At a Mississippi rally Tuesday night, Donald Trump dropped his obviously coached efforts at pretending to respect Dr. Christine Blasey Ford — who has accused his Supreme Court nominee, Brett Kavanaugh, of sexual assaulting her in high school — in favor of open mockery. As Trump suggested that Ford's inability to remember mundane details from 36 years ago meant that her accusation was false (he failed to mention that corresponding evidence has backed up her timeline), the crowd responded eagerly with a "Lock her up!" chant. As approximately everyone knows, that chant originated during the 2016 election to imply that Hillary Clinton was a criminal, but now has metastasized to cover any woman who speaks out against Republican misogyny.

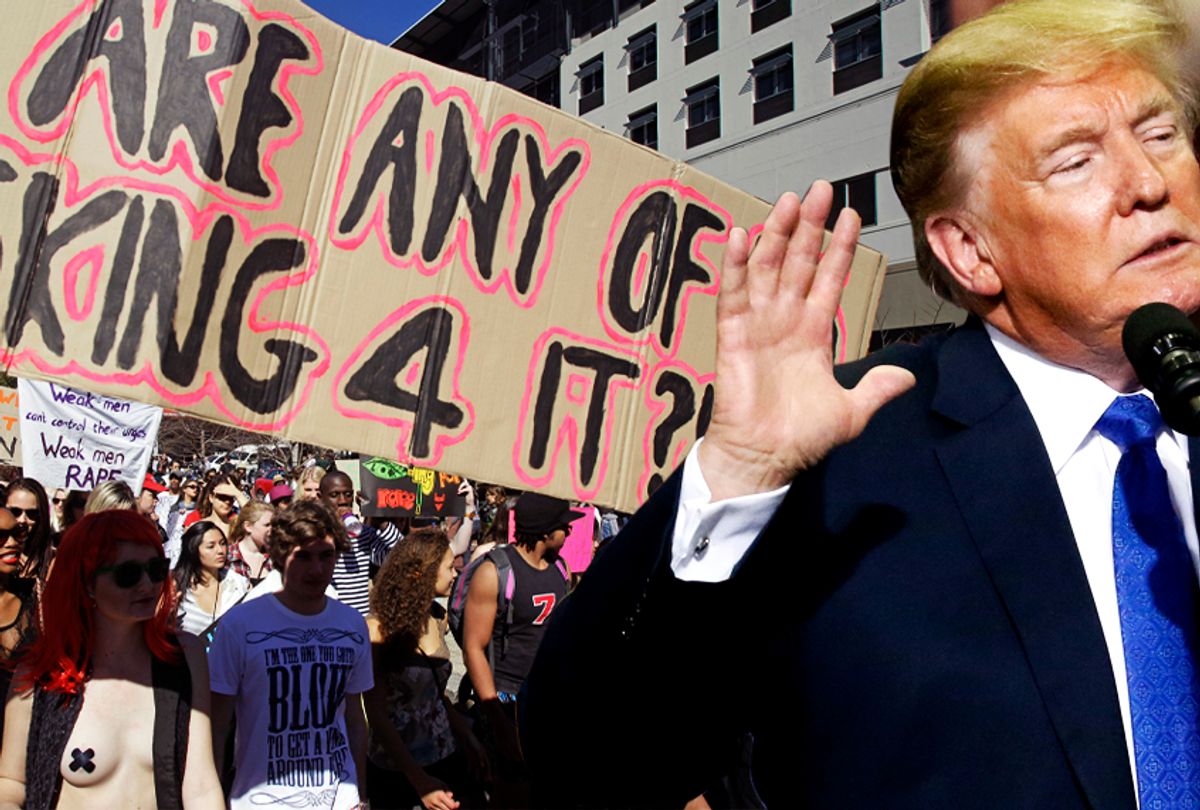

On the same day Trump was sharing his ugly thoughts, I was looking through photos from the New York City Slutwalk from seven years ago. It was a lovely October day that year, warm enough still for many women to lean into the name and wear very little clothing, some even going without shirts and walking around in just jeans and bras. While the premise of the protest — that it was time to stop blaming victims for rape and start blaming rapists instead — was grim, the tone of the day was jubilant. (New York magazine reporter Emily Nussbaum was marching with me that day and recorded her observations in a larger essay about 21st-century feminism.) As we marched through the streets chanting anti-rape slogans, there was a real sense that we were changing the conversation about sexual abuse, moving away from a world where the responsibility for preventing rape was primarily put on women and toward one where we began to hold men accountable for their own choices.

