These are not good days for optimists. Even the most sunny-sided among us lately can’t help feeling the weight of so many recent tragedies, disappointments and just plain ugliness. Even people like Anne Lamott. And when the author of books with titles like “Small Victories: Spotting Improbable Moments of Grace” and “Hallelujah Anyway: Rediscovering Mercy” is feeling it, you know we’re in unchartered waters.

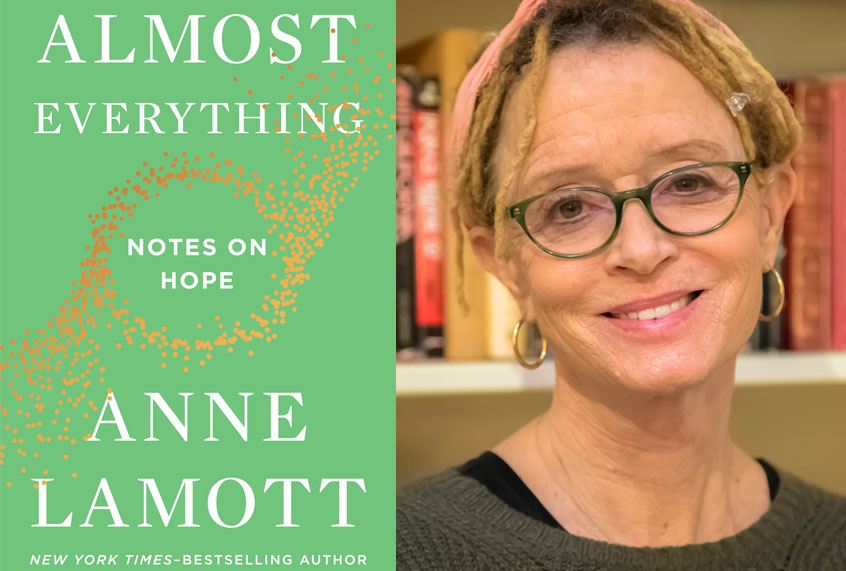

“I am stockpiling antibiotics for the apocalypse,” she writes in the opening of her newest book, “Almost Everything: Notes On Hope.” Yet in the darkest moments, there are often the greatest opportunities opportunities to see light.

“I have a lot of hope,” Lamott tells me. “It seems right now, the only book that anyone will want to read about is rage and exhaustion, and the dying of the ’50s in front of us, where these dinosaurs are in their last gasps smashing things with their big dinosaur tails.” But, she says, “I just had hope that if I said why I don’t feel defeated and how I still find joy and optimism, that it would resonate.”

“Almost Everything” mixes Lamott’s familiar blend of encouraging wisdom and hard won experience into a new balm for a wounded era. As the author juggles dog wrangling and last-minute preparations for a trip while she cheerfully submits to our phone interview, Lamott notes that “to look up, as a decision, keep looking up, not just at the mountains but up to the sky, at the plainest sky — let alone a starry galaxy of light — just to put on a better pair of glasses and notice how sweet people are being at the health food store, it can be proof of miracles. I just had 33 years of clean and sober, and that is not possible.”

Miracles, however, can’t obliterate calamity. “There’s a chapter in the book that begins ‘All truth is paradox’ and it’s true that these are the darkest, most devastating times,” Lamott said. “My grandson who’s nine right now will be 29 when the most optimistic catastrophic planet projections kick in. I’m ill imagining my 29-year-old son and nine-year-old grandson try to live in that world. And yet, there is just so much happening right now. The marches, the movements, the candidates. I am just so lifted up every day. I’m also learning to veer away from the deliberate manufactured misery when given a choice. It’s like eating food that you know is poison or that you’re allergic to. That’s another thing in the book — ‘no’ is a complete sentence. You have to make the decision to say no as a radical act.”

Another one is being happy, in spite of everything. “Joy is a habit,” she writes in her book. ” Lamott describes it as “like a middle finger in an Irish jig. It’s like, I will rise up against you and I’m going to go sit outside in the garden and read. I have a spiritual mentor, and her friend’s mom was taken to the convalescent home. At the front desk, the mom said, ‘I know this will be a beautiful room.’ The receptionist said, ‘How do you know?’ She said, ‘Because I decided it will be.'”

