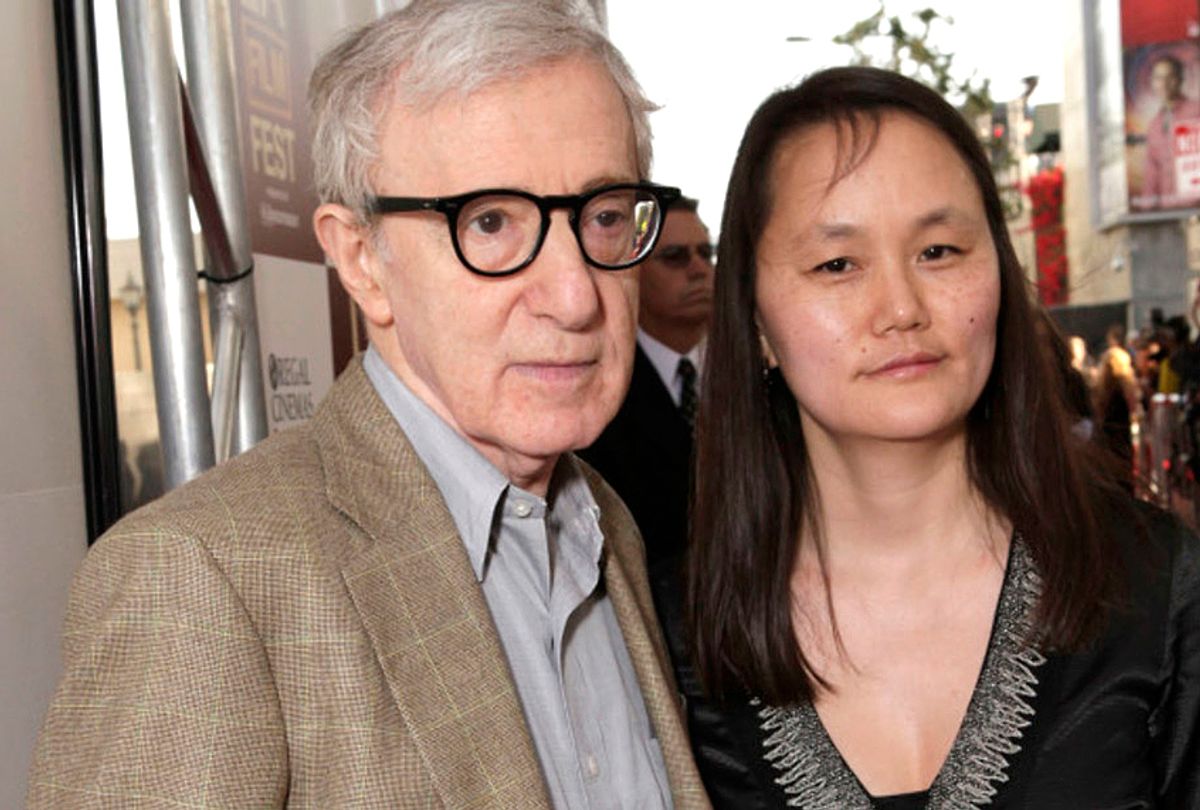

Over a weekend that felt like five years in internet time, after the online publication of two self-pitying essays penned by media celebrities who lost their jobs after allegations of sexual harassment and assault, and on the same day the woman who says Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh held her down and tried to rip her clothes off when they were in high school spoke out in the Washington Post, Vulture managed to pull off an even more unexpected story. That would have been a profile of Soon-Yi Previn, press-shy wife of Woody Allen and adopted daughter of his ex-partner Mia Farrow.

In the grand scheme of a truly epic weekend for women vs. the people who think all the hysteria about men’s abuses of power has gone too far, the Previn profile was hardly the biggest bombshell. But it is a quietly instructive example of an attempt to nudge the conversation about power and gender back toward the status quo.

Written by Daphne Merkin, who describes herself as “friends with Allen for over four decades,” the profile is in part a titillating bit of celebrity access into the somewhat boring Upper East Side home life of the once tabloid-notorious couple, knick-knacks, lasagna and all. But Merkin recently made media waves for rolling her eyes at #MeToo in a New York Times op-ed back in January, which, coupled with the disclosure about her long friendship with Allen, all but guaranteed that the cynical economy of outrage clicks would do its job.

