What happened in the midterms was seismic. We had a blue tide electorate that was younger and more diverse that swept away dozens of incumbent House Republicans. At least four, perhaps five congressional districts in my state of New Jersey flipped from GOP control to the Democrats, leaving just one Republican in the state's 12-member delegation.

You would have to go back to 1966 to find a midterm when 49 percent of eligible voters bothered to turn out like they did on Nov. 6. And if Democrats want 2018 to be a prelude to continued electoral success in 2020, they need to deliver things that are tangible for the people that elected them.

For the new Democratic House that will be tough to do with Donald Trump in the White House and the Republicans still riding roughshod in the U.S. Senate.

But in New Jersey, where the Democrats run the show, they don’t have that excuse. So they need to get over the kind of internecine party warfare we saw over the state budget where the public welfare is trumped by personality conflicts amongst the leadership.

That budget imbroglio revealed a real disconnect between the economic misery experienced by the million or so New Jersey families that struggle week to week to make ends meet and the professional political class in Trenton that supposedly represents them.

It’s not quite like Marie Antoinette and the "Let them eat cake" sensibility, but it's close. You just don’t get the sense that politicians grasp that there’s a real crisis of affordability in the state that’s not abstract but weighing on daily life and hitting working-class families with children the hardest.

How else do we explain the hemming and hawing from the Democratic legislative leadership about when they will get around to passing a bill to gradually boost the minimum wage to $15 an hour?

