Despite record turnout and a historic shift in power in Congress, the 2018 midterm elections represent a dangerous moment for the future of American democracy. From Georgia to Kansas to North Carolina, this election has been marred by a concerted effort to rig our democracy and suppress the voices of communities of color. From voter purges to gerrymandering to openly racialized intimidation attacks, conservatives have continued to escalate their attempts to entrench political power by dismantling democratic institutions.

This is not the first time the country has faced this kind of assault on both democracy and multi-racial political power. We have done so twice before: first in the Reconstruction era that followed the Civil War, and second in the civil rights movement battle to dismantle Jim Crow. These previous experiences underscore the scope of the challenge for us today. To rebuild democracy and ensure it works for all us, we will have to do more than win elections; we need to radically transform our underlying democratic institutions.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Republicans and abolitionists in Congress launched an ambitious project of Reconstruction aiming to dismantle the legacy of slavery and racial hierarchy. These efforts led to the adoption of the radical Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution: the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery; the 14th Amendment securing the privileges and immunities of citizenship including rights of equal protection and due process for all persons; and the 15th Amendment prohibiting states from disenfranchising voters on basis of race. It would take another several decades for these constitutional provisions to include women.

For a brief moment, Reconstruction promised a radically new, inclusive democracy. Protected by new civil rights legislation, including the Enforcement Acts of 1870 and 1871, which criminalized efforts to violate civil rights and suppress the vote, African-Americans turned out to vote in huge numbers, electing hundreds of African-American representatives at the state and local level. Populist reform movements briefly allied with black communities. But the backlash to this potential multiracial democracy was swift and furious.

In 1873, armed former Confederates stormed the courthouse in Colfax, Louisiana, overthrowing the results of a county election that was handily won by African-Americans, and slaughtering more than 100 black people who had come to defend the courthouse and the certification of the election results. Seventy-three white men were charged under the Enforcement Act, but the Supreme Court overturned their convictions in the case U.S. v. Cruikshank, clearing the path to the racist brutality that would characterize the Jim Crow era. Racial and political inclusion required new legal enforcement tools — offered by the amendments and the Enforcement Acts — to become a reality; the nullification of these legal tools by the Supreme Court and racial violence effectively reversed the gains of Reconstruction.

The attempt to dismantle Jim Crow — the stinging web of laws and practices that enforced racial segregation — similarly took place not only through the powerful organizing and resistance of the civil rights movement. This “Second Reconstruction” ultimately required the creation of new legal regimes to enforce the ideals of political and racial inclusion. The civil rights movement codified its vision through the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. These statutes created new federal enforcement powers, backed by the powers of the federal government and the Department of Justice.

But as with the first Reconstruction, these gains have been gradually nullified, though by more subtle and less visible means. The rise of mass incarceration and the persistence of felon disenfranchisement have created a modern-day equivalent of Jim Crow. More recently the Supreme Court has bit by bit dismantled the protections of the Voting Rights Act and the 14th Amendment right to vote. Decisions like the 2008 Crawford v. Marion County Election Board case upheld voter ID laws that have since been weaponized to suppress voters. In 2013, the Court struck down the Voting Rights Act formula requiring districts with a history of racial voter discrimination to preclear their voting administration policies with the Department of Justice. And most infamously, the Supreme Court opened the floodgates of corporate money in politics through its decision in Citizens United.

