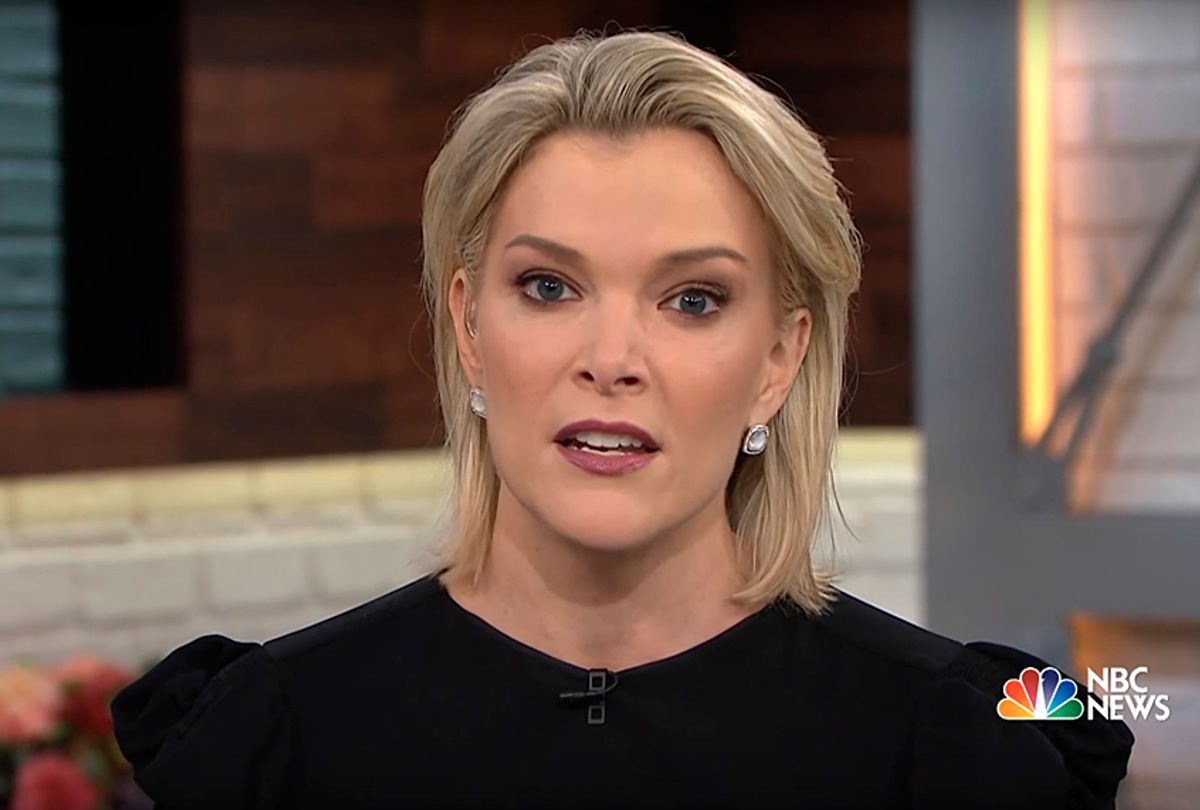

NBC news personality Megyn Kelly finds her career in a shambles this week after making what were – well – very Megyn Kelly-esque remarks regarding blackface Halloween costumes.

It should surprise no one that Kelly would find herself caught up in this controversy. After all, when she moved to NBC from Fox News in 2017, lured by a $69 million dollar contract, she brought with her a history of similarly racist comments, notably her 2013 insistence that both Santa Claus and Jesus Christ were white (“Jesus was a white man, too… He was a historical figure, that’s a verifiable fact, as is Santa. I just want the kids watching to know that.”), and in her disproportionate, hyperbolic 2010 coverage of the very small hate group, The New Black Panthers.

More surprising, perhaps, was the tenor of her apology. How could a well-educated woman like Kelly credibly claim ignorance of the verifiable fact, so to speak, that blackface was and is “awful” and “racist,” and is therefore out of bounds for Halloween? In part, the idea that a subject as patently racist as blackface is even open for discussion can be attributed to the raging discourse around “political correctness.” For many commentators on the political right, political correctness is merely emblematic of a society gone soft, unable to admit to uncomfortable truths like the (imagined) whiteness of historical figures like Jesus Christ or Santa Claus, or the (fallacious) innocence of children in blackface at Halloween, simply for fear that someone – usually a “minority” or other “special interest” – might take offence.

