Ed Brubaker is one of American comic's most distinctive and accomplished voices. He has reimagined and rejuvenated popular superhero characters such as Marvel's Daredevil. Brubaker also (literally) brought the Captain America character Bucky (aka the Winter Soldier) back to life, and watched as he became one of the most popular characters in the multi-billion-dollar Marvel film franchise. In his more than 20-year career Brubaker has also written iconic characters such as Batman and the X-Men. He is also a writer on the hit HBO TV show "Westworld."

But in parallel with his success in writing for DC Comics and Marvel he has always maintained his love of noir fiction, a genre better suited for alternative and independent comics than mainstream superhero titles. The results of Brubaker's enduring love for noir include such award-winning comic books and graphic novels as "Criminal," "Incognito," "Fatale," "The Fade Out" and "Kill or Be Killed."

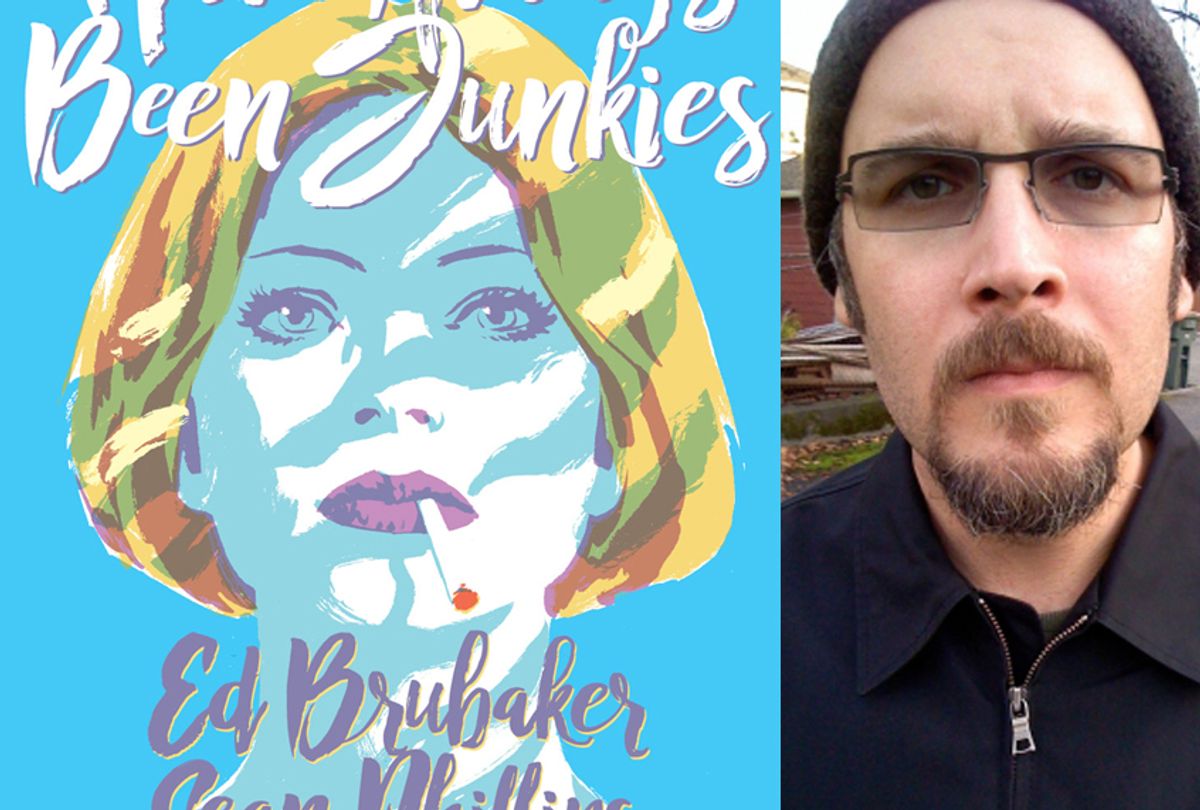

Brubaker's newest project is "My Heroes Have Always Been Junkies," which is now available from Image Comics.

