It is a strange thing for an Englishman to discover that he has Native American ancestry. It is even stranger if that person is a geneticist who writes about genealogy. Nevertheless, that is my story.

My family tree was compiled by my father’s cousin, a keen genealogist, using the traditional forms of ancestry detective work—births, deaths, marriages, military service records, and so on. He identified one of my 16 great-great-great-grandfathers, a man with the splendid moniker Lycurgus Handy, whose life did not match the grandeur of his name. Lycurgus died destitute in a poorhouse in London in 1920. Further digging revealed that his grandfather was one Benjamin Handy, AKA “The greatest horseman in the world.”

Ben was the owner and star performer in Handy’s Traveling Circus, a popular touring act in the 18th century United Kingdom. He was married to another performer, Mary Huntley. On their wedding certificate, dated 1818, it describes her as “savage.” Mary was the daughter of Neil Huntley, one of two “chiefs” from the Catawba Indian Nation, brought from America to join the circus for their exotic native horse-riding skills.

Genealogy is probably the number one hobby of U.S. citizens, and in Britain it is second only to gardening. In family trees, kudos derives from having noteworthy, famous or infamous ancestors. This is not a surprise — we are interested in interesting people, and we often create a sense of identity from presumptions about the people from whom we came, rather than who we actually are.

In the last few years DNA has been added to the genealogy tool kit, our genomes being not only the ultimate document of who we are, but the log book of our ancestors. More than 10 million people have used the services of either 23andMe or AncestryDNA to try to establish some sense of their ancestors’ origins. When I took the 23andMe test, the results were almost entirely unsurprising — 49 percent is hues of blue, meaning European, and 50 percent is yellow, which is their code for southern Asia, meaning India. My father is English, my mother Indian. Some of the missing percentage point is marked red, 23andMe’s color code for the Americas. This fraction of my genome is identified as “Native American.”

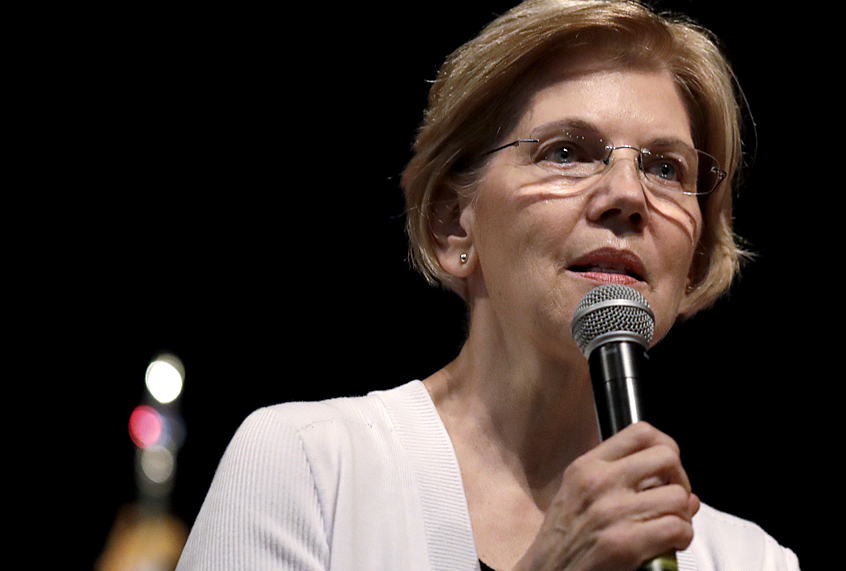

After several years of claiming Native American ancestry from family lore, and subsequent public mockery bordering on racism by President Trump, the news broke earlier this week that Senator Elizabeth Warren’s genome harbors DNA that indicates that she had at least one Native American ancestor many generations ago. In the last few days, geneticists have been arguing over the results. This is not least because there are different methods for crunching the ancestral data hidden in genomes, and, as with all good science, the validity of the methodology is being scrutinized by experts. These tests comprise huge volumes of data, profoundly complex statistical analyses, selection of techniques and interpretation. Of course, none of this is apparent in the way data are presented. Senator Warren’s results are quite possibly typical for the amount of so-called Native American DNA that millions of Americans with predominantly European heritage harbor, and more than mine, even with a named Catawba ancestor.

None of this matters. Her tribal status is not being contested, as she does not have one. DNA is not part of the set of criteria anyway. The fetishization of our genomes as some kind of route to personal identity is an emerging 21st century trend, fueled by genetic genealogy companies playing into the common need or desire for cultural membership. Ironically, it is virtually irrelevant.

One of my ancestors was a Native American, and a fraction of my DNA gets labeled as Native American. The true oddity of this situation is that the genealogy is probably right, the genetic genealogy is probably not, and neither say anything about me. The likelihood is that the section of my DNA that is identified as Native American is just noise in the system generated by poor data about Native American DNA.

Even if the population genetics of Native Americans were better known, and that sliver of DNA is really from indigenous ancestors, they are still not relevant to tribal status. There are no special tribal markers in DNA, and no tribes use genetic genealogy for establishing membership, nor should they.

The political implications of Senator Elizabeth Warren’s claims of indigenous ancestry are messy. It is possible in an argument for both parties to be wrong. President Trump’s continued mockery is sneering and unkind but far from atypical; Senator Warren’s claims and subsequent use of some inconsequential genetics is specious, and according a statement issued by the Cherokee Nation are “inappropriate and wrong,” and undermine tribal interests.

I am descended from a Catawba chief, which doesn’t make me a Native American, and it doesn’t afford me any of the cultural or political valences that come with membership of a tribe. Neil Huntley is one of 128 male ancestors from that tier of my family tree. His genetic contribution to me may well be zero; his cultural influence unequivocally is. DNA has virtually no power to determine identity.

Ancestry is a matted web. There would be thousands, probably millions, of Europeans with similar claims, if their family trees could be drawn in such detail. I am not Native American, by rules determined primarily by Native Americans, regardless of what my DNA may or may not say. In that regard, Senator Warren and I are very much in the same tribe.