One hundred years ago, the U.S. government published documents that fueled the mounting Red Scare, helped justify the American military invasion of Russia and poisoned American-Russian relations for years to come.

Newspapers across the United States began to publish the fake papers on Sept. 15, 1918.

Unbeknownst to the government, the documents were forgeries. They were created by Russian political interests whose party affiliation remains obscure, but whose objectives were clear. The documents were part of a Russian disinformation campaign — a common propaganda tactic during World War I — to discredit the Bolsheviks, who had just seized power in Russia after leading a Marxist revolution.

The publication of the documents was a classic case of the American government accepting bogus information because it confirmed its preconceptions and justified actions it wished to take.

We are scholars who work at the intersection of media and politics. We believe the incident illustrates the base power of disinformation lies not in technology, which many blame for the rise of counterfeit information today, but in weakness in human nature. The desire to confirm their beliefs about the Bolsheviks led top U.S. leaders to ignore credible and persistent warnings of the documents’ inaccuracy and aggressively assert government authority to discredit those few who questioned them.

The Sisson documents

By 1918, World War I had raged on for nearly four years, and the Russians, who fought on the side of the U.S. and others against Germany, had experienced two recent revolutions.

The first revolution ousted the Czarist regime. The second, led by Bolshevik leaders Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, ousted the provisional government.

Despite the chaos, the U.S. and Allies desperately needed Russia to continue fighting. But the Bolsheviks were intent on taking an exhausted Russian military out of the war and promised to begin peace talks with Germany once in power.

The Committee on Public Information, which operated as an American propaganda ministry during the war, sent Edgar Sisson, a former muckraking journalist, to Petrograd in November 1917, before the Bolsheviks seized power. He was to use publicity tools, which included press releases, films and speeches, to urge Russians to remain in the war.

By the time he arrived, the Bolsheviks were in power. A month later, they began peace negotiations with Germany.

The peace talks played into widespread rumors in Russia and elsewhere that Lenin and Trotsky were paid German agents. Before its ouster, the Russian provisional government tried to use the rumors to discredit the Bolsheviks and hasten their demise. But the rumors had never been proven.

This all seemed to change, however, in February 1918.

Raymond Robins, head of the American Red Cross Commission in Russia, gave Sisson confidential documents that implied Germans financed and directed the Bolsheviks. Sisson deemed the documents valid despite Robins’ doubts.

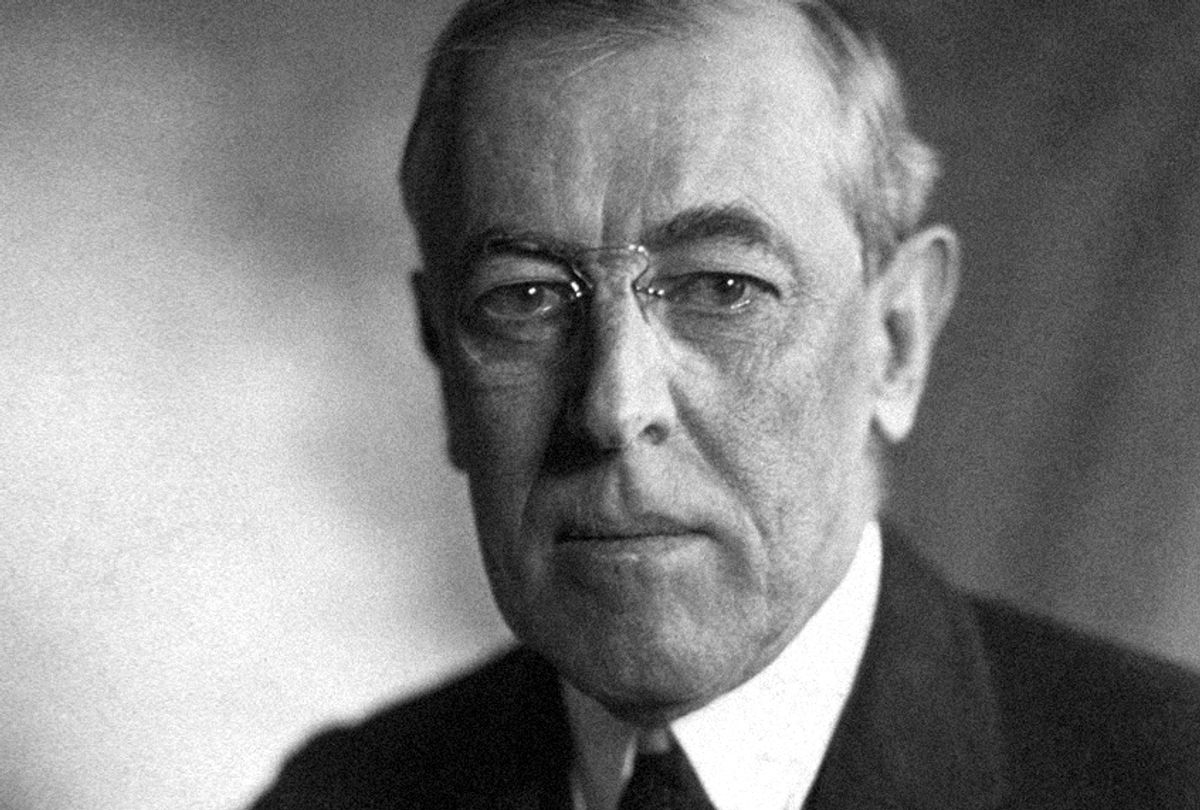

President Woodrow Wilson and the State Department encouraged Sisson to collect evidence that Lenin and his comrades were German pawns, which would support the administration’s anti-Bolshevik policies.

