An alarming new report from the University of North Carolina shows that news deserts — communities that lack a local newspaper, or are served primarily by “ghost newspapers” — are growing across the United States. According to UNC’s research, the country has lost nearly 1,800 local newspapers since 2004, and many more have lost the ability to comprehensively cover their communities.

Rural counties with poorer, older populations are most at risk — 500 rural papers have shuttered since 2004. These communities are also less likely to see a digital start-up help fill the void — as funding for both for- and non-profit models are more available in metro areas, and many rural counties across the U.S. still lack broadband internet access, which is critical for delivering online news. Even Iowa, whose connectivity rate is supposed to be the highest in the nation, lacks broadband service in much of the state, as Columbia Journalism Review's Lyz Lenz reports, which renders delivery of online news inefficient at best — to say nothing of producing it from within those underserved areas.

According to the report, almost 200 counties in the U.S. have no local paper now, and nearly half have only one, which is more likely than not a weekly, not a daily paper. The South registered the highest number of counties without a paper — 91, a significant jump over the Mountain (28) and Midwest (27) regions. In Georgia, 28 out of 159 counties lack a newspaper, and statewide, daily and weekly newspaper circulation has plummeted nearly in half since 2004, from 3.1 million to 1.6 million now in the eighth most populous state.

California lost the most daily papers of any state, and overall has seen 15 percent of its papers shuttered since 2004. Circulation is down 38 percent across dailies and weeklies, with two Golden State counties lacking a paper altogether.

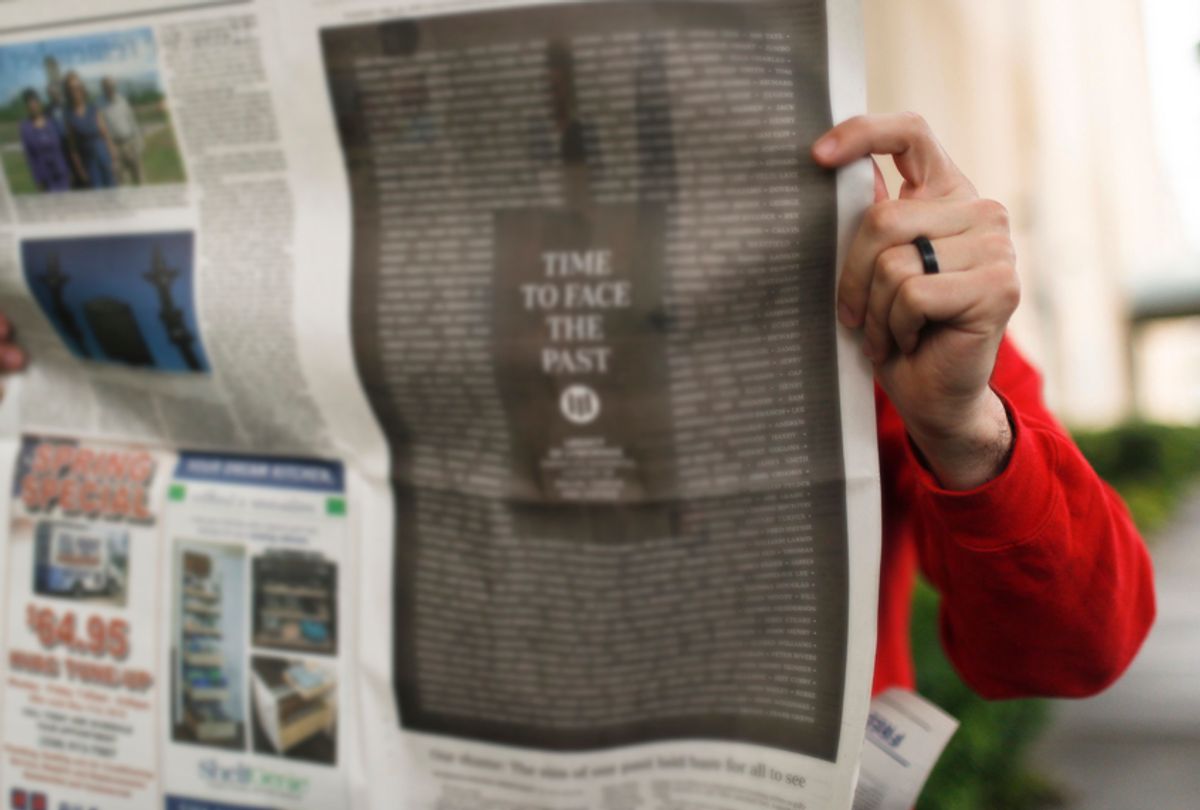

While some communities' coverage might look safe on paper, the report also highlights the growing issue of "ghost newspapers," outlets where local coverage has been so gutted that the local newspaper has lost its ability to comprehensively cover its community.