That decision-making is easier said that done, as anyone who’s ever been in a crappy space, emotionally or physically, can attest. It’s tough for Lamott too. “That is like so not me,” she said. “I’m so bitter, kind of judgmental, and cranky. But at the same time, that’s the choice we have. There’s a chapter on ‘Don’t Let Them Get You to Hate Them.’ I mean this in the paranoid sense of the word they, but they want us to hate and go crazy because then we’re controllable and we’ve lost our center. Then we lose our voice and we become them.”

“I think partly just to thwart them, I am working with the hate and I’m taking different path, all with 100 percent of the time being of service. I can watch some more MNSBC or I can go to St. Anthony’s and give an extra hand to do dishes after the lunch is served to the homeless. Then for a whole hour I am not an asshole,” she continued. “Someone said when I got sober that when they came into sobriety, ‘I was big shot and then I worked my way up to service.’ It’s going to give me hope that people are taking care of each other, because I’m taking care of someone. If I bring the hope, there will be hope.”

Hope and sorrow, two sides of the same coin. You kind of can’t get one without the other. As Lamott’s readers already know, she says that she was a sensitive child, and that her sensitivity still runs strong.

“A dog on the street with mange would upset me. I’d cry,” she said. “And Trump is a dog on the street with mange. This is the man who has never once been loved. Unloved and incredibly ignorant, narcissistic. I don’t go through the day feeling great about that. I go through the day with bouts of terror and rage and I feel completely betrayed. I am changed. But also, this terrible, terrible time in which we find ourselves in is also, from a recovery perspective, a giant bottom for the nation. Everybody I know who is clean and sober, it all began with catastrophic bottoms. You woke up and knew you were just completely doomed. I think the nation has hit a tragic bottom.”

“The thing that kills me is the kids at the border,” she said. “There’s no speck of religious truth that can help me with what’s happened to the kids in cages, at the border. But there is service. There is sending money to the lawyers who are representing them. There is prayer, which I believe changes things all day, every day. I am rage struck and I’m just livid, but I also can’t live there. I can also to try to deal with my own inner Donald Trump and not be part of the problem. I also believe that there’s salvation in story and the stories we’re telling each other. We take the action and the insight follows that there is nothing they can do to keep us down.”

When I ask Lamott, who has faced her own substance abuse and writes in “Almost Everything” about her son Sam’s recovery, how we can help each other without attempting to fix each other, she tells me, “everything in me wants to show up like a St. Bernard with a keg of Gatorade around its collar.”

But, she said, “This book is specifically about hope. People tell me they’re just going crazy and they feel very doomed. Sometimes they feel doomed because of Saudi Arabia or North Korea and sometimes they feel doomed because the girl down the street is anorexic, and they can’t save her. Not one single person in history saved another person from alcoholism or eating disorder.”

Instead, we have to save ourselves, show up for each other, and lead by that example.

“At some point,” she said, “with maturity or age, you stop believing your ideas are all good ideas. You realize they didn’t work last time, but you show up and you learn to listen better. The country is listening now. The American culture is an alcoholic male who is still drinking and trying to maintain and is going under and is hitting bottom.”

“This is a blessing I see arising from the devastating bottom of Trump’s presidency,” she added. “When you go to these marches, it’s young women in community and it’s women in their twenties and boy, they’re raring to go. What they’re learning at every march is that this work of showing up in service will heal them.”

Lamott knows that’s a tall order. “How will you do the self-care so that you’re giving from a place of being filled and feeling nourished with health and food, comfort and love?” she asks. “How do you not give from a place of deprivation and going hungry as we were raised to do it, as all women are raised to do? How do you find the balance between self-care and self-respect and pouring yourself into the community of the poor and the suffering and the kids at the border and the kids being shot at their school?”

“Well,” Lamott said, perhaps inevitably, “you do it bird by bird.”