"One Day in September" is the definitive account of one of the most devastating and politically explosive tragedies of the late twentieth century: the massacre at the Munich Olympics, which set the tone for nearly thirty years of renewed conflict in the Middle East. The excerpt below, taken from the introduction and first chapter, reveal the joy and hope the world had for these games, and how quickly that bright atmosphere turned dark.

They were billed as “The Games of Peace and Joy.” The 1972 Olympic Games, held in the southern German city of Munich, were to be the biggest and most expensive ever mounted, with more athletes representing more countries than at any previous sporting event.

At 3 P.M. on August 26, 1972, the world watched as ranks of tall Greek athletes marched into the packed Olympic Stadium, in the north of the city, to bathe in the warm sunshine and thunderous applause.

As most of the 10,490 athletes present at the Games milled around the stadium, jostling for a better view, groups of whip-cracking Bavarian folk-dancers entertained the crowds. Next, 5,000 doves were released into the blue skies over Munich. Sixty men wearing Bavarian national costumes fired antique pistols into the sky, signaling the arrival of the hallowed Olympic flame carried from the Peloponnese, the site of the ancient Olympics. With the Munich beacon lit, the Games could begin.

The opening ceremony was a moving experience for the West German officials who had fought tenaciously to bring the Games to Munich. Hand-Jochen Vogel, the mayor of Munich from the 1960s until just a few weeks before the Games began, was bursting with pride during the ceremony. “It was emotional,” he said, “in a good sense.”

Bavarian officials hoped the event would confirm Germany’s rehabilitation as a civilized society, expunging memories of the Second World War and the Infamous 1936 Berlin Olympics, which Hitler used to glorify Nazi ideology. They invited massed ranks of the media, a grater concentration than ever before, to witness the festival of sport and the redevelopment of West Germany.

“The first thing you felt on arriving in Munich was this utter determination of the Germans, whether they be Olympic officials, policemen, journalists, or indeed the general population of Munich, to wipe away the past,” said Gerald Seymour, a reporter at the Games with Independent Television News (ITN) of Britain. “We were totally overwhelmed by the sense that this was the new Germany. It was a massive attempt, and it hit you straight away, by the Germans to appear open and modern and shorn of their past. Friendliness was in overdrive.”

At least 4,000 newspaper, magazine, and radio journalists travelled to the Bavarian capital, along with another two thousand television journalists, announcers, and crews. They fed tales of grit and courage to a television audience of nearly one billion souls in more than one hundred countries around the world. New satellite technology made it the mass-media event of the century.

Reconciliation between former enemies was a worthy goal, and the Germans worked feverishly to build an Olympic site the entire world could enjoy. A majestic Olympic Stadium was constructed on the wasteland alongside a sprawling Olympic Village where the athletes would stay.

But there was no greater confirmation of Germany’s rehabilitation than the presence at the Games of a delegation from Israel. The Jewish state, still struggling to forge a relationship with West Germany, sent its largest ever team of athletes and officials, several of them older Eastern Europeans still bearing physical and mental scars from Nazi concentration camps. To discourage any memories of Germany’s Nazi past, the two thousand Olympic security guards were dressed in tasteful, light-blue uniforms and sent out to charm the world, armed with nothing more than walkie-talkies.

“The atmosphere was . . . to let everybody feel that Germany has changed from the time of 1936,” recalls Shmuel Lalkin, the head of the Israeli delegation. “It was an open Olympic Games.” Across the vast Olympic site, dominated by a 950-foot-high television tower and a futuristic tented cover, a party atmosphere soon prevailed. Even entry into the Olympic Village was easy for competitors and autograph hunters alike. “The atmosphere was . . . enjoy yourself, see that Germany is not the same as it was.”

However, many of the Israelis had mixed feelings about their presence in Germany. Henry Herskowitz, a competitor in the rifle shooting, felt a degree of pride that Jews were returning to raise the Israeli flag on German soil. It proved the Nazis had not killed their spirit. But Jewish fears of Germany run deep, and before he left Israel, Herskowitz “had a feeling that something might happen.” Herskowitz was the athlete chosen to carry the Israeli flag during the opening ceremony, and in his darkest nightmares he had visions of being short while carrying the Star of David around the Olympic Stadium.

