I had been reading all my life—as a child on summer vacations, as a student, and as a literature professor—but until I got sick and had to read for hours at a time to make the day go by, I never knew what reading could be. I read while I rested because it was all I could do. My life felt useless, my sense of self-worth was barely detectable. Then one day a stranger who subsequently became a friend gave me a book that captivated me. I couldn’t get it out of my head; it was if I’d been kidnapped. I’m an enthusiast where books are concerned, but this book—“Sir Vidia’s Shadow,” Paul Theroux’s account of his 30-year friendship with V. S. Naipaul—gripped me in a way few books had ever done. There was no reason for it, since I’d had no interest in either author. I was retired, sick, and unable to work; I hadn’t written anything in a long time, but I sat down at my computer and started writing, determined to find out what was going on.

Now, as I read Naipaul and Theroux, incidents from my own life began to appear; pieces of my past offered themselves unbidden. Instead of trying to analyze what the authors had written, I started to analyze the material their writing had unearthed. I began to make connections between parts of my life I’d not made before, stumbled on patterns I’d never noticed. It occurred to me that if the works of Naipaul and Theroux could have this effect, surely other books could, too. Branching out, I read what was around the house—literary criticism, journalism, contemporary novels, detective fiction—and sure enough, while the feelings these books evoked were different, the structure of the experience was the same. Just as before, by observing my reactions to what I read, I saw things about myself I didn’t want to see—envy, a desire for fame, assumptions of moral superiority that were completely unfounded. Under the pressure of remembered incidents from my past, criticisms I’d started to formulate about the authors I was reading turned to dust.

From time to time, I paused to speculate on the ways reading had impacted my life—I’d started out using it as a refuge and as a vicarious form of adventure, then it metamorphosed into professional capital and a source of creativity. And now it had become a path of self-discovery. Not an easy path, but a transformative one. I went from book to book, and from memory to memory, and thus did the night of my illness yield up its treasure, bringing me face to face with who I was. . . .

I was in Florida when I received the book. We were moving. The house—built in 1948, a block from the beach—was too much to take care of, and, though I didn’t like to admit it, the garden took its toll. I loved the house and garden. They were full of charm. But we weren’t up to it anymore. It was time.

We’d hired someone to help us sort through our belongings—keep it, sell it, give it away—Patty could get rid of anything in a trice. One day she asked her sister to take her place. It was the day I was supposed to go through my files, what remained of my career as a teacher and writer. Contrary to expectation, Maggie wouldn’t let me throw away much. She’d been a lawyer on Wall Street for 23 years, been married to a professor of screenwriting at NYU. After he died, people had wanted his papers, and that made her think someone might want mine. It was flattering, if unrealistic. Sitting in my study, talking about what to keep and what to let go of, we got to know one another, and I lent her a copy of my memoir, “A Life in School.” A week later, Maggie sent me a book in return. The book was “Sir Vidia’s Shadow” by Paul Theroux.