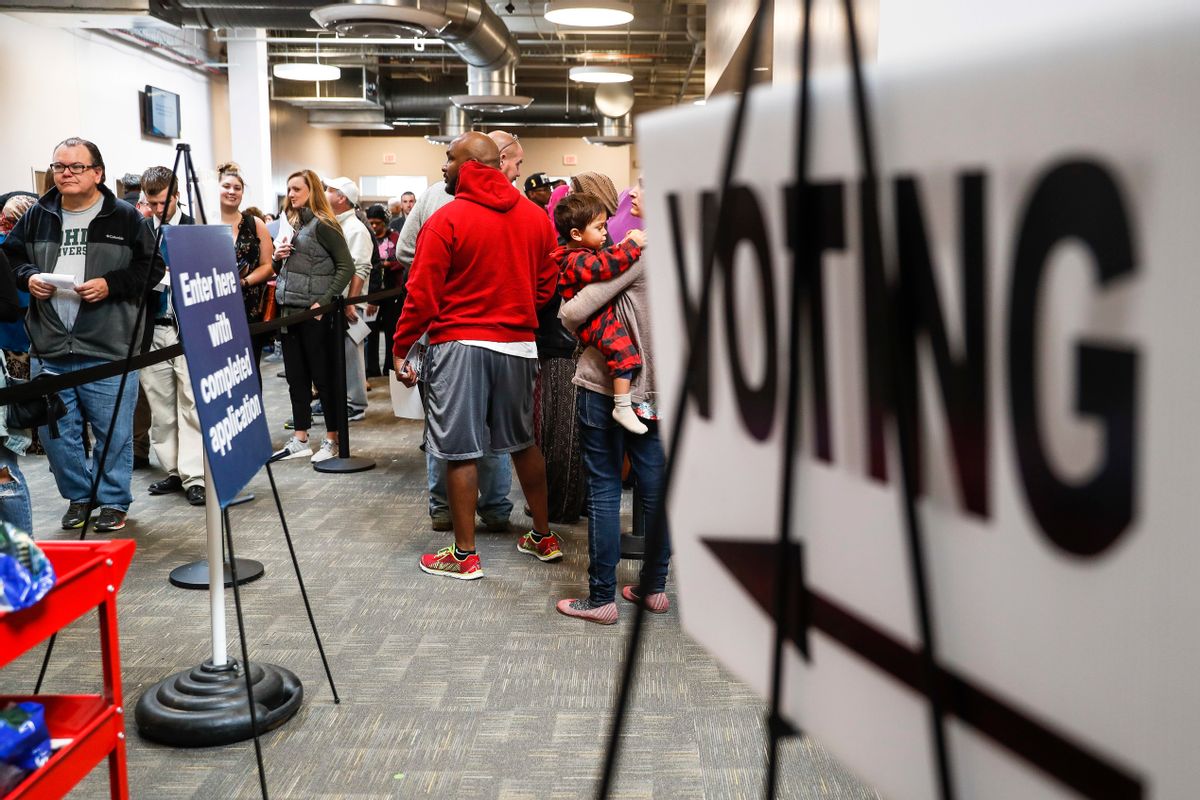

Like Cruikshank before them, these cases amount to a judicial green light for a wave of suppression aimed at silencing the political voice of communities of color. In Wisconsin, hundreds of thousands of voters were purged and excluded from participating in 2016, where the margin of Trump’s surprise victory in that state was a mere 23,000 votes. In the recent midterms, Brian Kemp’s bare electoral victory over Stacey Abrams is a glaring case of electoral rigging: as secretary of state, Kemp closed down polling booths in predominantly African-American districts, and through his “exact match” program — proven to be highly inaccurate — tried to exclude an estimated 50,000 or more voters, largely from communities of color. States like North Carolina, Ohio, Kansas and many more have faced similar efforts to purge and suppress voters in order to secure political power for conservative politicians.

In the face of such intentional damage to the democratic process, voting in unprecedented numbers may not be enough, as the recent elections revealed. We may need — indeed, we may be in the beginning of — a new Reconstruction, rebuilding a new, inclusive democracy with equity for all.

What would a new Reconstruction look like? It could expand, rather than restrict, the electorate by using information already on file with government agencies to automatically add eligible people to the voter rolls. It could enable people to register on Election Day, and vote by mail, online or beginning weeks before Election Day, as many states already do. It could increase the power of regular citizens by using public funds to match small political donations, so candidates can listen to their potential constituents rather than chasing dollars from corporations and mega-donors. An inclusive democracy could restore voting rights to persons previously convicted of felonies, as Florida just voted to do for 1.4 million of its citizens. It could create congressional districts based on population and not partisanship.

Through a new Reconstruction, we can also restore a democratic public sphere. Unravel the knots of corporate power created by Citizens United and such monopolistic empires as the right-wing Fox and Sinclair communications companies, which control the only media sources available to large swaths of America, and regulate mammoth online platforms like Facebook and Twitter, which enable the disinformation and hate speech that corrode public trust and institutions. Strike down so-called “right to work” laws to correct the power imbalance between employers and workers that has resulted in vast economic growth at the top but wage stagnation or worse at the lower end of the economic ladder dominated by people of color and women.

While these actions are unlikely to pass under a Trump administration, many can be taken by states — potentially setting up future federal activity. And most will elevate the democratic access of people of color who have been historically and continually excised from the body politic. As the most diverse generation in American history comes of age, we must build the legal and constitutional institutions needed to ensure an inclusive democracy that functions for us all.

Shares