This past January, a woman was walking along a road in Tumwater, Washington when a man pulled her into the woods and raped her. This rape might not have happened had police quickly processed evidence from the sexual assault exam — or “rape kit”— from another Tumwater rape the previous summer. But because it took nearly six months for experts to analyze and match the DNA, the suspect had the opportunity to attack again.

It's not uncommon. In order to have the best possible chance at finding and prosecuting an attacker, victims must submit to an invasive exam as soon as possible, because the evidence quickly degrades. Many survivors say they hope the evidence will help prevent another sexual assault. But in reality, there is a significant backlog, and samples can sit untested for weeks, months, or even years. In the United States alone, an estimated 225,000 rape kits await analysis. And the backlog isn’t only unjust, it’s expensive: A 2018 study from researchers at Stanford University estimates the cost of each assault to both the victim and society at $435,419.

Advocates have long pressed to end this backlog. “It sounds ridiculous that we can send someone to the moon, but how long does it take to test a rape kit? Come on,” says Ilse Knecht, director of policy and advocacy at the Joyful Heart Foundation, a national nonprofit, founded by actress Mariska Hargitay, that focuses on sexual assault, domestic violence, and child abuse.

Such complaints are not new, but advances in forensic DNA technology and robotics suggest that the rape kit backlog may finally be improving. A technique optimized by criminalists at the Oakland Police Department in California, for example, makes it faster and easier to differentiate between the attacker’s and victim’s cells. And thanks, in part, to new robotic equipment, Ohio officials recently processed nearly 14,000 backlogged rape kits in seven years and identified more than 300 serial rapists.

The improved technology has arrived at a crucial time, as advocacy initiatives like Joyful Heart’s End The Backlog — which works to eliminate the U.S.’s backlog through research, awareness, and policy reform — are spurring legislative changes and pushing law enforcement to test old evidence. At the same time, the new tools are creating mountains of genetic information, and without people to enter all of that data into relevant databases, write reports, and search for perpetrators, more efficient processing may simply move the backlog downstream. Activists also argue that new processing techniques will do little to correct biases in which rape kits get speedy processing, and which don't.

Still, the improvements have activists hopeful that the new technology will go a long way toward reversing longstanding injustices.

“It’s undeniable now that the right thing to do is to test rape kits,” Knecht said. “We are taking really dangerous people off the streets by doing so.”

* * *

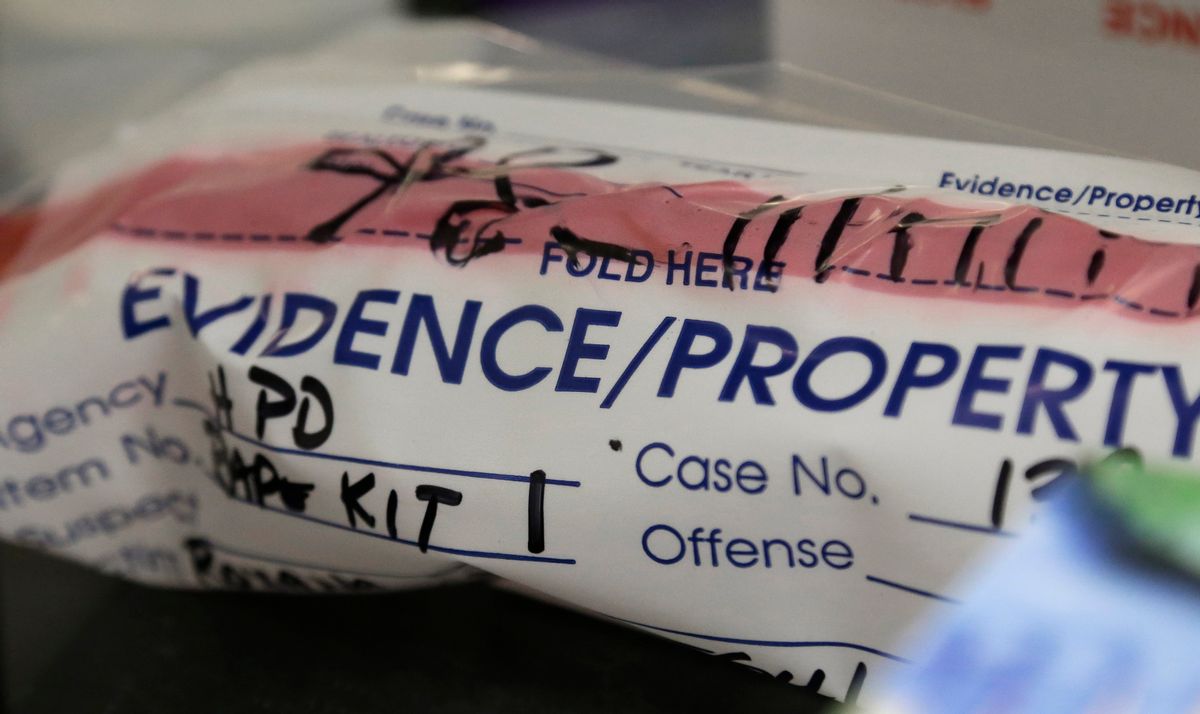

In the 1970s, Chicago police sergeant Louis Vitullo and activist Marty Goddard developed the first rape kits. The kits have remained more or less the same since then: A box, vials, swabs, and bags. A medical professional swabs the skin, mouth, anus, and genitalia; scrapes under fingernails; collects clothing; and combs though hair, searching for anything that could point to the attacker. Then, the examiner packs up the evidence in a box to store at the hospital or send to a police station or a lab. There, a technician examines the evidence, which today includes extracting DNA to find genetic clues that may help law enforcement identify potential suspects.