In reality, right wing, majoritarian disdain for political correctness speaks loudly of a social class that perceives itself to be under threat by the sweeping demographic changes in the U.S., constituted largely by those same minority groups; it reveals white supremacist, patriarchal fear of an America that is becoming increasingly diverse in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality. Indeed, Kelly’s central argument on Tuesday – “When I was a kid, it was OK…” – reveals the white fear and fragility related to social change that is at the heart of this issue.

It is also important to understand, however, the extent to which the legacy of blackface minstrelsy has historically been sanitized – even normalized – by alarming gaps in the way we learn about American history and culture from a very early age, particularly in music education. While few music educators would ever condone blackface, countless teachers, choir and band directors, and music publishers continue to teach and print the songs associated with 19th century minstrel performance. Indeed, minstrel songs represent a significant part of the repertoire associated with early childhood and elementary-level music education. A well-known, beloved song like “Shoo Fly,” for instance, is frequently mischaracterized as a children’s song or an “American Folk Song” (as in this children’s vocal arrangement by Greg Gilpin from music publishing house, Alfred). In reality, it was most likely composed by noted minstrel performer and songwriter, T. Brigham Bishop, and was popularized by Bryant’s Minstrels in 1869. While modern versions of the song typically omit the explicitly racist verses, Bishop’s original circles around the fetishization of black bodies that typified minstrel songs, including references to skin colored dark by “[mo]’lasses” spilled by angels and noses enlarged by a stinging fly.

Most common in this repertoire, however, is the music of celebrated American composer, Stephen Foster. Songs like “Camptown Races,” (included in John O’Reilly and Mark Williams’s “Accent on Achievement” method book for beginner band, published by Alfred), “Oh, Susanna” (listed in “Essential Elements,” the method book published by Alfred’s major competitor, Hal Leonard), and “Old Folks at Home (Swanee River)” appear again and again in children’s music classes. Although Foster’s songs aren’t often as virulently racist as minstrel songs, his lyrics almost invariably traffic in caricatured, exaggerated speech patterns and other racist stereotypes. The lyrics printed in the original, 1850 edition of “Camptown Races” (subtitled “a favorite Ethiopian song” – a common descriptor for minstrel music) are replete with purposeful mispronunciations of words, meant to represent an African American dialect in a way intended to be both comedic and defective: “De Camptown ladies sing dis song,” and “Gwine to run all night! Gwine to run all day!”

In “Oh, Susanna,” first published in 1848, Foster used the same mode of racialized speech to help represent a comically stupid protagonist, another common minstrel trope designed to perform the presumed intellectual deficiency of African Americans for white audiences. The singer in “Oh, Susanna” offers, “It rain’d all night the day I left, the weather it was dry. / The sun so hot I froze to death, Susanna don’t you cry;” and later, “I jumped aboard de telegraph and trabbelled down de ribber / De [e]lectric fluid magnified and killed five Hundred Ni**er.”

Meanwhile, “Old Folks at Home,” which remains one of two official songs of the state of Florida (albeit with – as usual – revised, sanitized lyrics) tells the story of a slave, perhaps freed, perhaps escaped, “longing for de old plantation, and for de old folks at home.” Like so many minstrel songs, “Old Folks at Home” allows white listeners to reimagine slavery and the antebellum south as a subject worthy of nostalgia, a time when hardworking slaves were treated gently by kind masters, almost as if they were family. We continue to see the ways in which this insidious discourse infiltrates the popular consciousness, as when Megyn Kelly’s erstwhile Fox News colleague, Bill O’Reilly, insisted that the slaves who built the White House were “well-fed and had decent lodgings.”

And herein lies the real cultural work of the continued ubiquity of minstrel songs in childhood music repertoire: even with lyrics revised to disguise their original purpose, they allow Americans – especially white Americans – to construct false narratives about the history of slavery and race relations in the U.S. They are included in children’s music books partly for their simple, singable melodies, but primarily to ensure that the core corpus of American music education has the feel of being time-honored, traditional, and American, in celebration of a generations-old American musical and cultural legacy. As a result, white supremacy becomes the bedrock of American music education – one of the first places that children begin to encounter and enact their own cultural histories. If Megyn Kelly took music classes in school, no doubt she would have sung these same songs with her classmates, like so many of us have. Little wonder, then, that she, like so many of us, would have such a blind spot for the “awful,” “racist” history of blackface in this country.

Like the Confederate statues that are finally being torn down across the country, these songs belong in museums, not on pedestals. They should be subject to our scrutiny, not our admiration. It is long past time to revisit the ubiquity of minstrel songs in our schools. The minstrel music of Stephen Foster, T. Brigham Bishop and others, and its attendant legacy of blackface, absolutely have a place in the history of American music and culture, both as music per se, and as crucial lessons in the casual normalization of racism, white supremacy, and hate.

Shares