In my recent conversation with Ed Brubaker, we discussed the origins of his love of comic books and graphic novels, advice for people trying to break into mainstream comics, the personal challenge of writing legendary characters such as Batman and Captain America, the obligation of the writer to speak personal truth and his thoughts on how American comic books and graphic novels have crossed over into the mainstream of Hollywood popular culture.

Brubaker also reflects on the relationship between creativity and sobriety and how those tensions are present in his new work. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

As someone who has written for DC Comics and Marvel, how did you find the confidence to write characters you did not create and to then put your mark on them?

When I started doing work for hire stuff, I was over at DC Comics. I did some work at Vertigo, a DC imprint, which included a mystery comic called "Scene of the Crime." The head editor at the time read that and then he asked me about writing "Batman."

I thought, “What, like a superhero comic?" I write crime stories, more personal stuff, and the head editor at DC said, “Well, if you can write a mystery, you can write a Batman comic. Batman's the world's greatest detective.” Then I started thinking about it. What is interesting about Batman? What parts of "Batman" as a mythology appeal to me, and what parts of Bruce Wayne or these characters around him are things that are reflective of me? I have the nostalgia for it. You take all of that and then just swing for the fences.

I broke in during the late 1990s, early 2000s doing the DC and Marvel stuff. I was coming out of alternative comics where I had drawn and written small comics for friends of mine. I wasn't paid very much. I was maybe making $10,000 a year. The idea of getting a job where I was going to get paid for every page that I wrote, and then I could write one of the most popular comic book characters with Batman, was an amazing turn of events.

When you create alternative or independent comics, you always have to explain to your relatives what you are doing. It was the easiest thing when I could call my relatives back in West Virginia and tell them, “Hey, I'm writing 'Batman.'“ Everyone knew the character and the stories.

I had a lot of friends who would come from alternative comics, and I would introduce them to editors and try to get them in. A couple of them would pitch ideas and you could just tell their heart wasn't in it. They were really just in it for the money. I always would tell my friends and others I was trying to help, “You have to figure out a way to make it as real as the stuff that you're doing that you own, or it will feel false to the editors and the readers. Allow yourself to feel ownership of the material while you're doing it, even knowing that you don't own it.”

There's a bit of that in all writing on some level. All writers live with a certain amount of denial because we all think we're going to be able to make a living as writers -- and if you stop believing that myth, you won't be able to succeed.

For example, I know I don't own Captain America. I know Jack Kirby and Joe Simon created Captain America, and they don't own Captain America either. But I'm going to write something that feels like what I would always have wanted to see Captain America do. I'm going to try and take ownership of the character as much as I can.

I got very lucky on that level, and that the people inside Marvel really liked what I did. They allowed me to make the "Captain America" book my own to some degree.

You knew the format, the voices, internal rhythm and logic of the narrative and universe.

With "Batman" or "Captain America," it's the same kind of thing where you know the parts of it that appeal to you. You always write the stories and characters that you want to read or that you would wish that someone would do. It's a fine line. For me, it got to a point where I’d just done so much of it. I was seeing them making all these movies out of everything now, and the industry just felt like it was shifting. I had built a big enough audience for the work that I was doing. At a point it was just more creatively satisfying to not do superhero comics.

Superhero comics have the same problem that superhero movies have: the third act. This is the part of the story where a bunch of people put on costumes and go around punching each other. Either the good guy wins or the bad guy wins -- but of course usually the former.

Comic book movies are doing great, but comic books as a genre of popular culture are not doing that well. How do you make sense of that dynamic?

Of course I'm going to have mixed feelings about it to some degree. At the time I wrote "Captain America" it was work for hire. Marvel didn't have their own movie studio and they weren't owned by Disney. Kids came to my house that year dressed as the Winter Soldier for Halloween because of the movie. That is pretty amazing.

