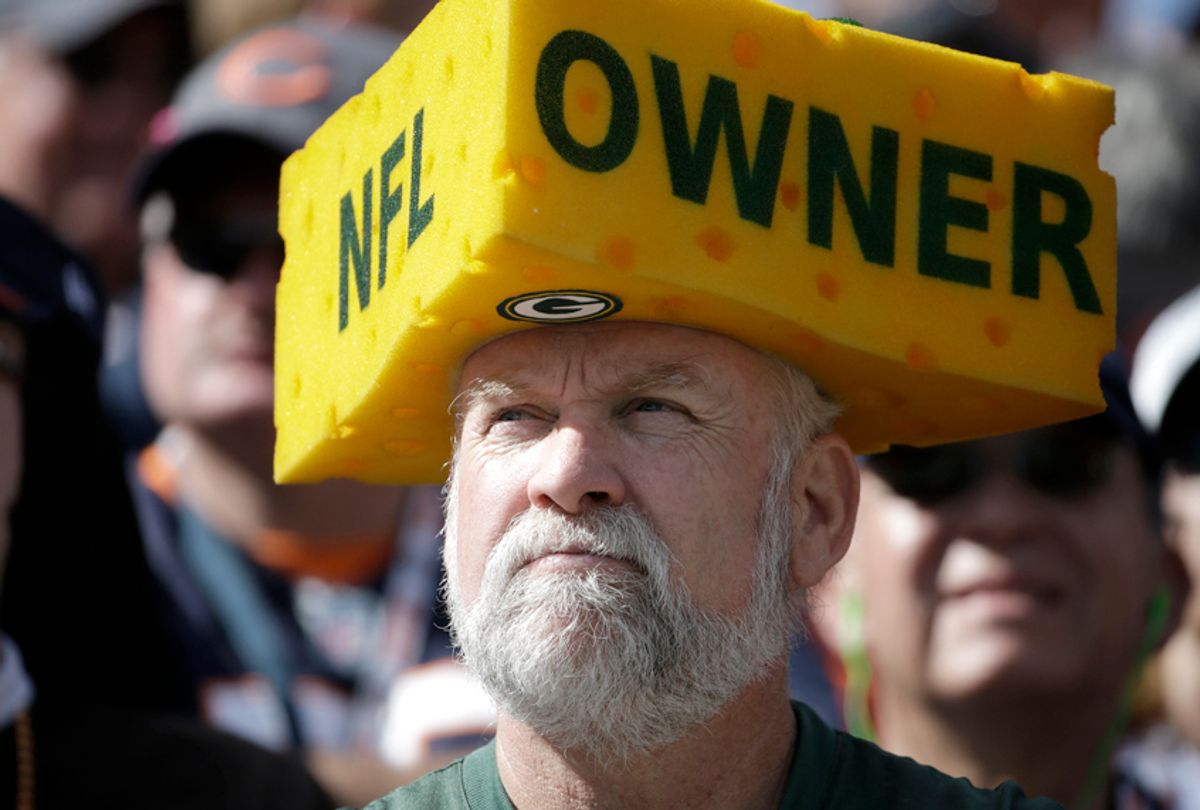

“The Packers are the only team with a president instead of an owner,” he said, turning to me. “You know, with every other team in the NFL, all that money the team makes, that goes straight to the owner.” Proudly, he continued, “The Packers don’t have an owner. All that money goes back to the community, the fans. It builds stuff like this,” motioning toward Titletown.

On our ride home, with Packer talk behind us, my dad started to ask me about my job prospects. I’m training to be a political theorist in an oversaturated job market with an overabundance of Ph.D.s, increasing university administration, increasing reliance on — ahem, exploitation of — adjunct instructors, and what feels like an all-time low in the diminution of the value of the humanities.

My job prospects are not good.

Next he asked why I decided on Immanuel Kant, the German philosopher, as my dissertation topic.

I explained that I had seriously considered Marx. But I didn’t choose him because I thought it would limit my job prospects further.

“Why?” My dad asked.

“Well, you know, because people often associate Marx with communism.”

“Communism – no, no, no,” he said. “I don’t want anything to do with communism. The very idea of it sickens me.”

In my head, I thought, “What an interesting cognitive dissonance.” Wasn’t the principle virtue of the Green Bay Packers based in a communist idea: collective ownership of the means of production? And because there is no owner, doesn’t that mean its proceeds go back into its community?

I’m not really interested in the degree to which the Packers are a communist organization. But I am interested in my father’s reaction to the word “communism,” and how this response conflicted with a real-world example of one of communism’s animating ideas.

He has not, to my knowledge, ever read Marx or any genuinely communist literature. But he has obviously adopted a negative attitude to the word.

Capitalist ideology seems to have launched a successful marketing campaign against communism. To be a communist, in my father’s mind, is to be against freedom. It is to want total control over the lives and fates of all individuals in society. It is to be a Stalinist.

What he fears isn’t communism; it’s totalitarianism.

I couldn’t bring myself to point this out. I couldn’t tell him, “Dad, everything you just said about the Packers – that’s communism.”

A special situation

On Aug. 18, 1923, the Packers became the first and only publicly owned team, selling $5,000 in shares to improve the team’s struggling finances.

Owning stock in the Packers is not like owning other stock, however. It pays no dividends. Although fans earn nothing financially by owning stock, this unique arrangement does ensure that profits don’t go into the pocket of one or a handful of owners. Profits go instead to Green Bay Packers, Inc. What fans gain — and not just those who own shares — is the assurance that their team will not leave Green Bay, the smallest market of all major American professional sports leagues.

