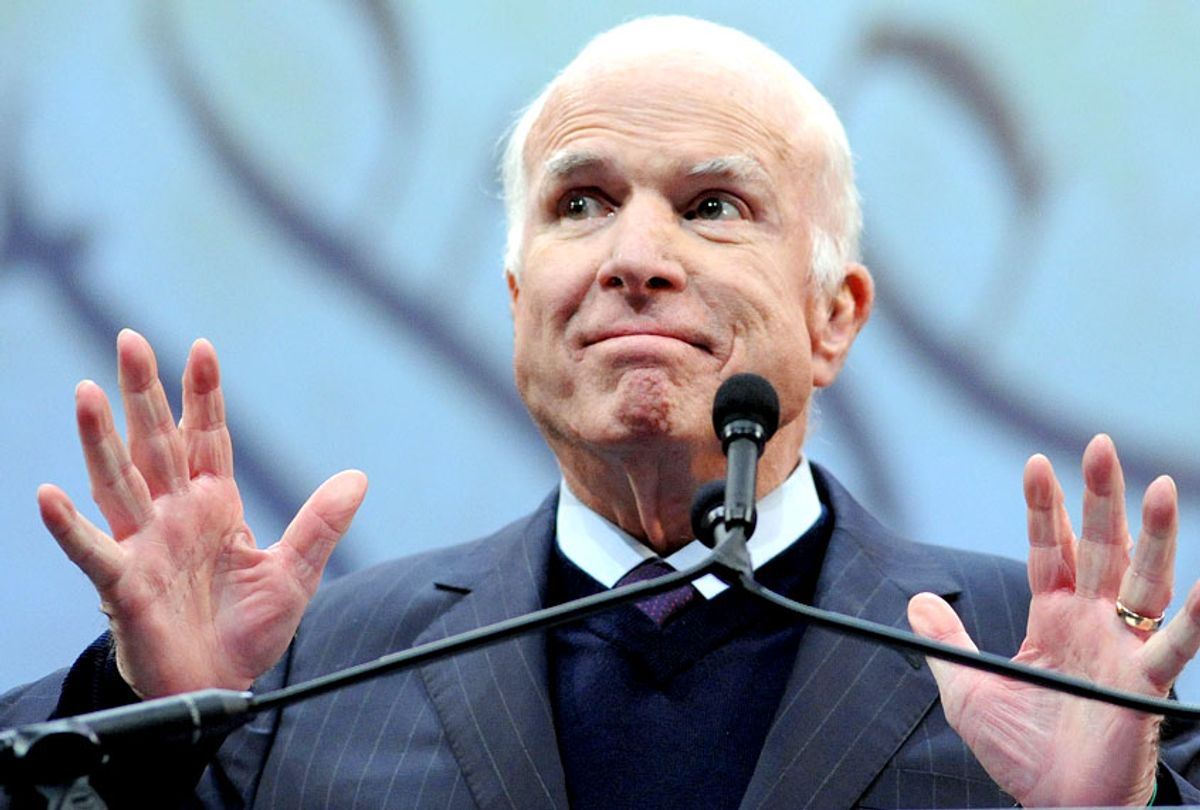

Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Jason Lewis claims that “The Republican Party lost its House majority on July 28, 2017, when Sen. John McCain ended the party’s seven-year quest to repeal Obamacare.” Up to then, he says, the Republican leadership had done “an admirable job herding cats,” culminating in the passage by the House (on their second try) of the American Health Care Act (AHCA). Then McCain blew it all in the Senate.

Nonsense. The cat-herders who wrote the AHCA were themselves to blame. From the beginning, the AHCA had no credibility in tackling the problem that ranks No. 1 in the health care concerns of voters: Guaranteeing affordable access to health care for the millions of Americans with pre-existing conditions.

Here is what really happened.

