Directed by Jenni Gold and packed with celebrity interviews, “CinemAbility: The Art of Inclusion” tells a Hollywood story that has long been overlooked — namely, how the film industry’s depictions of various physical and mental disabilities has profoundly shaped how the rest of the world treats individuals with those disabilities. From individuals of small stature and those in wheelchairs to the protagonist of “Forrest Gump,” “CinemAbility” explores how the entertainment industry has taken advantage of the disabled for a quick buck and yet also furthered the cause of spreading compassion and acceptance.

Gold told Salon that the idea for the film grew out of interest in a documentary about her, a director with a disability. But she wasn’t wild about that idea.

“Looking back I started noticing a disparity in portrayals about the power that the media had to influence society’s understanding of people who are different,” Gold told Salon. “But the real story is also that when I had been written about as, you know, ‘a female director uses a wheelchair’ in the newspaper, some good friends of mine in the business came over and said, we want to do a documentary about you.”

“And I said no, that’s silly. I haven’t done anything, and how boring,” she continued.

But the idea led to an aha moment for Gold, who turned around and pitched the idea of a wider scope. “They said, ‘Yeah it sounds like a lot of work.’ And it turns out they were right, it was quite a piece of work,” she said. “But I told them, if you don’t do it I might, and they said, that’s OK, and that’s how it began.”

Actor Danny Woodburn, a little person who advocates for disability rights, is one entertainment professional who appears in “CinemAbility.” Woodburn is best known for playing Mickey Abbott on “Seinfeld,” which he recounts as a watershed moment for little person representation on screen.

“I would say my first ‘Seinfeld’ episode was kind of a turning point,” Woodburn told Salon. “And then to be called back as a recurring role, I don’t think that little people had had that kind of visibility, in terms of [playing] the guy next door, the pal that hangs around with the troop.”

“I mean, certainly we had famous actors in the industry,” Woodburn said. “Billy Barty, Michael Dunn [“The Wild Wild West”], Felix Silla [“The Addams Family” TV show], people that have been working for decades before me. Billy Barty of course having his daily show in the Los Angeles market, his kid show, which — I didn’t grow up in Los Angeles, I never saw the kids’ show, I wasn’t exposed to it. But it was impactful to see Billy doing what he does and then, of course, to see Billy do episodes of ‘The Love Boat.'”

Woodburn pointed to Barty’s groundbreaking moment correcting another character’s language with regards to little people on “The Love Boat” as a precursor to a famous scene between Mickey and George Costanza (Jason Alexander) on “Seinfeld,” in which Woodburn “gave the refresher course” on the correct terminology two decades later.

“I think the first time the term ‘midget’ might have been used and corrected would have been probably in the episode of ‘The Love Boat’ with Billy, if memory serves,” Woodburn said. “I think that was probably the first time I had seen the word used and then corrected, or at least Billy definitely gave the [term] ‘little people’ a national, or in this case probably international, acknowledgement as the proper use. And that was back in the ’70s.”

“People think ‘little people’ spawned off in the ’90s,” he added. “I get to do the same thing [as Barty did] in my first episode of ‘Seinfeld’ when George missteps and uses the term.”

The disabled individuals I spoke with, along with the others interviewed for “CinemAbility,” all appear to be keenly aware of how their performances aren’t merely works of art or entertainment, but statements that can be used to positively impact the experiences of the groups they represent to millions of people.