Watching Trump's sneer as he mocked Ford for her courage, while the men behind him laughed and the crowd demanded the imprisonment of women who report assault, it was hard not to wonder if the last seven years have been in vain. After all, Trump himself was elected after a tape of him bragging about sexual assault was released. There's still a strong chance that Kavanaugh will be seated on the Supreme Court, despite his audacious dishonesty about his past, despite his other accusers and despite corroborating evidence underlining Ford's fundamental honesty about what happened in the summer of 1982.

But ultimately, I have to believe that the rising tide of female rage over sexual harassment and violence, which has culminated in the past year in the #MeToo movement, has made a dent, In fact, Trump's disturbing display on Tuesday night was evidence of it. The virulent backlash against women who speak out is, after all, a reaction. Misogynists are pushing back because they feel threatened. They feel threatened because they know, on some level, that anti-rape activism is working and there is a very real danger that any dirty little secrets they have lingering in their past may come back to haunt them.

Slutwalk started early in 2011 in Canada, when a few thousand feminists hit the streets of Toronto, many in "slutty" clothes, to protest a police officer who had been part of a supposed sexual assault training advised college students that they shouldn't "dress like sluts" if they didn't want to be raped. Many women erupted in rage, sick to death of being told that their personal choices caused rape rather than, you know, rapists. Women were sick of sexists treating rapists not as criminals but as bogeymen used to threat women into compliance with restrictive gender roles.

While the choice of many of the Slutwalkers to dress in skimpy clothes and use curse words drew a great deal of criticism from all corners, ultimately the strategy was successful in conveying a message: Women should be allowed to dress how they want and act in ways that sexists deem "immodest" without fear of violent reprisal; men who assault women should be the ones held responsible. Slutwalk protests exploded across the globe, including in such cities as Sydney, Seoul and New Delhi. Women showed up in all manner of clothing, from extremely modest to nearly naked, reminding people that people of all sorts get raped and sending a message of female solidarity against the idea that anyone deserves to be assaulted.

These protests, it's fair to say, sparked new interest in fighting back against sexual assault, especially on college campuses. Feminist students started pressuring schools to do more to deal with sexual harassment and assault, and federal investigations into schools that allegedly overlooked such abuses exploded in number. The Obama administration started White House campaigns to raise awareness about sexual assault. The concept of "affirmative consent" — which, despite what haters might say, simply means only having sex with someone you know for sure wants to have sex with you — became a widespread concept. Lady Gaga performed an anti-rape song at the Oscars in 2016, flanked by outspoken sexual assault survivors, cementing the fact that what had started with Slutwalk was now an international cultural phenomenon.

Slutwalk itself hasn't gone away, although -- as inevitably happens in our capitalist system -- what was once hip and organic has been co-opted by corporate culture. Now there's an annual Slutwalk in Los Angeles, headed up by celebrity personality Amber Rose, that involves costumes, musical acts and VIP tickets. But feminist criticism has largely been muted about this, as Rose seems sincere in her desire to fight rape culture, even as she is clearly using this to amplify her brand.

READ MORE: Feminists won't back down: What's next for #MeToo after the Kavanaugh vote?

Many people talk about #MeToo as if it came out of nowhere, or was simply building on women's anger at Trump's election. But in reality, this moment has been building for some time. Now it's clear that sexist anger over it has also been building in response, culminating in the election of Trump and the ugly mockery of women who speak out about the kind of sexual assault that Trump and some of his supporters regularly engage in.

The backlash is disturbing and upsetting, but feminists should understand that these predatory men are on the defensive because they see anti-rape activism working, and they are afraid. The early days of this movement against sexual abuse, despite the seriousness of the topic, were often fun and invigorating because they were defined by women coming together, supporting each other and being creative. In retrospect, however, it was inevitable that once feminists started winning battles on this front, men who had previously felt untouchable would get angry and start to lash out. The only question now is whether feminists will continue to fight now that the battle is getting heavier. The wide, deep support that Christine Blasey Ford is getting — and her courage in stepping forward at all — suggests they will.

Shares