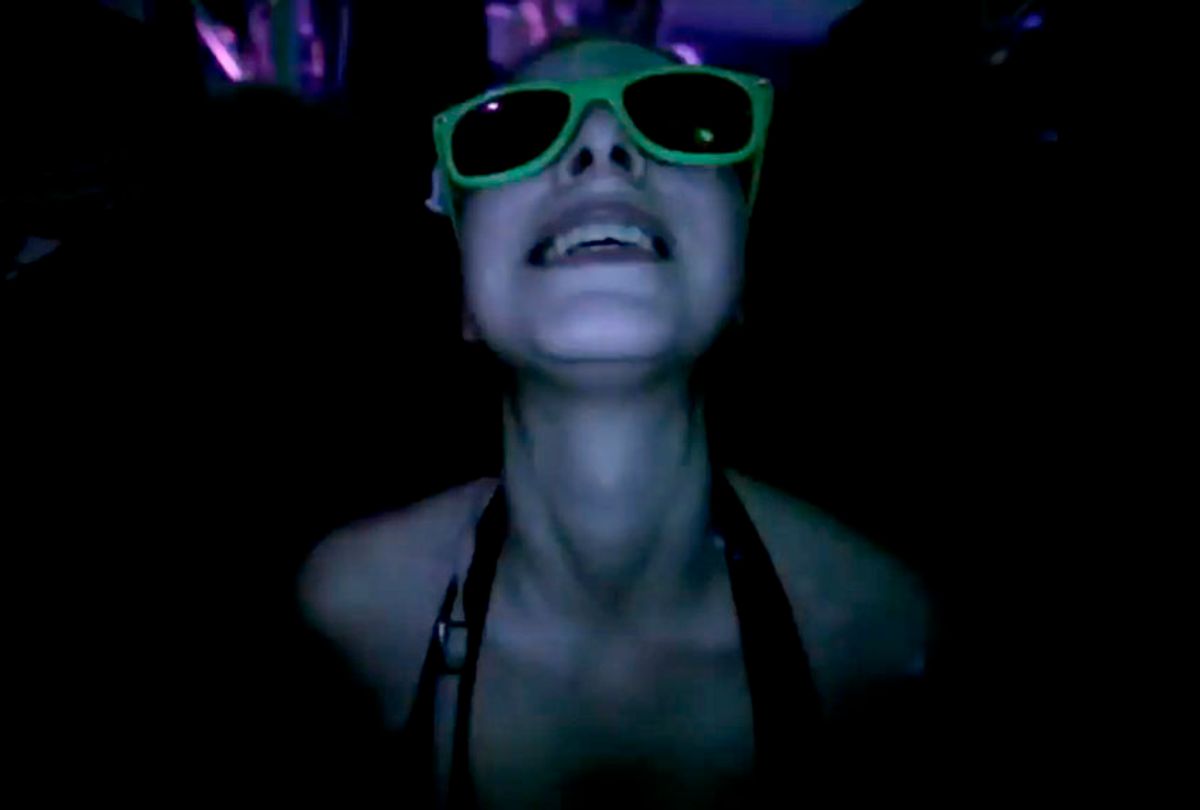

Canadian filmmaker Dominic Gagnon took 400-500 hours of YouTube footage and assembled it into 107 minutes to create the fabulous collage film documentary, “Going South.” The film, which had its North American premiere at the recent Camden International Film Festival, features a series of vloggers, from transgender teen Chloe to Scott, who runs a vlog for guys who want to engage in sex tourism in Thailand, plus a flight attendant, a guy with grills, Justin, a recovering alcoholic, a grandma who plays fantasy adventure games, and a man who insists the earth is flat among many, many others.

Gagnon shrewdly juxtaposes these various characters who are at times fascinating, at times boring—do we really need to see the flight attendant unpack her groceries or share her room service order?—or even disgusting, as when a group of guys use a beer bong and vomit. But as hard as it may be at times to watch, it is also hard not to stop watching. “Going South” becomes hypnotic as viewers wait to see what comes next, making connections between the vloggers and vivid images, such as trees on fire, or a cruise ship swimming pool during a storm.

Gagnon’s point may be that we have started to reach a saturation point with who or what we will watch—some of the vloggers get a whopping 30 hits; others, thousands. But perhaps he is simply holding a mirror up to our society’s need to present their lives publicly 24/7. Why do we watch? The filmmaker met and talked with Salon to find out.

What prompted you to make a doc out of YouTube footage?

I lost the use of my right eye in 2007, and that was only two years after the introduction of YouTube in our lives. At the time, it was not that interesting to me to use YouTube materials because it was not personal; it was more people uploading their VHS tapes on to the internet. There was no original content. But when the YouTube mania started, YouTubers were casting [posting] their everyday life and documenting their everyday life. I thought it was a good way for me to go back to documentary filmmaking without using a camera, because I couldn’t do that anymore. It was uncomfortable for me to use the eyepiece. It was like looking at reality through a hole in the door. YouTube was my option if I wanted to make film, and collage film has always been something I cherished.

Why did call the film “Going South?”

