Maybe it’s because like Christine Blasey Ford, I know exactly what it was like to be a 15-year-old girl back in the ’80s. Maybe it’s because my younger daughter turns 15 in a few months. Or maybe it’s just because I’m a human being who recognizes that teenagers are also sentient human beings. And I know that keeping the past in the past isn’t an option for all of us and that conversely, cruel, reckless kids don’t always just grow out of it.

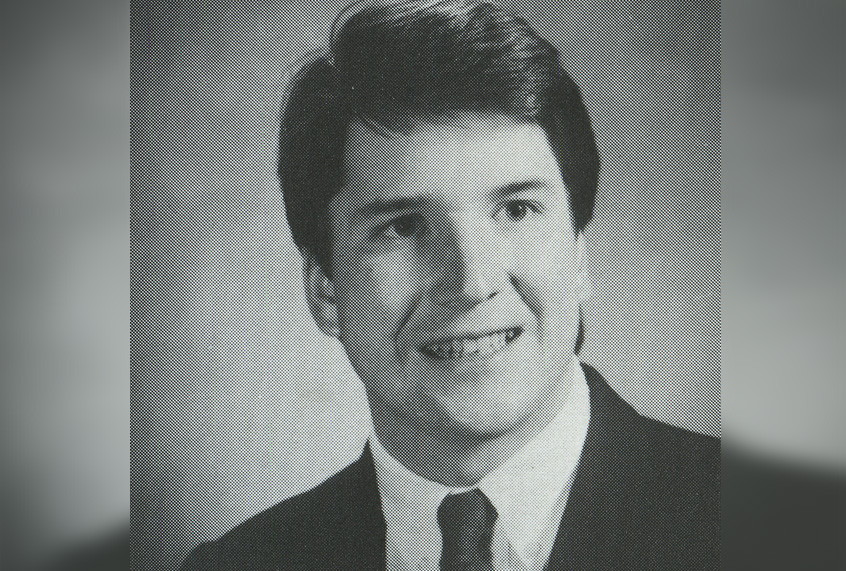

In the emotionally overwhelming conversations around what Dr. Ford alleges happened to her at the hands of Brett Kavanaugh, one enragingly pernicious argument going around has been the old trope about youthful folly. Earlier this month, unfailingly terrible New York Times op-ed writer Bari Weiss declared, “Brett Kavanaugh has a reputation as being a prince of a man, frankly, other than this. Now, I believe her. I believe what she’s saying. I’m just saying, in the end of the day, it is one word against another. Let’s say he did this exactly as she said. Should the fact that a 17 year-old, presumably very drunk kid, did this, should that be disqualifying?… I’m thinking of it today from the perspective of, let’s all think about our worst instance that’s happened to us in this world and imagine it paraded out in front of the country.”

It’s not hard to see who the “us” in this story of the the “worst instance” is. It’s not the woman.

Similarly, a USA Today feature earlier this week framed the Kavanaugh hearings in the context of examining how events “in a person’s youth – from a social media misfire to a criminal conviction — can hinder their ability to earn an income for decades to come,” and how a one “may be damaged professionally — or live in perpetual fear that they will be — because of youthful mistakes.”

A recent Atlantic feature by a juvenile justice advocate, while pointing out the very real discrepancies in how the system treats youthful offenders based on race and class, added that “[a]lmost all kids break the law at some point. They might shoplift, violate an open container law, buy drugs, drive dangerously, or get into a fight. Yet almost all kids outgrow their period of recklessness. . . . At some point, dumb kids start acting like responsible adults. It’s highly unlikely, for instance, that I’ll ever again drive 100 miles an hour on the Mass Pike (sober, mind you) or steal a giant Sunoco flag as a trophy for my dorm room (no comment). Rarely do even serious youthful offenses indicate a criminal future.”

Why, it’s as if being accused of “a social media misfire” or “stealing a Sunoco flag” and “sexually assaulting a person” are all equivalent transgressions. What an appalling lack of empathy it takes to make that leap.

READ MORE: Ford-Kavanaugh showdown is an important battle: But now progressives must fight the war

I used to say that I was “lucky” I’ve never been raped, that I’ve only endured what feels like an average amount of groping, sexual harassment, and physically threatening situations. Ever since somewhere around November 9, 2016, though, it’s been occurring to me more and more that maybe not getting raped could be one’s baseline expectation. But then, that would involve no longer assuming that assault is likely part of one’s life experience. It would mean that assault isn’t normal. Spoiler: It’s not.

That I somehow managed to get through my youth — including plenty of drinking and partying and foolish behavior — without being assaulted or assaulting anyone else serves as a reminder to me now that assaulting people is not a common “mistake” that people make, even “very drunk kids.” If my future career prospects were never harmed by my idiot teen behavior, maybe it’s because my idiot teen behavior never physically harmed another person. Maybe it’s because most of the people I associated with were not — whether they were drunk or sober — predators.

Unfortunately, some of those people, it turned out, were. My friends who survived them live still with the scars of what happened all those years ago, when their trust was betrayed by someone who hurt them both physically and emotionally. Someone who maybe even laughed about it. And when I look now at my daughters and their friends, I see young men and women who know right from wrong perfectly well, who may be impossible in many regards but are morally accountable for the actions they take and decisions they make. They know bullying when they see it. They know what abuse looks like. And they don’t dismiss that kind of behavior as a “mistake.”

The world has changed dramatically since my own Regan-era adolescence. But though we didn’t always have the vocabulary for it — or the confidence our experiences would be believed — I can confirm that assault is assault in any time, and a young girl’s experience of it is unchanged regardless of what moment in history it happens in. As Padma Lakshmi wrote recently in the New York Times, recalling her own rape when she was 16, “Some say a man shouldn’t pay a price for an act he committed as a teenager. But the woman pays the price for the rest of her life, and so do the people who love her.”

Assault is not an effect of boisterous, school kid enthusiasm. No one commits an act of abuse by mistake. Whatever you believe truly happened to Dr. Ford all those years ago, and what Brett Kavanaugh did or did not do, it diminishes the experience of survivors to brush off what is being clearly described as assault as teenage hijinks. And what do you think it tells our current crop of teenagers, when a persistent narrative playing out in front of them right now is that, like drinking too much or pulling pranks, hurting women is just a common and forgettable part of growing up?