It’s apparent from the beginning why Previn wanted her husband’s friend to tell her story. Previn says that Farrow has exploited the #MeToo movement by “parading” daughter Dylan’s allegations of sexual abuse against Allen (who has always denied those allegations), which finally prompted Previn to want to talk openly about her childhood with Farrow, which she alleges was marked by physical and emotional abuse and neglect.

“Once, she was seen as a victim, her youth and relative innocence taken advantage of by a powerful, much older man who sucked her into his vortex,” Merkin begins dramatically. “Or, alternately, she was a Lolita, a seductress who wittingly betrayed the Mother Teresa–like figure who’d saved her from life in an orphanage.”

(Lolita is an odd name to invoke in the lede of a profile of a man accused of child molestation by his own daughter, but the writer’s heart wants what it wants, I suppose.)

Merkin’s profile would like to posit that Previn was neither a naïf under Allen’s worldly spell nor a walking psychosexual nightmare who stole her mother’s man, but rather that Farrow practically drove Previn and Allen into each other’s arms, and hey, maybe Allen was even the innocent party in all of this, did you ever think of that? If that second part at least seems tough to swallow, there’s good reason.

She writes:

Knowing Allen over the years, as I have, I’ve come to understand that, despite his artistic gifts and endless years of psychoanalysis, there is something oblivious about him.

When Allen tries to explain himself, she turns to me as if he weren’t in the room: “He’s a poor, pathetic thing. He’s so naïve and trusting, he was probably putty in her hands. One thinks that he’s so brilliant … and yet on certain things he’s so shockingly naïve it makes your head spin and you think he’s putting it on. Mia was waaay over his head,” she says, and bursts out laughing — not quite at Allen but at the thought of his susceptibility to Farrow’s charms.

To Merkin, Allen simply declared himself, with characteristic, overly dramatic self-deprecation, “a pariah,” because “[p]eople think that I was Soon-Yi’s father, that I raped and married my underaged, retarded daughter.”

Demeaning language about disabled people aside, two things can be true here at once. Given the timeline of their relationship as they tell it, and the facts of their family ties, Allen was a perfectly law-abiding suitor to Soon-Yi. It can also be true that he occupied a slippery enough space in her life — while not a father figure, weirdly adjacent to a male authority figure as the father of her siblings and partner of her mother — for their romance to have been something of a nuclear option, and one that people would then judge as having been built on an inherent imbalance of power.

More things that can be true at once: Allen and Previn can be in a marriage that makes them happy, and the very facts of their marriage can make Allen seem shady and untrustworthy, especially to the younger generation who didn’t grow up revering his films and who likely first learned about Dylan’s abuse allegations in 2014 when she published them in the New York Times. That history may also make their marriage a source — if, as they most certainly believe, unjustly — of some measure of personal unhappiness as well.

READ MORE: Generation X’s kids have no idols, and that’s a good thing

So it is significant that Merkin’s profile allows Previn and Allen to push back at the idea of their marriage as an unsettling daddy-daughter analog — which has contributed to some level of ambient suspicion of Allen throughout the years — painting them instead as just another dullsville married couple whose 35-year age difference has collapsed over the decades into a comfortable and affectionate routine of “parallel play.” This is a new development — Allen has pushed a sideways version of that narrative himself over the years, going out of his way to characterize himself as benefiting from playing a “paternal” role to his much-younger wife.

Here he is in a 2005 interview with Vanity Fair:

“If somebody told me when I was younger, ‘You’re going to wind up married to a girl 35 years younger than you and a Korean, not in show business, not having any real interest in show business,’ I would have said, ‘You’re completely crazy.’ Because all the women that I went out with were basically my age. Two years younger. Ten years was the maximum. Now, here, it just works like magic. The very inequality of me being older and much more accomplished, much more experienced, takes away any real meaningful conflict. So when there’s disagreement, it’s never an adversarial thing. I don’t ever feel that I’m with a hostile or threatening person. It’s got a more paternal feeling to it.”