Terror did not strike at the opening ceremony, and the sprinter Esther Shahamurov, now Roth, one of the brightest Israeli track stars, marched just a few yards behind Herskowitz, also buoyant with pride. “It is a unique feeling to march while the Israeli flag is in front . . . There are many Jews around the world; you sympathize with them and they sympathize with you. You feel that you have to represent them.”

For Roth, the Olympics were “better than a dream.” “When I went there my eyes were opened . . . I saw people from all over the world, I didn’t know where to look first.” She remembers the Olympics as a feast for the eyes: so much color, so many different nationalities. “It was very beautiful, not only for the athletes, but for everyeone . . . You see an athlete and you can tell by his physique the sport he is in. For instance, the people who play basketball, they are so tall you can hardly stand next to them. The wrestlers, they have those ears, you can see the flesh in their ears . . . It was an amazing experience,” recalled Roth.

Shortly after 4 A.M. on the morning of September 5, 1972, a small gang of shadowy figures arrived on the outskirts of the Olympic Village and silently made their way to the six-foot-high perimeter fence supposed to offer protection to the thousands of athletes sleeping within.

Creeping through the darkness carrying heavy sports bags, the group made for a length of the fence near Gate 25A, which was locked at midnight but left unguarded. The thirty-five-year-old leader of the small troop, Luttif Afif, a.k.a. “Issa,” had carefully chosen the point at which his men were to enter the Village. On previous nights he had seen athletes climbing the fence near Gate 25A while returning drunk from late-night parties. Security was lax and none of the athletes had been stopped. Issa dressed his seven colleagues in tracksuits, reasoning that if the guards saw them they would assume they were just sportsmen returning to their quarters.

Jamal Al-Gashey, at nineteen one of the youngest members of the group, remembers the tension building as they approached the fence. As they drew closer they came across a small group of drunk American athletes returning to their beds by the same route. “They had been forced to leave the village in secret for their night out,” Al-Gashey said. “We could see they were Americans . . . and they were going to go over the [fence] as well.” Issa quickly decided the foreign athletes could give his group cover if they helped each other over the fence. “We got chatting,” recalled Al-Gashey, “and then we helped each other over.” He lifted a member of the U.S. team up onto the fence, which was topped not by barbed wire but by small round cones, and then the American turned and helped to pull him up and over.

