In the wake of the national nightmare known as the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation hearings, we have seen an avalanche of proposals by Supreme Court watchers, pundits and experts with the express purposes of weakening the court and trying to turn down the political temperature of future confirmation battles. Most of these court-altering suggestions have come, not surprisingly, from the left. After all, as many have observed, the nation’s highest court is likely to be a conservative bulwark for the next 20 to 40 years. These proposals include ending life tenure, reforming recusal practices, requiring a supermajority vote to overturn laws and even stripping the Supreme Court of jurisdiction over various controversial areas of constitutional law.

But weakening the court because of its current political makeup is looking for answers in all the wrong places. This country needs to restructure the U.S. Supreme Court not because it is too conservative, too liberal or even too moderate. We need to change the court because it wields far too much power and influence regardless of which political side benefits from its decisions. In 2012, I made many of the suggestions listed above in the final chapter of my book “Supreme Myths: Why the Supreme Court is not a Court and its Justices are not Judges.” At the time, most liberals strongly opposed these ideas while conservatives were slightly, though not dramatically, more sympathetic. Now the urge to reform comes mostly from the left -- but not for the right reasons.

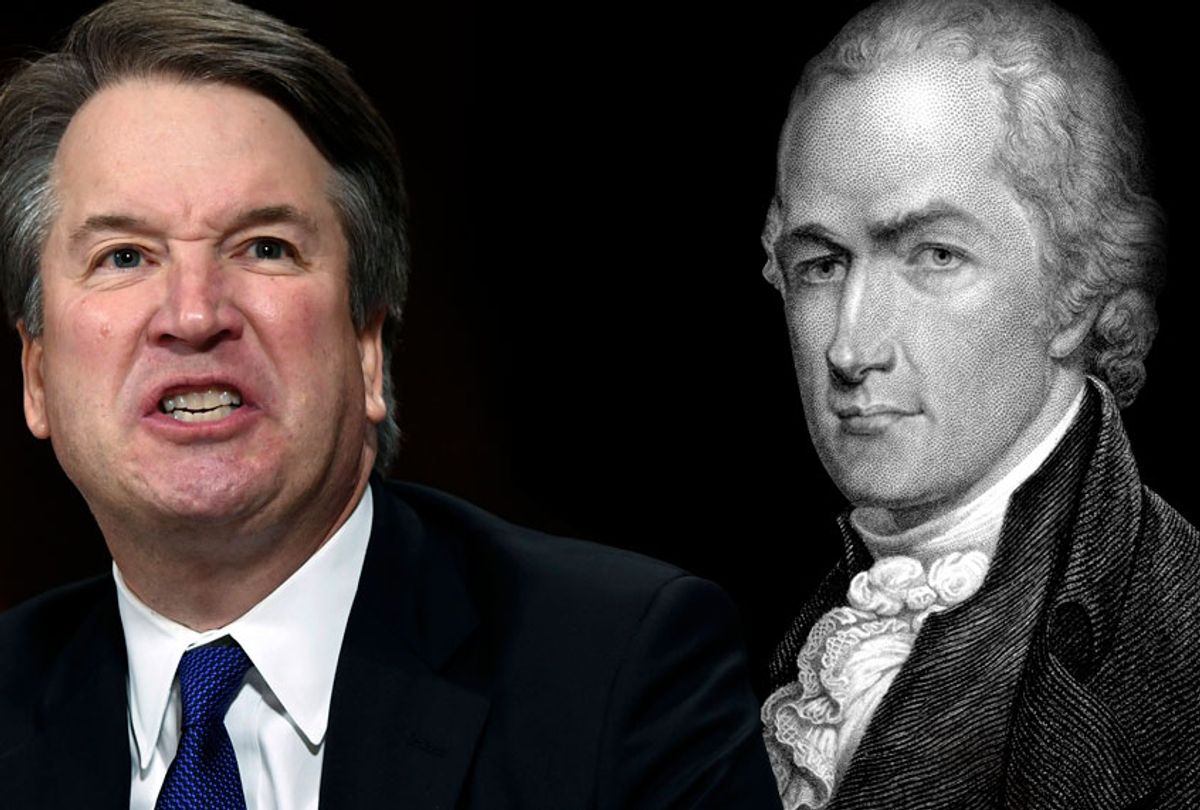

Why do we allow judges to overturn laws voted on by the people? The original reason, and still today the most persuasive rationale, for allowing federal judges to invalidate laws was stated succinctly by Alexander Hamilton in the most important Federalist Paper discussing judicial review, No. 78:

The courts were designed to be an intermediate body between the people and the legislature, in order, among other things, to keep the latter within the limits assigned to their authority. The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning, as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to be an irreconcilable variance between the two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought, of course, to be preferred; or, in other words, the Constitution ought to be preferred to the statute, the intention of the people to the intention of their agents.