Local ownership of papers is also at risk, which can affect the amount of local news a paper covers. Nearly one-third of U.S. newspapers and two-thirds of dailies are now owned by just 25 companies. The largest newspaper owner in the country, GateHouse Media, has been buying up small-town papers at a rate Nieman Lab's Ken Doctor earlier this year called "insatiable," incorporating a corporate efficiency model that in some cases results in fewer reporters on staff and more content shared across the paper network, with editing for all papers done in Austin, Texas. "Content is our number-one priority," Reed told Doctor, noting that "he’s unwilling to publicly commit to any new level of funding or staffing to meet that goal."

If you're reading this on broadband in a city with a thriving metro daily paper and multiple digital start-ups, in a tab next to your open Washington Post subscription and with one eye on MSNBC, you might not see immediately how any of this affects you, let alone democracy. But the diminishment of local news coverage reverberates beyond the news deserts themselves, affecting how national new outlets based on the coasts cover the entire country as well as how comprehensively the federal government can address public health issues and environmental disasters. And it can contribute to disengagement — not only from local civic life, but also from the media in general, if the remaining regional and national outlets aren't reporting stories that speak to those underserved audiences' concerns.

As Pulitzer board co-chair Joyce Dehli points out, declines in local news coverage are deeply tied to large outlets' ability to report accurately on the entire country, leading to media failures like the "we didn't see Trump coming" phenomenon of 2016:

In truth, journalists from big coastal news media, with a few exceptions, have never done a good job of covering people in the vast middle of the country. I know this well from decades of living and working as a journalist in Midwestern states as a reporter, editor, and vice president for news for a company with dozens of newspapers in small and mid-size cities across the country.

But big media journalists once routinely reviewed and absorbed the work of colleagues at good local newspapers, especially regional newspapers that excelled at statewide coverage. Journalism from smaller newspapers informed that of larger ones. The Associated Press (and others, to a lesser degree) connected each to the other’s journalism and offered its own robust state reports, too.

Today, less local journalism—and less meaningful journalism—moves through a diminished network. Perhaps under the old scenario, the growing disaffection of rural and small-city residents would have been widely recognized much earlier. So might another under-reported story: the apparent willingness of many people, across the country, to tolerate bigotry and misogyny. This, too, is a story for local, as well as national, journalists.

The attempt by national outlets to try to fill in the knowledge gaps left when local coverage shrinks can lead to simplistic "What's the Matter with Appalachia?"–style coverage from afar, in which the complexities of local politics and culture are flattened for a national audience by writers who aren't working in the community, exacerbating a divide between the urban media centers and the rest of the country.

And what fills the news gap for local audiences when their newspapers shrink or fold? There are bright spots in the digital start-up landscape, including Vermont's VTDigger. Launched by journalist Anne Galloway after she was laid off by the Rutland Herald in 2009, VTDigger now boasts a monthly readership of 300,000, 19 full-time employees and an annual budget of $1.5 million.

But TV news is the more likely answer across the country, and conservative-leaning Sinclair Media, praised by Donald Trump as "far superior to CNN," is the largest owner of local TV news outlets. In 2017, Sinclair was fined $13.4 million by the FCC for failing to disclose certain segments were actually paid advertisements. And while Sinclair's news stations are designed to serve local markets, they also receive "must-runs," segments produced by the company that have been criticized as "politically tilted" and which are mandatory to run across all Sinclair stations, nationwide.

On cable, Fox News dominates the news channel ratings, and Fox anchor Sean Hannity, who the Washington Post reports has such frequent back-channel contact with the president that "he basically has a desk" in the White House, is the most-watched host. Earlier this year, Media Matters' Matt Gertz conducted a study of Hannity's segments during the first year of the Robert Mueller investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. He found that Trump's relationship with Hannity has helped the president advance a narrative "that special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election is a sprawling conspiracy that justifies the president using any means — including trials of the law enforcement officials who initiated the probe — to stop it."

When right-wing outlets are part of a larger media landscape, voices like Hannity's and Sinclair's "terror watch" segments are balanced by local shoe leather reporting and watchdog investigations that hold powerful institutions, both public and private, to account. As 6th Circuit Appeals Court Judge Damon J. Keith once wrote, "Democracy dies in the dark," a slogan that the Washington Post has adapted as their rally cry for accountability journalism in the Trump age. Every shuttered local paper, or those zombified by a lack of local coverage, dims our national light just a bit more.

Shares