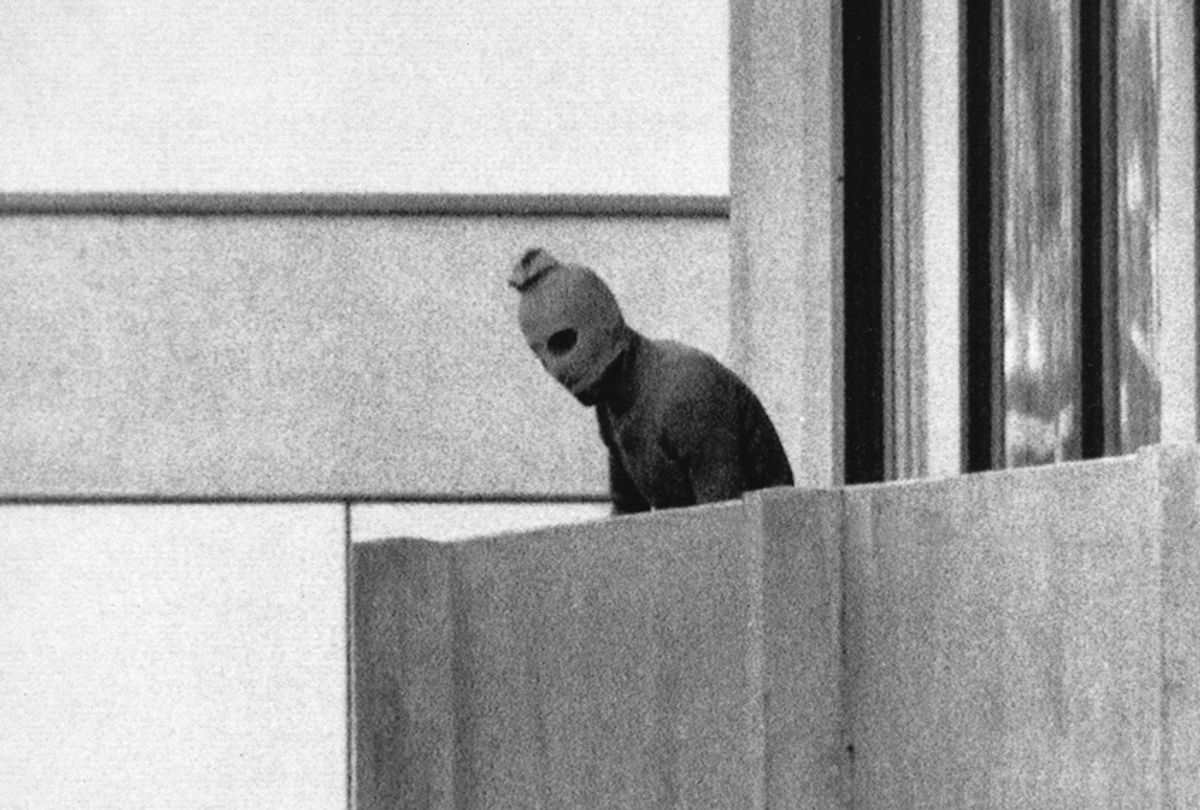

Several officials, including six German postmen on their way to a temporary post office in the Village Plaza, saw the groups climbing the fence with their sports bags at around 4:10 A.M. But as Issa had assumed, none of the passersby had challenged them because they thought the fence-climbers were just athletes returning home. “We walked for a while with the American Athletes, then said goodbye,” remembered Al-Gashey. The group split up and stole through the sleeping Village to a drab three-story building on Connollystrasse, one of three broad pedestrianized streets, adorned with shrubbery and fountains, snaking from east to west through the Village. Even if the unarmed Olympic guards or the Munich police had been alerted, it would probably have been too late. For the eight men were heavily armed terrorists from Black September, an extremist faction within the Palestinian Liberation Organization. The fedayeen (“fighters for the faith”) were carrying Kalashnikov assault rifles and grenades, hidden under clothing in the sports bags, and they were fully prepared to fight their way to their target: 31 Connollystrasse, the building in the heart of the Olympic Village that housed the Israeli delegation to the Olympic Games. The new entrants were about to make their mark on the XXth Olympiad.

The Black September terrorists knew exactly where to go after scaling the perimeter fence. The attack had been weeks in the planning, and Issa and his deputy, “Tony” (real name, Yusuf Nazzal), worked undercover in the Olympic Village to familiarize themselves with its layout. Issa had lived in Germany for five years and attended university in Berlin. He took a job in the Village as a civil engineer. Tony, who is believed to have worked for a Munich oil company, went undercover as a cook.

The temporary jobs allowed both men to roam freely through the Village. As the world reveled in sporting glories, Issa and Tony sat on a bench on Connollystrasse together and played chess in the sunshine, watching the athletes coming and going from No. 31. Tony proved to be a particularly good spy. Luis Freidman, an official with the Uruguayan team, which was sharing 31 Connollystrasse with the Israelis, even found him inside the building at 8:00 A. M. on September 4. Speaking in English the Palestinian shyly told Freidman that he was a worker in the Village and that someone in the building occasionally gave him a few pieces of fruit. Friedman walked over to a crate of apples and pears sitting on a table and gave him all the fruit he could carry.

The next night Issa and Tony led their squad of terrorists quickly through the Village. They paused just around the corner from the Israeli building, changed out of their athletes’ tracksuits into the clothes they would wear during the attack, and then headed towards Connollystrasse (named after the American athlete James B. Connolly, a gold-medal winner at the 1896 Olympics).

There were twenty-four separate apartments in No. 31: eleven of the apartments were spread over two floors, with an entrance on main street and a garden at the back; the rest were on the fourth floor, which was topped by two penthouses. Twenty-one members of the Israeli delegation were housed in the duplex apartments 1–6. The block was also home to athletes and officials from Uruguay, who had other duplex apartments, 7–10, and several more on the fourth floor, and the Hong Kong team which occupied five apartments on the fourth floor and the two penthouses. A German caretaker lived in the remaining duplex with his wife and two young children, and a steward had the remaining fourth-floor apartment.