The AHCA's promise of high-risk pools was a sham

Lewis claims that the AHCA would have covered the most difficult-to-insure with $138 billion worth of high-risk pools. Yes, in principle, high-risk pools are one potential way to protect people with pre-existing conditions. But if we understand the way they work, it is easy to see that the token version offered by the AHCA was never more than a sham.

Boosters of the AHCA talked up high-risk pools as if it would be easy to offer them to a small sliver of the population — just 5 or 10 percent — and let everyone else pay their own way. Unfortunately, given that the top 10 percent of individuals account for more than half of health care spending, it would not be easy at all.

In a study for the Commonwealth Foundation, Jean P. Hall of the University of Kansas calculates that the net cost to the federal budget of a fully-funded national high-risk pool would be $178 billion per year. That assumes the pools would cover 13.7 million people with chronic conditions, which is less than 5 percent of the population. Each of them would pay a premium of $7,000 per year and have average medical costs of $20,000 per year, requiring a subsidy of $13,000.

The AHCA never came close to providing that kind of money. The $138 billion that Lewis cites was not an annual figure, but rather, was spread over many years. In reality, the proposed Patient and State Stability Fund would have given states just $10 billion per year, plus a little start-up money, to experiment with high-risk pools if they wanted to. The law would also have allowed them to spend the money on other things, but even if they spent it all on high-risk pools, it would have come to just $728 a year for each of 13.7 million medically eligible individuals — or enough to cover Hall’s estimated $13,000 per year average subsidy for fewer than 750,000 out of 13.7 million medically eligible candidates.

The AHCA and the death spiral

What did the AHCA have to offer to healthier people who are not qualified for the high-risk pools? Lewis says that it would have evened the playing field by offering refundable tax credits anyone could use to buy individual plans, and by expanding tax-deferred health savings accounts to help cover deductibles, copayments and over-the-counter expenses. But more likely, it would instead have caused the AHCA to enter a death spiral that was only narrowly averted by John McCain’s infamous thumbs-down.

Just how does this notorious “death spiral” work? Start with a basic truth: A private insurer can profitably offer health care coverage to a pool of customers only if it can find a premium that is low enough to be affordable, yet high enough to cover expected claims and administrative costs, with enough left over to keep shareholders happy. In order for that to happen, the pool of customers must contain enough healthy people to keep claims and premiums low.

If premiums are too high, healthy people begin to drop out and take their chances covering their own medical costs. Fewer healthy people in the pool raises the claims per member — a process that economists call adverse selection. Soon, premiums have to be raised further. That causes still more people to drop out until only the sickest people are left in the pool. At that point the insurers themselves pull out, and the death spiral is complete.

The AHCA did include features that would have tended to enlarge the pool of those seeking insurance in the individual market. One was a repeal of the mandate for larger employers to provide coverage, which would have pushed many workers into the individual market. In addition, rule changes would have made some low-income families or individuals ineligible for Medicare. On the face of it, a larger insurance pool would make the system more stable. However, that would be true only if the individuals who actually purchased individual policies after being displaced from employer coverage or Medicaid were of average or better health.

Instead, most of those who lost other coverage would have been of lower than average income. Medicaid was already limited to households below or just above the poverty line, and companies would have been more likely to stop health care coverage for their marginal employees than for their best workers. Lower-income households not only tend to have more health problems, but are more likely to forego coverage unless they are very sick. As a result, the hoped-for enlargement and stabilization of the individual insurance pool would never have materialized.

John McCain deserves a reward from the GOP, not abuse

If Republicans were honest about the effect of McCain’s “Nay” on health care, they would be offering him a posthumous medal for distinguished service, not heaping on the abuse. If the AHCA had passed, millions would have lost insurance coverage. Instead of just talking about what the Republicans tried to do, Democrats would then have been able to point to the effects of a law they had actually passed. The blue wave that washed away the Republican House majority would then have been a tsunami. Not just the House, but the Senate would have been flipped for a generation.

I’ll give Lewis credit for one thing, though: He’s dead right when he writes that because the AHCA didn’t pass, we’ll never fully succeed in refuting the lies about it.

Shares