Bucky was this dead character that no one would ever let be brought back. I feel like 80 percent of the people who ever wrote "Captain America" wanted to bring Bucky back. I got to "Captain America" when the company was willing to break some of their own rules. The only thing I pitched was that I wanted to bring Bucky back from the dead and have him be the character I had in mind. On a creative level it's really satisfying to see the Russo brothers and Joe Johnson make really good movies and see how Sebastian Stan is fantastic in the role as Bucky the Winter Soldier. I got to be in a scene with him and Robert Redford in "Captain America: The Winter Soldier," which is pretty amazing.

With this most recent transition, where comic books and graphic novels have gone from subculture to the mainstream of popular culture, what has been gained and what has been lost?

ComicCon is so huge now. I almost never go. I moved to San Diego when I was seven or eight years old. My dad got transferred there. I think that year or the year after, I discovered Comic-Con. It was the last year they were doing it at the El Cortez hotel and my dad took me and we got a room at the hotel. You could walk into any panel and I remember the first thing he did, we walked in, my father looked at the schedule and said “Oh, Bob Kane, the guy who created Batman, is upstairs showing you how to draw him.”

We went upstairs and watched Bob Kane in person explain how he created Batman. I was just eight years old or just about, and every year Comic-Con was the thing I looked forward to the most. There's still ways to enjoy Comic-Con, but it is really just overcrowded now that it is such a huge global gathering. A friend of mine started referring to it as "IP-Con" a while ago, and "Entertainment-Con" because it's so much more about TV shows than comic books.

It's kind of funny, it just became that comic books took over the entertainment industry. They all morph together into this big event. But there are little comic shows around the country that are still more comics-oriented. You have Heroes Con in Charlotte, Emerald City up in Seattle. There's still a lot of ways that the comics are still a very small supportive community of people who just love the art form.

Where did your love of comic books and graphic novels come from?

My dad was a commander in naval intelligence. From age four to seven we lived at Gitmo actually, before it was a prison. I'm sure those neighborhoods that I lived in are still there. I lived in Radio Point, which is the neighborhood where the Navy officers and their families lived. My dad grew up reading comics. One day he went into the office and asked his buddies if their kids had any comics they were done with because he wanted to start me and my brother reading early. He brought home this huge box of comics and some of them didn't have the covers on it. I remember there were some EC comics, some issues of Mad when it was still a comic-book size and "Fantastic Four" No. 6.

I started reading comics before I ever read a book. I would immediately sit down and just try to draw Spider-Man. Comics were in my blood from the time I was a little kid. When I was probably 10, I wanted to be a penciler. I only started writing so that I would have something to draw, and then as I got older and started reading more books, I realized I was more of a writer. I realized what kind of comics I wanted to do. When I was a kid, I just wanted to pencil Spider-Man. Now my interests are much different.

In your work on comic books and graphic novels such as "Criminal" and "Incognito," you write characters who are vulnerable. Can that level of personal openness be dangerous for a writer?

I come more from the school of "Write from your gut." I always feel like if you can empathize with your own characters, then you can make readers empathize with them no matter who they are. I tend to write some really damaged and troubled characters and try to make you, the reader, understand their thought processes. I feel like there are things I've read where just a single line is so honest and real that it vibrates through us. It can be four or five words and it just resonates so well. I feel like those moments are probably unplanned by the writer.

They're just those moments where the writer is so caught up in the poetry of their own words and the story that they're telling. I just follow the characters. When I'm writing a lot of the characters in "Criminal," they are not the kind of characters who are going to bare their soul. I feel like I have to try and show people something that they're not getting anywhere else. The only thing that we all have is our own experiences and our own honesty and our own things that we empathize with that we feel like other people could perhaps empathize with as well. I have to process all hat and put it into the work somehow and disguise it.

How did "Kill or Be Killed" come into existence? A story about a graduate student who goes on a murder rampage out of frustration and mental health issues is not boilerplate. There is a unique voice there. I actually suggested "Kill or Be Killed" to friends and colleagues and they told me it hit too close to home.

It came out of nowhere. I was actually starting to work on something else that wasn't coming together. I sat down and I just thought, “Well, what do I really want to write about right now?” This was eight months before the American presidential election in 2016, but it was a really ugly time in the world already. I had just finished "Fade Out," where I was trying as pretentiously as possible to just follow Alan Moore's footsteps and do, like, a serialized novel as a comic book. That was a really ambitious thing to try to take on.