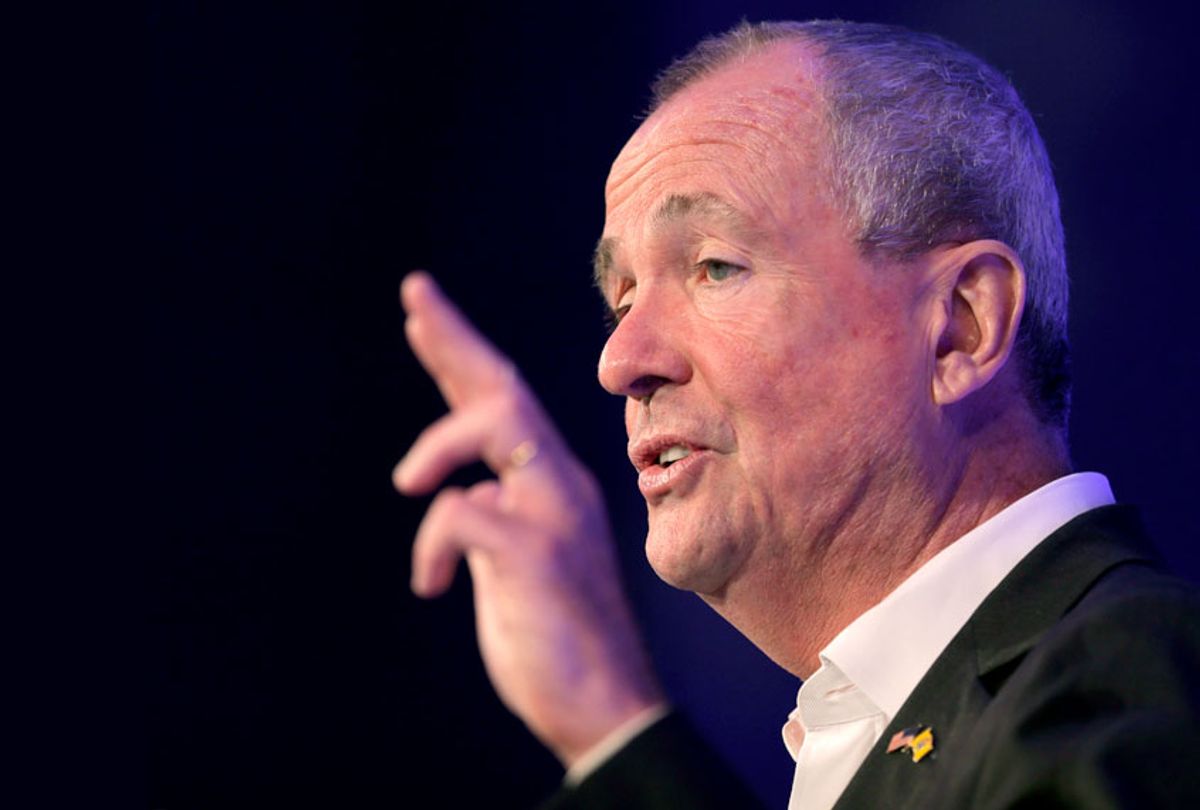

This was a top campaign priority of Gov. Phil Murphy, yet as we close in on the first year of his tenure, the former Goldman Sachs executive has yet to produce on this score.

He did tweet that it was “indefensible” that New Jersey’s minimum wage, accounting for the local cost of living, is “the fifth-most insufficient in the nation.”

Assemblyman Craig Coughlin, D-Middlesex, said on WCTC radio that he is aiming to have a bill that the Assembly can vote on by December or early next year. “If it doesn’t get done at the Dec. 17 voting session, then it will be done right after the New Year, probably at the first voting session in January,” he said, according to NJ.Com. “At least that’s my goal as of right now.”

And bringing up the rear, Senate Majority Leader Stephen Sweeney, D-Gloucester, said he backs the concept but is looking to cut teenagers and farmworkers out of the $15-an-hour "promised land."

New Jersey’s elected leaders are even lagging behind corporate America. Amazon just announced it was raising its minimum wage to $15 an hour for its 16,000 New Jersey employees.

“We listened to our critics, thought hard about what we wanted to do, and decided we want to lead,” Jeff Bezos, Amazon founder and CEO, said in a statement. “We’re excited about this change and encourage our competitors and other large employers to join us.”

Back in 2013, New Jersey voters approved a referendum on a constitutional amendment that raised the minimum wage from $7.25 an hour to $8.25 and linked further increases to the Consumer Price Index. That will translate on Jan. 1, 2019, to a $8.85 minimum wage thanks to a 25-cent increase.

But, according to an analysis by New Jersey Policy Perspectives, a New Jersey family with one child needs a wage of $20.07 an hour to make ends meet. According to the nonprofit think tank, there’s quite a range between the state’s 21 counties — from $17.32 an hour for workers in Camden to $22.26 in Hunterdon.

Boosting the minimum wage “would inject $3.9 billion into the state’s economy and help over 1 million workers better afford their needs,” according to NJPP. “Today, there is no region of the state where a single worker with no children can afford basic necessities while making less than $15 per hour. The costs of transportation, food and rent are simply too high for a minimum wage worker to afford without suffering in poverty.”

Recently, the United Way released its annual update of the so-called ALICE population -- that is, asset-limited, income-constrained but employed -- who struggle week to week.

In the more than 200,000 households in New Jersey that are headed by a woman, 37 percent live below poverty while 39 percent fit the ALICE criteria, leaving just 23 percent that are not struggling week to week. Are we going to continue to nickel and dime these folks?

According to the latest data, 38 percent of New Jersey’s households live either below the poverty line or in the ALICE cohort. Between 2010 and 2016, poverty remained relatively stable at the 10 percent level. But over that same period the number of New Jersey ALICE families went from 24 to 28 percent, as wages stayed stagnant but costs for basics rose.

“The cost of basic needs outpaced the rate of inflation and wage growth, rising 16 percent to $26,640 annually for a single adult and 28 percent to $74,748 for a family of four with an infant and preschooler,” according to a United Way press release. “Meanwhile, median earnings only increased by 12 percent during the same period. The result is that the number of ALICE households grew from 754,664 in 2010 to 895,879 in 2016, a 19 percent increase and nearly triple the number in poverty.”

In Cumberland County, the United Way found close to two-thirds of households either living below the poverty line or in the ALICE cohort. In Essex County, more than half of all households are struggling. In Salem, Ocean, Atlantic and Passaic counties, close to half of all families are just getting by.

This is a crisis requiring immediate attention, not posturing as usual.

Shares