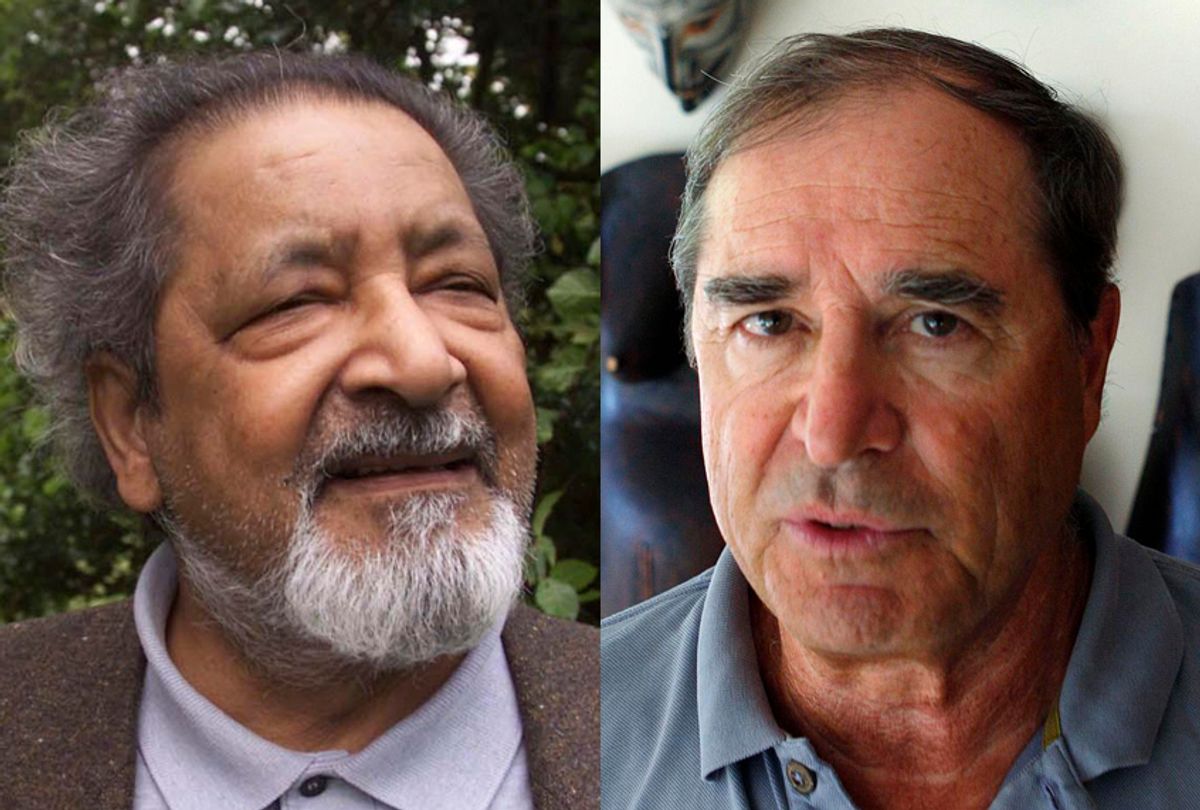

“Sir Vidia’s Shadow” is a memoir of the friendship between Theroux, a well-known American novelist and nonfiction writer, and V. S. Naipaul, a Trinidadian author of East Indian descent who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2001. Not the sort of book one would expect to have life-changing consequences. I was about to go on a week’s vacation in Italy and thought I’d glance at the book before leaving, just to confirm my belief that it wouldn’t interest me. I’d never read anything by Theroux and had a negative impression of Naipaul, based on a piece of his I’d read in the New Yorker.

I was wrong about the book. When I opened it, I was hooked immediately. I read it on the nine-and-a-half-hour flight from New York to Frankfurt, and then on the flight from Frankfurt to Bari. I read it in Italy—I had plenty of time since I had to take every other day off from the rigors of the tour we were on; it was the first time I’d been able to travel for many years—and I finished it on the way back to the States. This was not airplane reading—not an action-adventure story or a tender romance; it was a memoir, but not about recovery from a breakdown or overcoming a great obstacle. It was about a 30-year friendship between two men. One did not save the other from drowning, they didn’t have sex with each other or each other’s wives, or try to wreck one another’s careers. They wrote letters back and forth, had lunch, and went on the occasional excursion. I couldn’t put it down. And when I finished it, I wanted to read it again. I wanted to remain within the aura of the book. And I wanted to discover why it fascinated me so.

I’m an enthusiast when it comes to books. If I read one that moves me, I tell all my friends about it and will sometimes give it as a gift to the unsuspecting. This book was different. It had reached inside and grabbed me where I lived, gotten into my system like an allergy or an infection. But I didn’t know why. What had made me susceptible? . . .

Theroux explains in an afterword that he did not compose from notes or diaries but from recall. Long swatches of dialogue; detailed descriptions of countryside, interiors, meals eaten 20 years ago; what people wore, the expressions on their faces, the jokes they told—it all came to him unbidden. The details, the moments, are charged with the urgency of things that have to be said; the rhythm and sequence of the sentences communicate this. The sentences seem shot from guns, taut and targeted. There are no flourishes or special effects. With the book’s focused forward movement, always covering ground, the style conforms to one of Sir Vidia’s maxims: never let your language call attention to itself. Theroux writes exactly as his mentor might have wished: he stays close to the ground, hews to particulars. He makes his points without stating them. The question is: what made these memories so vivid for him: why does he not need a single prompt? And why, whenever I picked the book up, could I not put it down? Was it only the writing?

READ MORE: Soon-Yi Previn and Woody Allen’s strange charm offensive: An enigma wrapped in scandal

Here’s a passage. Theroux, Naipaul, and his wife, Pat, are seated at the Kaptagat Arms, a hotel in northern Kenya. Political unrest has driven them out of Kampala, the capital of Uganda, where Vidia and Paul first met. They both had appointments at Makerere University, Vidia as a visiting author, Paul as a member of the faculty. In this scene they’ve just learned that the hotel is about to close. This upsets Pat, who starts to cry. Then, “ ‘Oh, my, Vidia, look,’ she said, and gestured towards a waiter. ‘His poor shoes.’ ”

They were broken, without laces, the counters crushed, the tongues missing, the heels worn. . . . The sight of the shoes reduced Pat to tears once again. Each time she saw the man wearing them, she began to sob. I did not tell her that Africans got such shoes second- and third-hand. . . . The shoes, like the torn shirts and torn shorts they wore, were often merely symbolic.

“Don’t be sad, Patsy,” Vidia said. “He’ll be alright. He’ll go back to his village. He’ll have his bananas and his bongos. He’ll be frightfully happy.” (53)

Theroux doesn’t say a word about what he thinks this scene reveals. Though it says a great deal about Pat, about Vidia’s attitude toward her and, even more, toward Africans, and about the author’s relationship to both of them, Theroux doesn’t comment; he moves on, letting the evidence mount. Here, and in the book as a whole, you feel a case is being made, but what case? Is it about the kind of person Naipaul is? Is it about the author’s position in relation to Naipaul? Is it about writing as a profession? The exact nature of the agenda isn’t clear. A case is being made, the evidence is accumulating, but the facts veer this way and that. They point in different directions. To figure out what’s really being said in this memoir of a friendship you have to keep reading till the end. But after I got to the end I still had questions: what is it Theroux wants us to believe about his friend? What are we supposed to make of the way he portrays himself ? Why, when I read this book, did I feel like an old war horse whose blood jumps when he hears the bugle sound? Why did the relationship between the young writer and the better-known, older writer seem so important to me? Why were the stakes so high?

Shares