Thanks to greater public awareness, legislation, and funding, there has been an uptick in research on rape kit technology. In the last eight years, scientific papers on rape kits have increased by roughly 60 percent, and the focus has shifted from protocols, policy, and consent, to methods for finding, purifying, and identifying DNA — especially DNA in sperm.

For rape kits, one of the most critical and time-intensive steps is separating DNA from the attacker and the victim. Because of this, scientists such as Helena Wong and Jennifer Mihalovich, both criminalists at the Oakland Police Department in California, often focus on developing methods that help automate this process without diminishing the accuracy of the results.

“You have epithelial cells — those are the cells that line the mouth, the vagina, and the rectum — and then you have sperm,” Mihalovich says. “And we know when we're looking at that evidence that they're going to be mixed together.”

To isolate the attacker’s contribution, analysts typically add enzymes to the mixture that break apart all but the sperm heads, which are protected by a robust cell wall. In the conventional process, the analyst separates these components with a centrifuge, which spins so fast that the liquid components press against the container wall and separate by size and density like a supercharged top-loading washing machine. The process takes several rounds, but even then, some non-sperm DNA gets left behind, muddying the results.

Instead of that time-consuming process, Wong and Mihalovich use an enzyme that can “chew up all of the epithelial cell DNA and not touch the sperm because they have that hardy cell wall,” Mihalovich says. Finally, when all the epithelial DNA is gone, the analysts add another chemical that breaks apart the sperm cell, so they can get at that prize sperm DNA.

This “selective degradation” process is well-suited for automation. “For our sexual assault cases, we can do up to 96 samples in eight hours,” Mihalovich says. Without the improvements, “We would need to have six scientists doing that manually.” Plus, while the robot is working, Wong says she is free to do other things.

So far, the method is working — it’s allowed the team to process 243 rape kits in less than a year, eliminating the lab’s rape kit backlog. The Oakland team says they have also been assisting other Bay Area labs in the technique, including those in Contra Costa and Alameda counties.

University of Connecticut genome scientist Bo Reese finds the work interesting and well-done. “What’s nice is they centered it around the automated liquid handling robots,” she says, “all of which are small enough and cheap enough that most labs will have them.”

And analysts are finding other ways to streamline DNA analysis for rape kits. In a paper published in July in Forensic Science International: Genetics, scientists at The George Washington University describe an approach for confirming sperm in a sample with antibodies that seek out and attach to sperm cells. It requires only a tiny sample of evidence and no washes, purifications, or separations between steps, which means that, as with the Oakland team’s approach, it may be possible to combine it with robotics to analyze large batches at once.

It’s not just sperm that can out a sexual criminal. Criminalists can identify attackers with DNA left in the survivor’s saliva if tested early enough, and even imprints of skin. Automation technology is improving too. Soon, Reese says some labs will be able to process as many as hundreds of thousands of samples at once.

These advances are crucial. In 2017, an independent research firm hired by the U.S. Department of Justice found that inefficient lab techniques were a key driver of the backlog. The report also confirms that prioritizing speedy rape kit processing is important to closing cases. Reese also sees them as an important step forward. “The technology advances, in my opinion, are wonderful.”

* * *

Still, activists argue that science alone can’t solve all the problems with rape kits. Rather, they argue, the backlog is a result of a complex interplay among technology, policy, history, and bias. In January, a study of rape kit processing in Detroit published by researchers at Michigan State University and Harder and Company Community Research found that while lack of resources contributed to the significant backlog, gender, race, and socio-economic stereotypes were also strongly in play. Police were less likely to test kits of women with low social status because of the false assumption that they were less trustworthy as witnesses, the researchers found. Police also often assumed rape victims were involved in sex work, the researchers found, and tried to “‘nudge them’ out of the system and discourage them from continued pursuit of their report.”

In some cases, processing advances might just be creating a new backlog as the analysts who interpret the data get inundated with reports. “Imagine you're at your desk,” Reese says, “and instead of getting one every couple of days, you now get 96 all at once.”

Employing people to analyze the reports also takes money, as does robotic lab equipment, tracking systems, and training for nurse examiners and forensic analysts. This fall, Louisiana State University won a $1.3 million grant from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to train 140 sexual assault nurses, putting the per-nurse cost at around $9,300. The automated machine that Wong and Mihalovich used for their sperm samples runs at least $65,000 for a new model. And although states can request federal grant money, some jurisdictions aren’t willing to take the time or make the investment.

According to End the Backlog, states like Nebraska, Wyoming, and South Carolina currently have no inventory of untested rape kits, no mandate or earmarked statewide funding to test them, and no way for victims to learn where their kit is in the process. In local reports, law enforcement officials in South Carolina and Nebraska cite uncooperative victims, known suspects, and guilty pleas as potential reasons not to process a rape kit, despite evidence that mandated testing has helped to solve cold cases. Without policy directives or funds to address the backlog, or even numbers on how many and how long unprocessed kits wait, analysts have limited ability to adopt more efficient technologies.

Despite these barriers, science and technology are helping motivated states including Oregon, Texas, and Hawaii make real progress. In the end, anything that helps analysts turn the kit into usable information is a win — particularly in cases like the assault in Tumwater, Washington, where a faster analysis could have prevented another attack.

“Each single one of these kits represents a survivor who has gone through a terrible experience," Knecht says, "and then has done everything that society asked them to do."

Jenny Morber works a freelance science journalist on an island near Seattle. Her work has appeared in Popular Science, Discover, Glamour, and National Geographic, among other publications.

Shares