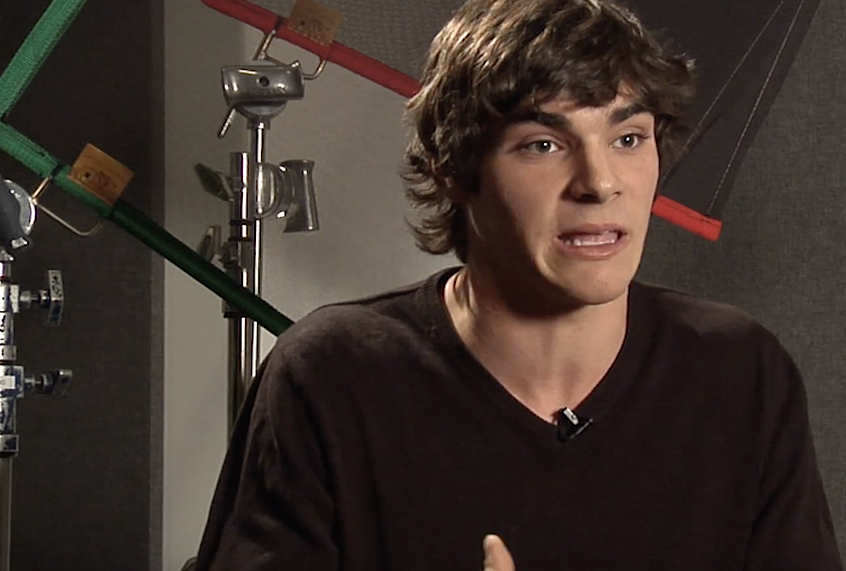

R.J. Mitte, who played Walt. Jr. in “Breaking Bad,” points to his role as an example of how to portray characters with disabilities in “a non-discriminatory way.” Mitte, like the Walt Jr. character, has cerebral palsy.

“My character wasn’t based around disability. My character was based around being in ‘Breaking Bad,'” Mitte told Salon. “I felt that it was a great example of showing someone with a disability in a real-life way. Not in a, ‘Oh my God, he has a disability and that’s why this character is doing all these things, because he’s the disabled son.’ That’s one element. This isn’t a disabled person. This is just a person. I think we did a great job with showing that and showing the humanity.”

This also speaks to a criticism that I, as a person on the autism spectrum, have had of a number of pop culture properties featuring characters who directly or indirectly share my condition, like “Atypical,” “The Good Doctor,” and arguably “The Big Bang Theory.” Even when those series intend for their representations to be positive, a common pitfall is that they often reduce a disabled character to the reality of his or her disability. Being a little person or having cerebral palsy or living with autism certainly can have an impact on how you live your life, but it isn’t the same thing as defining who you are altogether.

In the best shows out there, like “Breaking Bad,” a character like Walt Jr. can be a person who plays a key role in the story as the moral counterpart to the depravity of his father and, to a lesser extent, his mother, with his disability being a component of who he is, rather than the totality of it.

This is one of the central themes of “CinemAbility,” and it directly ties into another important subject broached by the film — namely, making sure that people with disabilities are represented in films that are intended to depict their experiences. It isn’t enough to simply have characters with those disabilities; if you want to be authentic, and for that matter do some real-world justice for people whose disabilities have often caused them to be denied opportunities, you need to actually cast disabled people as actors, crew members and other creative personnel.

“We had 150 kids with intellectual disabilities in that movie,” Peter Farrelly told Salon about his 2005 comedy “The Ringer,” which is set in the Special Olympics. “Of all the movies I’ve ever made, it was the most satisfying and fun. It was just a ball. Every morning, you show up and you got these 150 kids . . . the vast majority were extras but yes, we had a lot of speaking roles who were people with intellectual disabilities. To show up, it took you 20 minutes to get through the hugs before you got working. It was a love fest and one of the greatest experiences of my life.”

“These kids, for those ten weeks, were stars,” Farrelly added, saying that they were constantly stopped on the streets of Austin by fans asking if they were in the film. “‘Hey, you guys are in the movie ‘The Ringer?’ They were beloved in that town, everywhere they went. It was amazing. It was something I’ll never forget. It was probably the highlight of my career.”

Farrelly also admits that even when he has acted with the best of intentions, he has had to have oversights pointed out to him. He recalled a character in a wheelchair from his 1994 classic comedy, “Dumb and Dumber,” who was not played by a real-life quadriplegic.

“After that, my buddy Danny Murphy, who is my friend who’s a quadriplegic, he gave me a load of shit: ‘What the hell are you doing? Do you know how many actors are out there who are in wheelchairs who never get a chance, and you hired a kid who’s not in a wheelchair?'” Farrelly said. “I thought, oh f**k, I hadn’t thought about that.”

“It was a wakeup call,” he said. “After that, we always tried to hire disabled actors to play the disabled roles.”

And that is how progress is made.

While Hollywood, like any business, has its share of prejudices and harbors its share of bigots, there are likely far more cases of well-intentioned people making honest mistakes than there are of malicious players deliberately trying to humiliate or hurt the disabled. That doesn’t excuse those mistakes, but it is a reminder for empathy as we continue to push for progress. “CinemAbility” is a step in the right direction of using information and compassion to bring about the kinds of changes that are needed.