Ten years later, in an NPR interview in 2015:

I've been married now for 20 years, and it's been good. I think that was probably the odd factor that I'm so much older than the girl I married. I'm 35 years older, and somehow, through no fault of mine or hers, the dynamic worked. I was paternal. She responded to someone paternal. I liked her youth and energy. She deferred to me, and I was happy to give her an enormous amount of decision-making just as a gift and let her take charge of so many things. She flourished. It was just a good-luck thing.

At one point, Merkin wants to address this, but the couple distances themselves from the notion that Allen was ever “paternal” toward Soon-Yi:

Inspired by Alexis Clarbour, who told me her friend has “blossomed” in the years she’s been married to Allen, I ask Soon-Yi whether she thinks she’s been reshaped by her husband. “Reshaped?” she asks. “I mean, he’s given me a whole world, a whole world that I wouldn’t have had access to. So if you mean that way, then yes.” Allen joins in, in case I’ve gotten the wrong impression: “She’s got a large personality. I provided her with material access and opportunity, but it’s all her. I’m more introverted and nondescript.”

Why does it matter after all this time, now that Previn has been in a relationship with Allen for more than half her life and the shock of their affair has faded somewhat into tabloid history? Previn allowed Merkin to interview her out of a desire to defend Allen against what Previn characterizes as Mia Farrow’s public campaign against Allen’s reputation, in which Farrow has used the sexual abuse allegations Dylan maintains to this day as a weapon in the court of public opinion:

“I was never interested in writing a Mommie Dearest, getting even with Mia — none of that,” Soon-Yi tells me quietly but firmly. “But what’s happened to Woody is so upsetting, so unjust. [Mia] has taken advantage of the #MeToo movement and paraded Dylan as a victim. And a whole new generation is hearing about it when they shouldn’t.”

And Previn also decided to defend Allen because he’s no good at it himself:

His unwillingness, or perhaps inability, to contest his ongoing vilification — or, when he does take it on, to fan the flames (“I should be the poster boy for the #MeToo movement,” he recently told Argentine TV. “I’ve worked with hundreds of actresses, and not a single one — big ones, famous ones, ones starting out — have ever, ever suggested any kind of impropriety at all”) — also contributed to Soon-Yi’s decision to talk publicly.

For a woman keen throughout the profile to assert her own agency in the affair with Allen that began when she was 21, when he was still her mother’s partner, Previn seems surprisingly willing to downplay Dylan’s agency in advocating for herself as an alleged victim of sexual abuse.

Previn seems to place the blame for Allen’s career circling the drain — as his audience, inside Hollywood and out, has lost its taste for separating the art from the creator’s personal life — squarely on Mia Farrow, whom she also accuses of a number of abusive and neglectful behaviors, disturbing patterns which are corroborated by some of her siblings and also disputed by others.

(Again, many things can be true here at once: Farrow’s many children can have had widely different and conflicting experiences, tragic or nurturing or somewhere in between, which may never reconcile into a comprehensive picture of what it means to be Mia Farrow’s child.)

The emphasis on Mia Farrow as the source of Allen’s diminished social and professional prospects is odd at first read. It’s obvious to anyone paying attention over the last four years that his “pariah” status really began with a groundswell of people believing adult Dylan’s allegations, not fallout from a decades-old ugly breakup. But casting Dylan’s allegations as Mia’s machinations allows the story to shift, from a woman saying she was sexually abused by her father to a more comfortable narrative, culturally speaking: I told you my ex was crazy.

How Allen characterizes his relationship to Previn matters for the same reason that Previn’s characterization of Farrow as a cruelly abusive and vindictive head-case matters — credibility is what wins and loses public reputation wars, and Previn and Allen likely see Mia's credibility as easier to shake than Dylan’s.