Shortly after 4:30 A. M. the terrorists assembled at the far end of the building, opened the blue main entrance door to apartment 1, and crept into the communal foyer. Whereas the other ten duplexes opened directly onto the street, apartment 1 had a foyer with an elevator and stairs leading up to the fourth-floor and penthouse apartments and down into the lower-level streets and parking lot. The door was never locked.

“When we got to the building, the leader of the operation gave out jobs to us,” Al-Gashey said. “My job was to stand guard at the entrance of the building and the others went up the steps into the building to begin the mission.” With Jamal guarding the entrance, the rest of the group positioned themselves outside apartment 1, home to seven Israelis, and tried to open the door with a key they had obtained during their preparations for the attack.

Inside the apartment the Israelis were fast asleep: Amitzur Shapira, athletics coach, Kehat Shorr, marksmen coach, Andre Spitzer, fencing coach, Tuvia Sokolovsky, weightlifting trainer, Jacov Springer, weightlifting judge, and Moshe Weinberg, wrestling coach. Yossef Gutfreund, a wrestling referee, was the only one awakened by the faint sound of scratching at the door.

Gutfreund crept out of his bedroom and into the communal lounge, not wanting to wake the others. As he stood barefoot by the door, listening for a sound, it opened just a few inches. Even in the dim light, with sleep still misting his eyes, he saw the eyes of the fedayeen and the barrels of their Kalashnikov assault rifles. Sleep turned instantly to horror. “Chevre Tistatru!!” (“Take cover, boys!!”), screamed the 6-foot, 3-inch Gutfreund, thrusting his two-hundred-ninety-pound bear-like physique against the door as the terrorists abandoned their keys and began pushing from the other side.

The apartment erupted. Tuvia Sokolovsky, who shared Gutfreund’s room, jumped from his bed and ran into the communal lounge. Gutfreund was wedging the front door closed with his body.

“Through the half-open door I saw a man with a black-painted face holding a weapon,” said Sokolovsky. “At that moment I knew I had to escape.”

Sokolovsky screamed to his friends in the other rooms, leapt back into his bedroom and sprinted towards the window. “I tried to open it but couldn’t. I pushed it with all my force.”

Behind him three terrorists were desperately trying to dislodge Gutfreund and shove the door open. They pushed with their hands, they braced their legs against the other side of the corridor wall, and then they stuck the barrels of two Kalashnikovs through the small opening and used them as levers in the frame. Man-mountain Gutfreund held them for at least ten seconds before they spilled into the apartment, forcing him to the ground at gunpoint.

In a blind panic, Sokolovsky finally broke the window open. “It fell out and I jumped and began to run.” They feyadeen ran into the bedroom behind him. “The Arab terrorists started shooting at me and I could hear the bullets flying near my ears.”

Sokolovsky never looked back. He ran through the small garden barefoot in his pyjamas, rounded the corner onto and offshoot of Connollystrasse, and hid behind a raised concrete flowerbed.

Back in apartment 1 the terrorists pulled Gutfreund off the floor and began rounding up the other athletes. Shapira and Kehat Shorr, a Romanian who fought the Nazis during the Second World War, were both bundled out of bed. But one of the Israelis was awake and moving quickly. As Issa burst into another bedroom he was confronted by Moshe Weinberg, who grabbed a fruit knife from a bedside table and slashed at the terrorist leader, slicing through the left breast pocket of his jacket but missing his body.

Issa fell to one side, and one of the other terrorists standing behind him fired a single round from his rifle directly at Weinberg’s head. The bullet tore through the side of Moshe’s mouth, exiting on the other side to leave a gaping wound. The force of the bullet sent him spinning, blood pouring from the side of his face.

According to Al-Gashey, Weinberg attached Issa “and grabbed him.” “At that moment, another member of the group entered the room and opened fire on the athlete who was holding the leader and had taken his weapon.”

The attack was now horribly real. Blood, Jewish blood, was once again being shed on German soil.

Shares