In a representative democracy, governed by a written constitution, it makes perfect sense for an independent judiciary to enforce that document’s written limitations when they are violated by the other branches of government. But notice the limitation on this power articulated by Hamilton; before judges should overturn legislation there must be an “irreconcilable variance” between the law and the Constitution. Another way that some people at the time thought of this standard was that judges should act with humility and modesty when reviewing legislative acts, and only invalidate them in cases of “clear error.”

What the founding fathers did not anticipate was that the Supreme Court would over time assume the authority to use vague constitutional limitations, which in most situations are more accurately called aspirations, to legislate morality for the American people. Where the Constitution places a clear limit on our structure of government, such as that the president must be 35 years old, or that all impeachments must begin in the House and be tried in the Senate, it makes sense to speak of “irreconcilable variances.” And where the history behind a vague text is clear, such as the First Amendment’s obvious prohibition on prior restraints, it might make sense to allow the court to strike down what Jed Rubenfeld has called “paradigm” constitutional violations. But conceding all that is worlds away from allowing the Supreme Court to use imprecise constitutional text and contested historical accounts of that text to resolve many of our country’s most difficult and controversial issues of social, economic, educational and political policy.

From 1903 to 1936, the court took it upon itself to limit progressive calls for state and federal laws to regulate workplace safety, minimum wages, overtime rules and a myriad of other statutes dealing with workers’ rights. The justices struck down hundreds of statutes dealing with these issues despite no clear text or history supporting that laissez-faire ideology. All that overreaching led to a liberal backlash and the court’s retreat from the economic arena but not before many laws were overturned due to political differences, rather than violations of text or history.

The court mostly stayed out of politics between 1936 and the early 1960s except for ending formal legal segregation in public schools (substantial de facto segregation of course exists to this very day). But starting around 1963, the liberal and aggressive Warren and early Burger courts issued a series of social and moral decisions redefining how much of the country governed itself, culminating, of course, with Roe v. Wade in 1973. As my new book, “Originalism as Faith,” points out, the justices didn’t even try in many of these cases to support their opinions through constitutional text or history. Many of these decisions, such as Griswold v. Connecticut, which overturned a state law banning contraception devices, were less than 10 pages long and read more like edicts than judicial opinions.

There was a predictable backlash to the court’s many liberal opinions and once conservatives seized the court, they too started overturning laws without any showing of an “irreconcilable variance” between the laws they were striking down and the Constitution. The court has inserted itself over the last 50 years in our country’s politics by invalidating laws dealing with affirmative action, gay rights, difficult free speech questions impossible to resolve on the basis of text or history, voting rights, districting maps (one person, one vote), congressional power to enforce the 14th Amendment and numerous other disputes that in most countries would be voted on by the people, not left to the political preferences of life-tenured judges. Where the Constitution is not clear, and history contested, the justices have no legal basis to choose one outcome over the over other than their own collective ideologies.

All this explains why the confirmation process for Supreme Court justices has become so political and heated. They are not judges resolving legal disputes but a political veto council exercising authority over all 50 states and the federal government. Conservatives are happy with the court today, but there will come a time when either liberals will be in charge again or the political backlash to the court’s decisions will severely hurt the Republican Party, as the backlash to Roe has damaged Democrats. Either way, these political swings hurt democracy and our ability to govern ourselves.

We need a bipartisan effort to restructure the Supreme Court of the United States to weaken it for all time. Term limits would help, but are not nearly enough. Structural reform to make it harder for the court to overturn laws is essential, whether it takes the form of a supermajority voting requirement or jurisdiction-stripping, meaning limiting the court’s influence in areas where text and history cannot resolve hard constitutional questions.

I proposed these limitations years before the court turned sharply to the right but it is even more important today, not because of that turn but because an overly ideological court, in either direction, not only distorts our politics for the worse but allows unelected, life-tenured judges to dictate policy even when no reasonable person could argue there is an “irreconcilable variance” between the decisions made by elected officials and our written Constitution. Giving that authority to judges, liberal, conservative or moderate, is not only inconsistent with the original plan of those who first governed our country, it is a terrible idea -- as we learn every time our polity must endure yet another confirmation process nightmare.

Shares