Missouri is rushing to retrain thousands of poll workers just days ahead of the midterm election because of a new court ruling that forced changes to the state’s voter ID law.

The law, enacted in June 2017, said that voters could provide a non-photo ID at the polls, such as a utility bill or voter registration card, and sign an affidavit in order to vote. But on Oct. 23, just two weeks before Election Day, a decision by Missouri Circuit Judge Richard Callahan prohibited local election authorities from requiring voters to sign an affidavit, effectively making a non-photo ID adequate for voting on a regular ballot.

Now, election offices statewide are scrambling to retrain poll workers in the new procedures, and officials expressed uncertainty about whether poll workers will grasp the legal changes.

“As far as poll workers go, that’s the toughest nut to crack because they have been trained already,” said Eric Fey, the Democratic director of elections for St. Louis County, the state’s largest. “We know there will be some poll workers who don’t get it on Election Day, and we’ll deal with that when the time comes.”

Because Missouri offers no early voting or no-excuse absentee voting, the vast majority of ballots in the state’s highly competitive Senate race, as well as other local races, will be cast on a single day. With turnout expected to be high nationwide, any poll worker errors could have large consequences.

Complicating matters further, the Missouri statewide ballot — 19 inches long and double-sided — is unusually complex. The ballot in St. Louis County is the longest in its history. In Jackson County, the Republican director for the county’s election board, Tammy Brown, said some in-person absentee ballots took voters 20 to 40 minutes to complete.

Long lines at polling places are already anticipated in many key counties. The additional risk posed by the rule change is that ill-trained poll workers could cause waits to grow even longer as officials try to clear up confusion among workers and voters at the polls.

Fey said he hires 3,500 poll workers — also called election judges in Missouri — each election and begins training them seven weeks before Election Day. The ruling on the ID law came down after training had been completed, and the county was forced to dispatch mail, emails, text messages and robocalls to inform workers of the legal change ahead of Election Day.

The director of elections in Platte County, Chris Hershey, said receiving the ruling right before Election Day has “definitely caused some uncertainty.” The Platte County Board of Elections commissioners explained the change to poll workers in a memo with an image of the updated poll book screen attached. The county of about 90,000 people did not have the ability to order new signs omitting the overruled language, so it covered them with construction paper and tape.

“I don’t expect it to be a big issue with voters. Most of them are in the habit of bringing their driver’s license, and they can vote regardless,” Hershey said. “I feel like the poll workers might be the hitch in the system, but we’re getting them up to speed.”

In Cape Girardeau, County Clerk Kara Clark Summers opted for an emergency 30-minute training for the 250 election judges working on Election Day because she was worried about people misinterpreting a written explanation.

“The last two weeks are critical,” Summers said. “We thought about sending out a memo with the new ruling, but everyone reads things differently. I want them to hear it from me directly so that everyone is comfortable going to the polls and working. There’s already confusion surrounding this law, and we want the people on the front lines to be ready.”

Not wanting to waste funds on reprinting election signs explaining the law, her team took markers to the old, laminated version, crossing out phrases and sentences referring to an old requirement for an affidavit.

Some counties had to unpack voter signs and e-poll books that were ready for transportation to polling locations, breaking the security seals and reprogramming the software. The move “set them back significantly” as Election Day preparations loom, Fey said.