In 1997, fresh off a Super Bowl win, the franchise turned again to its fans as “investors.” The team offered more fans the opportunity to join existing shareholders by selling additional shares. For $200 they could “own stock” in the team. Well aware of the fact that being an owner in this instance offers no real financial stake in the team, fans proudly purchased 120,000 shares.

In 2012, the team again expanded its sale of stock, selling an additional 30,000 shares. I remember my uncle excitedly showing me his share, framed and displayed prominently in his otherwise lightly adorned living room.

The Packers are not only unique in the NFL for being a fan-owned, nonprofit team, they are the only team the NFL will allow to be. The 1960 constitution of the NFL states, in what is known as the the Green Bay Rule, that “charitable organizations and/or corporations not organized for profit and not now a member of the league may not hold membership in the National Football League.” According to a member of the Packers’ board of directors, the model in Green Bay “is truly a special, special situation.”

Admittedly, the Packers organization still functions within capitalism. Although it lacks an owner, the team otherwise engages in all the same market-based exchanges as other teams. The Packers do show, however, how one communist principle might float within a capitalist sea. Without an owner, more people overall benefit. The team benefits first to be sure. But its interest happens to be the first interest of fans like my dad as well.

Sensing and seeing exploitation

My dad’s passion for the game is undeniable. My biased view is that it is unique, even among die-hards.

Otherwise, my dad is a rather typical Wisconsinite of his generation. He was born and raised in Sheboygan, where he still lives.

He grew up in an era when higher education was not the assumed post-graduation trajectory, so he became a laborer in a toilet seat factory.

I’m proud of him for that. I’m proud, particularly, because being a laborer is hard work. I know because I worked with him for two summers in college.

What makes it hard, for starters, is that the factory line always goes at the same pace. This means that if you have energy and would like to work quickly, you can’t. If you are feeling tired, sore or sluggish, you must keep up with the brisk, mechanical pace of the line. The job takes a physical toll.

I remember getting home from work one night and sitting down to watch a movie on the couch at 7:00 p.m. I woke up the next morning, still on the couch, leaving for work in the same clothes because I didn’t have time to change. I was 18. My dad has worked there 40 years and will continue to do so until he retires at 65.

As a laborer in a family-owned factory, my dad is well aware who profits when the company does: The family who owns it. Educated entirely on biographies of the American founders and iconic presidents, he has a surprising knack for seeing exploitation and inequality. I saw this in action when he went on about the benefits of the Packers not having an owner.

Like my father, my brother-in-law has a knack for seeing exploitation in action. In a recent diatribe, he railed against the popular view that professional athletes make too much money. According to the argument, athletes make extraordinary sums of money for playing a game, for doing something children do for free. That argument concludes that athletes ought to be paid less.

But my brother-in-law sees the big picture. Despite all the money they make, professional athletes are really making money for the owners — gobs of it.

Even though professional athletes make insane salaries by comparison to my father and my brother-in-law, they make far less than the owners. And this despite the fact that the owners themselves don’t do anything except own the team.

Without using any of the vocabulary — with no reference to bourgeois and proletariat, to owners of the means of production, and even without using the term “exploitation” — my brother-in-law has rather accurately described one of Marx’s main critiques of capitalism: Labor is fundamentally exploitative. Those who create surplus value are not the ones who benefit from it.

It doesn’t take Marx, apparently, to see what’s wrong with the owner-laborer, bourgeois-proletariat relation.

Refreshing an old idea with a new word?

When I teach Marx to my students, I ask them what comes to mind when they hear the name “Marx.” One of the first words listed is “communism,” but another is “Russia” or “the Soviet Union.”

Once we’ve assembled a list of associations, we begin to investigate how they came about.

I tell them that if you go to the Museum in the Round Corner, a former German Democratic Republic government office in East Germany’s lovely Leipzig, you’ll find a photo of a rally.

In a massive stadium, thousands of citizens each hold up a unique placard. Collectively each picture forms one gigantic image that can be seen from above. Organized by the communist government, the image is a blown-up portrait of Karl Marx with the phrase “Wir ehren Marx” — “We honor Marx.”

This display is an example of how the U.S.S.R. worked to make it look like it operated on Marxist principles. But communists such as C.L.R. James did not view Russia under Stalin as a true communist government. Nor did other scholars, like Hannah Arendt, who instead characterize Stalinist Russia as totalitarianism. It’s important to remember that Marx did not advocate totalitarian government. My Dad, however, associates communism with Stalinist Russia – and thus associates it with totalitarianism.

So much the worse for Marx.

If my father could dissect the vampirism of football franchise owners, if my brother-in-law could analyze the fundamentally exploitative structure of labor without him, is the biggest source of people’s attitudes toward communism the word itself?

If “communism” is too laden with historical failures and semantic difficulties, are “socialism” or “social democracy” better alternatives?

They, too, seem to register similar anxieties in society.

Although Bernie Sanders openly adopts the monikers, “socialist” and “Democratic socialist” as a member of the Democratic Party – as do ascendant figures in the party like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez – such politics continue to be maligned.

Attitudes are beginning to change. A recent Gallup poll shows that 57 percent of democratic-leaning poll-takers view socialism favorably. A deeper look at the demographics is revealing, however. Although attitudes to socialism are becoming more favorable overall, it is quite clear that the working class of my father’s generation are among the slowest to come around.

Of my father’s age group — 50 to 64 — only 30 percent viewed it favorably.

Perhaps an entirely new word needs to be coined. Hell, why not call it Packerism?

If you want a political movement to work in Wisconsin, that’s what to call it. But of course, what might be a successful rebrand in Wisconsin is not likely to be successful across the country as a whole.

So if not by calling it Packerism, how can the left renew an old idea with a new word?

Alan J. Kellner, PhD Candidate in Political Science, Northwestern University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Shares