And if, along the way, they can recast Allen as “elderly dorky husband” rather than some dirty old man “obsessed with teenage girls” — as the headline on a story by Richard Morgan, who pored over 56 boxes of Allen’s papers archived at Princeton, claimed in the Washington Post — so much the better. Because those papers reveal quite a through-line:

Allen's work is flatly boorish. Running through all of the boxes is an insistent, vivid obsession with young women and girls: There's the "wealthy, educated, respected" male character in one short story ("By Destiny Denied: Incident at Entwhistle's") who lives with a 21-year-old "Indian" woman. First, Allen's revisions reduce her to 18, then double down, literally, and turn her into two 18-year-olds. There's the 16-year-old in an unmade television pitch described as "a flashy sexy blonde in a flaming red low cut evening gown with a long slit up the side." There's the 17-year-old girl in another short story, "Consider Kaplan," whose 53-year-old neighbor falls in love with her as the two share a silent, one-floor-long elevator ride in their Park Avenue co-op. There's the female college student in "Rainy Day" who "should not be 20 or 21, sounds more like 18 — or even 17 — but 18 seems better." That script includes a male college student but gives no description of his age. Another of Allen's male characters, in a draft of a 1977 New Yorker story called "The Kugelmass Episode," is a 45-year-old fascinated by "coeds" at City College of New York. In the margin next to this character's dialogue, Allen wrote, then crossed out, "c'est moi" — it's me.

Allen’s fiction might be full of May-September (October, November) romances, the recast narrative can go, but that's just story. In real life, his defenders can emphasize, he's always been different.

Has he, though? Back in March 2015, which feels like an entire lifetime ago, I wrote about Woody Allen and Mariel Hemingway and “Manhattan” and the strange blind spots we can have about men, art and power. This was before Allen was “canceled”; despite Dylan bringing her allegations of childhood sexual abuse back into the conversation in a 2014 “open letter” in the New York Times, we were still struggling to have a conversation about how to separate a problematic man from his art and vice versa, because in our patriarchal culture of celebrity one has always protected the status of the other.

In her memoir, Mariel Hemingway detailed her role as Allen’s teenage love interest Tracy in his 1979 film “Manhattan,” and explained how Allen’s romantic attentions to her did not stop after the cameras stopped rolling. The scene she paints does not exactly paint Allen as, to use his words, “the poster child for #MeToo.” As I wrote in 2015:

She says she knew he had a crush on her, but she dismissed it as “the kind of thing that seemed to happen any time middle-aged men got around young women,” because we have groomed our young women to expect this kind of attention, and to tolerate it, even. When he arrived at her parents’ home and tried to convince her — still just 18 at the time — to come to Paris with him on what was clearly going to be a lovers’ vacation, even her parents encouraged her to go. At 18, she was charged with being the sole level-headed adult in the room: Ascertaining that she would not have her own hotel room on this Paris trip, that he expected they would travel together, she put the brakes on the entire plan. “I wanted them to put their foot down,” she writes. “They didn’t. They kept lightly encouraging me.”

Hemingway was left to find her own strength, waking in the middle of the night “with the certain knowledge that I was an idiot. No one was going to get their own room. His plan, such as it was, involved being with me.”

What a poor, pathetic thing Allen is in this story! He’s so naïve and trusting here; Mariel Hemingway, who had “never really made out with anyone” before Allen wrote a make-out scene for them in “Manhattan,” during which she says he “attacked me like I was a linebacker” — was waaay over his head, right?

There are so many threads to this story, and so many ways for a discussion of it to go wrong. But it's not a fascinating story because famous people let us peek inside their knickknack room. It's a story worth reading and contextualizing because it is trying to put Allen's story back under his control.

Merkin, in acknowledging how unknowable the private experiences within a family can ultimately be to outsiders, arrives at this insight: “All of life is filled with competing narratives, and the burden of interpretation is ultimately on the listener and his or her subjectively arrived-at sense of the truth.”

The competing narratives in this family are many, and they echo so many competing narratives out there in the world now about men, girls, women, sex and power. Soon-Yi Previn could have entered into a romantic relationship with her mother’s partner of her own free adult will and stayed in it for her own pleasure and satisfaction for decades, and Woody Allen could have benefited from an imbalance of power inherent in their relationship. Mia Farrow could have been a terrible mother or a wonderful mother, depending on which child you ask. Their breakup could have been vindictive and ugly and Dylan Farrow could be telling the truth. Woody Allen could have been thunderstruck by his relationship with a much-younger Soon-Yi and he could have tried to groom Mariel Hemingway to become his girlfriend as soon as she turned 18. None of these things necessarily cancel out the other, nor do they cancel out the truth that both women can have agency in their respective relationships with Allen. Soon-Yi Previn can have her reasons for being all in, and Dylan Farrow can have her reasons for wanting out.

Shares