By the time he left Russia in March, Sisson had collected 68 documents, mostly with the help of a shadowy figure, Evgeni Petrovich Semenov. Semenov, a former secret service agent in the provisional government, told Sisson he lifted the papers from Bolshevik headquarters.

Documents make news in the U.S.

American press coverage of Sisson’s story was sensational. Most stories appeared on the front page and were published in installments during the week. They accepted the government view of Bolshevik treachery.

The government’s timing of the release was politically strategic. Wilson had by this time agreed to an Allied military intervention in Russia for the purpose of protecting stockpiles of Allied war material and ensuring the safe travel of anti-German forces through Siberia to the Eastern Front.

In August and September, U.S. troops were arriving in Russia. This move constituted a threat to the Bolshevik government and violated Wilson’s promise of self-determination.

But the fake documents legitimized intervention by suggesting that the Bolshevik stooges were not representative of the Russian people.

Compliant journalists

The documents presented a problem that often arises in national security reporting.

With little time or expertise to properly determine an account’s authenticity, journalists often rely solely on the government’s word. When a majority of the public is mentally prepared to accept the government’s account because it conforms to their preconceptions, the government can easily beat back doubts by calling doubters disloyal and un-American.

In a reasoned analysis of the documents published in a pamphlet by the Liberator, left-wing journalist John Reed showed they were probably forgeries and said they falsely justified military intervention in Russia.

George Creel, the head of the Committee on Public Information, sought to discredit Reed by labeling him the “center of the Bolsheviki movement in this country.”

Mostly, though, Creel evoked government authority as the chief basis for accepting the validity of the documents when they were questioned. This was the case with the lone establishment newspaper that challenged the authenticity of the documents, the New York Evening Post.

In letters found at the National Archives, Creel said the Post gave “aid and comfort to the enemies of the United States.” He expressed surprise that the New York Evening Post refused to accept evidence put forth by the government. And he told the paper’s owner that his editor had acted as an advocate of Lenin and Trotsky. He said the paper behaved as if it, too, had taken German money.

The New York Evening Post, he complained bitterly, was demanding “the Government should take the witness stand.”

The credulous acceptance of the documents by the press can be traced to the effectiveness of extensive wartime propaganda by the Committee on Public Information, which we have been studying for the past several years. One of the committee’s chief propaganda messages was widespread German spying and treachery in the United States and abroad.

It was an easy step, when nudged by the government, to believe the Germans enlisted godless Bolsheviks in their cause.

As the Literary Digest magazine observed, editors found “great satisfaction in adding legal proof to their moral certainty, and when the Government guarantees the authenticity of the documents proving that Lenin and Trotzky are German agents, it gives them an opportunity to speak their minds without hesitation and without reserve.”

Congress, too, was willing to endorse this view. The Democratic majority in the Senate used a special subcommittee to emphasize Bolshevik-German ties. They found witnesses who testified the Bolsheviki movement was a branch of the German government.

Power in plausibility

George Kennan and other historians have concluded the Sisson documents are “unquestionable forgeries,” but this does not mean they were devoid of truth.

As with all effective disinformation, their power lay in their plausibility. The documents’ authors enhanced their forgeries with facts. Germans did help the Bolsheviks, funneling millions of Deutsche marks to them during the war.

But, as one diplomat noted, the Bolsheviks would have accepted money from anyone. More important, the Bolsheviks sought to foment a communist revolution in Germany as soon as they could.

For those who spread disinformation, then, it is often not a matter of being tricked into believing the information they have spread. Creel, Sisson and others recklessly ignored warnings the documents were false. They wanted to believe the conspiracy, so they did.

Today, we call this confirmation bias.

The United States’ path to war with Iraq in 2003 eerily recalled that element of the Sisson documents. To make the case for an invasion, the George W. Bush administration relied heavily on Ahmadi Chalabi, an exiled Iraqi politician, and fellow Iraqi dissidents who wanted Saddam Hussein ousted.

Chalabi lined up a parade of Iraq defectors to provide compelling – and inaccurate – stories of Hussein’s terrorist connections and his stockpile of weapons of mass destruction. In addition to selling the invasion to the public, the campaign solidified the administration’s conviction that it was right to do what it wanted to do.

“It’s dangerous,” Chalabi was known to say from time to time, “if you believe your own propaganda.”

John Maxwell Hamilton, Global Scholar at Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, DC and Hopkins P Breazeale Professor, Manship School of Mass Communications, Louisiana State University and Meghan Menard McCune, Ph.D. candidate, Manship School of Mass Communication, Louisiana State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shares