This is a new series I’m making with Cardinal Points. “Of the North,” “Going South.” I’m working on “East” and then “West.” I was screening “Of the North” here at the Camden International Film Festival, and a man asked me what I was going to do next. I said I was “Going South.” I didn’t know the meaning because English is not my language. When he explained the meaning, I thought, “Wow, this is such an inspiring title!” I was not making a film about tourism and resorts.

How did you secure the permissions of these folks to use their materials and what did you explain to them about your project?

I don’t ask any permission. It’s public already. All they are looking to be seen or heard. I don’t feel I distort their message or content. It’s like archival material. Of course, it’s edited with other things, but it’s not about asking them if they’d like to be in the theater or be on that screen or TV set. It’s already out there. If I would ask permission, it wouldn’t be, “Can I use your footage,” it would be, “Do you want to be in a film with these other folks?” I don’t think I could ever reach a consensus. After working 2-3 years on a project and have the components reflect and mirror each other, it’s a long process. If I remove one thing out of it, it’s going to fall apart.

As an artist this is the risk I’m taking. I don’t sell the film I don’t make money off them. I cite them in the end, so you can see it’s a big ad for their channel if they want visibility or subscribers. I’m helping them [by] doing this. Working with his method, I have extreme empathy for these people. My ethic is not to disappoint them if they see themselves in my film. That’s always been my line. I’m waiting. Maybe some people will hear about it. I’d be super happy to hear their reaction. The film is made and it’s out now. There’s no way it will be changed. There are 1,000 copies around the world now. I will eventually post it online. It’s taken from the ecosystem and given back. It’s just an edit. Those images are all over. You can show them anywhere.

READ MORE: Tom Arnold is on “The Hunt for the Trump Tapes”

Your tone can be seen as satirizing and/or celebrating these folks. How do you want audiences to read your film?

Both. Most of them satirize themselves, too. Chloe, I keep watching her channel and now she has to do publicity for products that are given to her. It’s so funny, she knows it’s all bullshit, and she’s being satirical about her own condition. That’s why I say empathy. I understand them. I chose them for a reason. They appeal to me.

It’s really easy to mock people, but it’s not fun. You don’t want to see that on a screen. It’s nice to mock reality and human existence. The technology we have and what we do with it, it’s mockable. These YouTubers expose their conditions — how hard it is to find support, subscribers, there are hard working conditions. They show it all. I’m with them, not against them.

Why do you think that they record and we watch?

I have learned that over the years, all YouTubers have to deal with an algorithm that more or less manipulates — for example, they can’t have a break because they wouldn’t be favorited by the algorithm. If you post every day, you have a better chance to make the home page and have more views. It pressures them to make content, and [laughs] they end up doing really simple, banal things. The idea is to post content, not have an interesting idea, just document their daily life, and they have tens of thousands of followers.

Why did you structure the film in six chapters with intertitles?

I don’t know. Destabilization. I did it in another film in the '90s, and I thought it was nice. “Going South” is really chaotic in the first third—it’s the chaos of images, and there is no shape to it. Slowly I shape it but coming back with the title and saying to the audience, this is one part, and there are six coming. The intertitles don’t make sense, but in the end, they do make sense, so they are guiding and misleading at the same time to make people as comfortable as possible in their discomfort. By the end, the parts are getting shorter and shorter and shorter, so even time-wise, it fucks you up. [Laughs.]

“Going South” is very sensory-oriented. How did you construct the film to generate meaning and emotion through the juxtaposition of clips?

I think it’s trial and error. I want to share the good combination I get. I feel it. It’s not something I want to create or provoke, but I recognize it in the footage. I make a cut and it’s something I discover. It often happens by accident. I don’t know why. It’s the hardest thing for me to talk about — why. If I wrote songs or poetry, I would say it’s my style; I have my own obsessions, certain things I like. If you look at my films, they repeat themselves. These are my obsessions.

What observations do you have on American life about race and class and even gender from what you saw and included?

I got a good image bank, it was really large. I made no effort to balance things. I don’t try to make films that represent everybody. It’s a snapshot of what’s online. There are all kind of filters—geographical, because some stuff is censored on the web in certain countries, because of copyright infringement; the language can play a role if I use material or not; and after that, all those people. What I observe from it is that it’s mostly white. If you think about YouTube, most users are white men aged 15-35 or 40. If I make a film, of course, there is always a high proportion of those guys. That’s what the snapshot gives you.

What fascinates you as a documentarian that makes you take this approach to storytelling?

I feel like online culture is really dystopic, and it goes beyond . . . it has to be problematized differently than traditional documentary practice. It’s a global culture first, and it is people who have money, or own a phone — not everybody owns a phone! — already you have class, gender, etc. in a global context. The main thing is getting likes and subscribers. It’s a super-capitalist exercise. Economical rationality: everything has a price and every move in your life as a YouTuber is about money, likes, etc. That’s what I see. I don’t see gender, it’s who has access and what do they do with it online. I make a lot of observations, but that’s not what my film is about.

“Everyone is strange or weird in some way,” one vlogger states. How are you strange or weird?

I can spend hours in front of my computer watching others on the internet while I don’t even have a Facebook account. I have a Hotmail address. This is the only way to reach me in life. I am not a user, I am an observer. In that sense, it’s a bit freaky. I know how to access most platforms. I’m in your family picture book. I’m everywhere. If I’m interested in something I will go for it. That’s a bit weird.

Shares