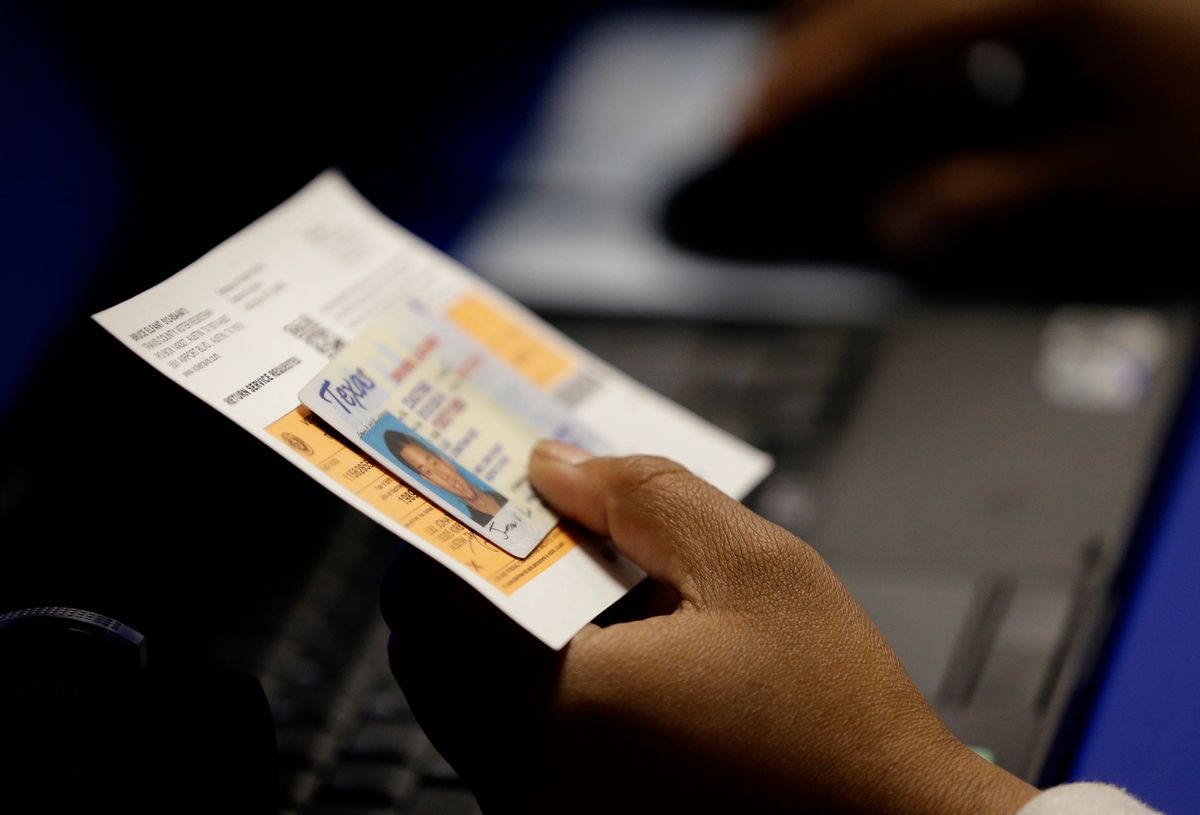

Late changes to election laws have caused widespread confusion among voters and poll workers in previous elections. A 2017 ProPublica storyfound that a late change in Texas’ voter ID laws puzzled poll workers and sparked hundreds of Election Day complaints.

In addition to a polarized and amped up electorate, voter turnout seems likely to be high in Missouri because of a toss-up Senate race between incumbent Democrat Claire McCaskill and Republican Josh Hawley — a race that might decide which party controls the Senate, as well as eight House races.

“All signs point to a high-turnout election,” said Michael McDonald, a professor researching elections at the University of Florida. “The fact that Missouri doesn’t have generous early voting options means that many voters are going to be casting their ballots on Election Day. I think it would be prudent of election officials to prepare for a high-turnout election, not a business-as-usual election.”

Calls made to Missouri election offices found at least one doubting the likelihood of high turnout. St. Louis County’s Fey said there was little indication that his county would experience a higher-than-normal rush to the polls. He said voter registration and absentee requests remained steady across the county until the final week, and the office did nothing to boost poll worker numbers in order to accommodate the potentially heavy turnout. But, he said, “You never know on Election Day.”

About 230 miles west in Jackson County, home to Kansas City and Independence, residents seem more set than usual on voting in the midterms. Voters began calling the local elections office about absentee voting before ballots were even printed, and voter registration was so heavy that local officials were adding voters to the rolls for weeks after registration closed. To accommodate heavy turnout, the county hired up to four extra poll workers per location.

“I think we will have a pretty strong turnout; it’ll likely exceed any midterm election in the past. We’re just busy, busy,” Brown said. “Everyone is just so energized. Our phones never stop ringing. You hang up one call and it’s immediately another.”

Most states use a period of early voting to find and solve problems in their planning or materials, and to move resources where they’re needed to shorten wait times. But with only a single day of voting, Missouri counties must rely entirely on their own planning acumen.

A few small Missouri counties, such as Lincoln, train poll workers a few days before Election Day. The election supervisor for the region of about 56,000 people, Mike Kreuger, said his team always waits until as close to the election as possible, so poll workers aren’t given confusing instructions. A few voters have walked into the office and asked for clarification on the ruling, but for the most part, the “last-minute updates” are occurring behind the scenes.

“The voter ID law was a little confusing the way it was written,” Kreuger said. “I hope everyone can be patient and understand that we’re doing the best we can.”

Shares