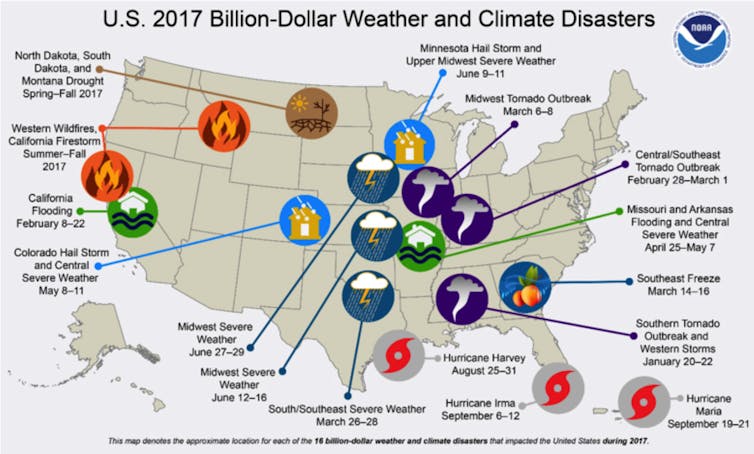

As Hurricane Florence made landfall, we could not help but reflect on the enormous human and financial toll of weather and climate-related disasters from last year. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), these disasters, which included severe storms, cyclones, floods and wildfire, exceeded US$300 billion — making 2017 the costliest year ever.

Since taking control of the U.S. federal government, President Donald Trump has systematically tried to dismantle and defund climate mitigation and protection programs.

At home, he has attempted to eliminate funding for climate change research through proposed budget cuts for the Environmental Protection Agency and NOAA. Luckily, Congress rebuffed these cuts in March.

Abroad, he has withdrawn the United States from collective international efforts including the Green Climate Fund, created to support developing countries reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to the effects of a changing climate. Most notably, he exited the landmark Paris Agreement, saying it imposed “draconian financial and economic burdens” on the U.S.

Band-Aid solutions

At present, only remedial relief and financial Band-Aids are offered for each new “storm of the century,” a tag that has been applied to both Hurricane Lane in Hawaii and Hurricane Florence in the Carolinas.

Yet, Trump claims his administration has carried out an “all-out effort” and is “ready for the big one that is coming.”

Nothing could be farther from the truth.

(NOAA Climate.gov)

Our research has focused on the ways that environmental change affects people’s lives, and the means through which communities are addressing and adapting to changes. To us, an “all-out effort” requires many of the strategic and long-term policies, programs, and commitments to collective action that have been done away with.

A recipe for disaster

First and foremost, the government response to weather and climate-related disasters requires compassion. Actions speak louder than Tweets.

Following last year’s hurricane season, government-led relief efforts in Puerto Rico sharply contrasted those in Houston. The differences were stark: the amount invested in recovery, the tone and attention given, and the speed with which life returned to normal.

The fact of the matter is, the president never valued life in Puerto Rico the same way as he valued life in Texas. As the one-year mark of Hurricane Maria came and went, Trump questioned whether the 3,000 lives lost in Puerto Rico were part of a conspiracy to make him “look as bad as possible.” Rather than acknowledging this mass casualty a year after Maria, Trump opted to guard his own ego.

The president opted out of the Paris Accord and eliminated homeland climate protection programs, including Obama’s Climate Action Plan. These initiatives would have reduced emissions and supported steps to help communities be better prepared for the future. Both explicitly recognized the importance of mitigation and adaptation efforts to slow down climate change and to protect citizens from its effects.

Real action

Mitigation efforts reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve carbon storage to limit the adverse effects of climate change, such as higher temperatures, evaporation rates and sea levels. These are, in fact, some of the key factors that made last year’s hurricane season so intense.

As Hurricane Florence approached the Carolinas, atmospheric scientists at Stony Brook University developed a forecast for the storm, and looked at how climate change had shaped it. They found the effects of climate change had increased the size of the storm by 80 kilometres and the predicted rainfall in the Carolinas by more than 50 per cent.

Adaptations are actions that help communities reduce the risks from hurricanes, drought, wildfires or floods that will be amplified by the effects of climate change. For example, governments can make critical infrastructure such as fire stations or hospitals more flood-resistant, update floodplain planning and improve water capture.

Such preventative actions could go a long way in reducing disaster-related costs — both human and financial. For example, the U.S. EPA estimates that damage to coastal property from sea-level rise and storm surge will cost US$5 trillion until 2100 if greenhouse gas emissions aren’t reduced. However, that figure shrinks to US$810 billion when coastal adaptations occur.

The administration has repeated tired industry talking points by suggesting climate protection programs implemented under former president Barack Obama were harmful to the economy. Just this week, the Department of the Interior rolled back the Obama-era methane rules, citing “unnecessary burdens on the private sector.”

By withdrawing from international agreements and eroding domestic programs designed to support climate resilience, Trump endangers the public’s welfare and its purse. Financial Band-Aids are not enough. It’s important that Americans remember this.

For the Trump administration to truly commit to an “all-out effort,” it must embrace policies that not only provide immediate relief, but also plan for and reduce harm for all. Until then, the current Republican policies that have risked life, property and the environment will continue to do so.

# # #

Sameer H. Shah, PhD Candidate, Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability (IRES), University of British Columbia; Devyani Singh, PhD Candidate, University of British Columbia, and Scott McKenzie, PhD Candidate, Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability (IRES), University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.