Coming off that, I wanted to re-embrace what monthly comics were when I grew up. Somehow, the idea just hit me of this person who had to kill one person, a bad person, every month to stay alive. All the mental health aspects really came later. Writing "Kill or Be Killed" was born from just knowing a lot of people who had struggled with their own mental health issues when they were in college. I didn't go to college or grad school and had a lot of friends who did. I had roommates who had nervous breakdowns in the 1990s when I lived in boarding houses in Seattle. I absorbed a lot of what that world was like.

My mother was a therapist. My stepdad as well. I grew up hearing about therapy and having people at the dinner table analyze you. It was a lot of channeling my own frustration. The point of "Kill or Be Killed" is kind of obvious. We're all taught growing up that there are very basic notions of "good" and "bad," these fairy tales about morality and codes of morality, yet the real world is completely not like that. In the real world, criminals get away with it and moreover rich people get away with anything they want. The world just continues to be made shittier and shittier every day.

I feel like we're in a world right now where a lot of people would look at something like "A Christmas Carol" and be like, “Well, why do they have to have Scrooge change at the end?” He was totally fine.” No, he was the greedy miser that's a bad character.

How is this political moment with Donald Trump going to impact the type of art being produced in America? I can imagine a lot of really good stuff coming out of this moment and also lots of really on-the-nose, overly obvious work as well.

"Kill or Be Killed" has parallels with books such as "Fight Club" and "Catcher in the Rye." I even make a nod at the end to end of "Catcher in the Rye." It is important for writers to write whatever they feel like writing and tell the truth about the world as they're seeing it. No one wants to read art that’s an obvious polemic. But at the same time, there's a lot of really great stories that address things that are going on in the world.

Why the new book "My Heroes Have Always Been Junkies"?

I have long been obsessed with musicians and actors and writers and just famous artists who have all sort of been junkies. This started when I was a child. After my parents got divorced, my mom went into recovery and would take us to her AA meetings every Sunday for about five years when I was about age 8 up to 12 or so. I spent every Sunday morning at an AA meeting, eating doughnuts and cake and smelling cigarette smoke and listening to adults talk about all the terrible things that they’d done. It was just part of my world that I had never really written about too much.

Growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, there were all these rock stars who were OD'ing and dying. You just always had that connection between pop culture and drug culture.

For me, as a kid, going to those AA meetings, listening to all those stories, I very much romanticized it. I romanticized my mother as this tragic figure, perhaps because of that. I wanted to extrapolate that a little bit and tell this crime story about a young girl and give her a lot of my obsessions. Why does she do the things she does? I don't know.

Billie Holiday, Judy Garland, Philip K. Dick. I always see those figures as tragic. I also see them as just very honest and open. Maybe it was the same pain that they're trying to cover up or something in their life that also caused them to have to tell stories or write songs or paint pictures.

In terms of creativity, do you think it's easier or harder for people to work sober?

I think, generally, most great writers probably write sober. But I can't judge other people and I certainly wouldn't judge a drug addict. I would judge them for breaking into a family's house and stealing everything, of course. I wouldn't judge them for having their addiction, because I have known too many addicts, and I grew up around that world to some degree.

If you had to give advice to a younger version of yourself ,what would it be?

I've been very lucky in my career. I've gotten to work with a lot of great artists. I've gotten editors who were really supportive of my work and gave me great assignments that other writers would kill for.

I feel like I did pretty well. Literally, the only advice I would give myself is, “Don't do the X-Men.” I took that job as basically a fill-in when Mark Millar was going to take over the book and then he didn't do it and I was there for years. I did it because I told myself, “Well, you can't quit the X-Men.” I really was not into doing a team book. For me that was a time when I started being miserable because I was writing something that I should have been enjoying.

Never, ever work for hire where you take a job that you know you're going to dread. If you're writing your own books, just try to follow the characters and also try to find some honesty in there somewhere.

Shares