Evil days.

The midterms were bearing down on us like a runaway train with Donald Trump in the driver’s seat and the throttle wide open, the Presidential Special hell-bent for the bottom. “Go Trump Go!” tweeted David Duke, former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, as if the president needed anyone’s encouragement. There had been no slacking after pipe bombs were sent to a number of his critics; nor after two black people were killed in Kentucky by a white man who, minutes before, had tried to enter a predominantly black church; nor after 11 worshippers in Pittsburgh were murdered at the Tree of Life Congregation synagogue by a man who’d expressed special loathing for HIAS, a Jewish refugee resettlement and advocacy organization. “HIAS likes to bring invaders in that kill our people,” Robert Bowers posted on his Gab account hours before the massacre. “I can’t sit by and watch my people get slaughtered. Screw your optics, I’m going in.”

Trump, relentless Trump, went right on raging about “invasions,” left-wing “mobs,” globalists, MS-13, and “caravan after caravan [of] illegal immigrants” invited in by Democrats to murder Americans, vote illegally, and mooch off our health care system. “Hate speech leads to hate crimes,” Rabbi Jeffrey Myers told the president in Pittsburgh several days after the murders. The FBI had previously reported a large spike in hate crimes over the previous two years, and the Anti-Defamation League noted a 60% rise in anti-Semitic incidents from 2016 to 2017. Then there was this, reported in the New York Times on the day before the election: “Advisers to the president said his foes take his campaign rally language too literally; as outrageous as it might seem, it is more entertainment, intended to generate a crowd reaction.” And Trump himself, when asked why he wasn’t campaigning on the strong economy, responded: “Sometimes it’s not as exciting to talk about the economy.”

Not as exciting as, say, hate and xenophobia. And so one was led to wonder: Do countries have souls — with all the moral consequence implied by the concept of soul? If the answer is yes, then it follows that the collective soul can be corrupted and damned just as surely as that of a flesh-and-blood human being. In this election, as in all others, grave matters of policy were at stake, but we sensed something even bigger on the line in 2018 — nothing less than whether the country was past redeeming.

Lower, smaller, meaner

“I’m on the ballot,” Trump declared at a rally in Mississippi, and so he was. For the first time in two years, the country would render its verdict on the garish aggressions of his politics, though it bore noting that many members of his party had already voted with their feet. In the preceding months, more than 40 House Republicans had resigned outright or announced that they would not seek reelection, among them the relatively moderate chairs of the Foreign Affairs Committee and the Appropriations Committee, and, most significantly, House Speaker Paul Ryan. It was an extraordinary exodus by any measure, especially for a party holding both chambers of Congress and the White House -- a party possessed, that is, of the kind of power that pols dream of. Yet here were Republicans bailing out in droves.

The usual reasons were given: the desire to spend more time with family, to confront new challenges, and so forth, but the party’s scorched-earth politics of the past 30 years, the ones that had put Donald Trump in the White House, undoubtedly had something to do with it. The hyper-partisanship championed by Newt Gingrich when he was speaker of the House in the mid-1990s, the embrace of fringe elements like the birther crowd and the alt-right, the systematic trashing of longstanding institutions and traditions (like the weaponizing of the filibuster, to name just one) and now the ultimate scorched-earther in the White House: it’s easy to imagine how the more self-aware members of the Republican caucus could see no viable future for themselves in politics.

Ryan, in particular, furnished food for thought. Like John Boehner before him, he couldn’t tame the far-right beast that was the Freedom Caucus and he had Trump to deal with too. How many nights had the Speaker tossed and turned in his bed secretly pining for rational Obama? And then there was the massive contradiction of Ryan’s own politics. Eager for Republicans to get credit for the economic expansion that began in June 2009 and was now in its 100th month, Ryan studiously ignored the fact that — predicting rampant inflation and worse — he’d opposed Obama’s program of fiscal stimulus and easy monetary policy that had produced the longest expansion in the country’s history. But Ryan’s contradiction cut even deeper. As House Speaker, at the very pinnacle of his career as a supply-side disciple and deficit hawk, he had shepherded into law a legislative agenda that was projected to start producing trillion-dollar-a-year deficits by 2020.

Paul Ryan had played out his political string. To proceed further could only monsterize his psyche, twist it into a Jekyll-and-Hyde-style schizophrenia, a form of madness not unknown among twenty-first-century American politicians. With Trump as their leader, Republicans had no place to go but lower, smaller, meaner — and so they went.

Trump praised and reenacted a Montana congressman’s criminal assault on a reporter, and suggested that U.S. troops open fire on any aspiring immigrant so bold as to throw a rock at them. In Georgia, robocalls described Stacey Abrams, a black woman and the Democratic nominee for governor, as a “poor man’s Aunt Jemima.” Congressman Duncan Hunter put out an ad characterizing his opponent, Ammar Campa-Najjar, as a terrorist sympathizer. Ron DeSantis urged Florida voters not to “monkey this up” by electing Andrew Gillum, a black man, as their governor, while in Kansas, a Republican official called congressional candidate Sharice Davids (a Native American and graduate of Cornell Law School) a “radical socialist kickboxing lesbian” who should be “sent back packing to the reservation.”

Antonio Delgado, who is black, a Rhodes scholar, and a Harvard Law School graduate, was repeatedly characterized as “a big-city rapper” in ads supporting his opponent for a congressional seat in New York’s Hudson Valley. Representative Kevin McCarthy, jockeying to replace Paul Ryan as leader of the House Republicans, loudly revived the push to fund Trump’s border wall, and Representative Steve King fantasized at a rally that Supreme Court Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor “will elope to Cuba.” Pro-GOP flyers featuring anti-Semitic caricatures were distributed in opposition to Jewish Democratic candidates in Alaska, California, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Washington, and elsewhere.

The loudest hysterics were reserved for the bedraggled, footsore “caravan of invaders” inching its way north through Mexico, several thousand desperate souls bringing, according to Trump, crime and terrorists. On Fox Business, Chris Farrell, a conservative activist, promoted the ongoing right-wing allegation that George Soros, who is Jewish, was paying migrants to come to the U.S. Kris Kobach, GOP candidate for governor of Kansas, declared that Democrats had “open-border psychosis.” Ted Cruz, fighting for his political life in Texas, led chants of “Build that wall!” at his rallies.

The final TV ad for Scott Wagner, the GOP nominee for governor of Pennsylvania, asserted that “a dangerous caravan of illegals careens to the border”; this same Scott Wagner had previously urged his Democratic opponent to wear a catcher’s mask because “I’m going to stomp all over your face with golf spikes.” Trump deployed some 5,600 active-duty troops south “to secure the border,” at a cost projected to be as high as $200 million, and his final campaign ad -- deemed so blatantly racist that Facebook and major TV networks, including Fox, refused to air it -- featured scary music, images of brown-skinned people, and a cop-killing undocumented immigrant with no known link to the caravan. The ad’s final image urged: “Stop the Caravan. Vote Republican.”

It was crude. It was dumb. It was all basically nuts. The question was: how much of America would buy it?

Record numbers

The day after the election, Trump appeared before the media to proclaim “very close to a complete victory.” Then he proceeded to riff on the size of his crowds.

It would take days — a week and then some — to measure properly the scale of the electorate’s repudiation of Trump. Despite surgical gerrymandering and voter-suppression measures that strongly favored the GOP, Democrats took control of the House by flipping 43 seats, for a net gain of 40. It was the biggest Democratic gain since the Watergate midterm of 1974, when Democrats picked up 49 seats, and the Democrats’ 9.4 million lead (and counting) in raw votes this year was the largest margin ever by a party in a midterm.

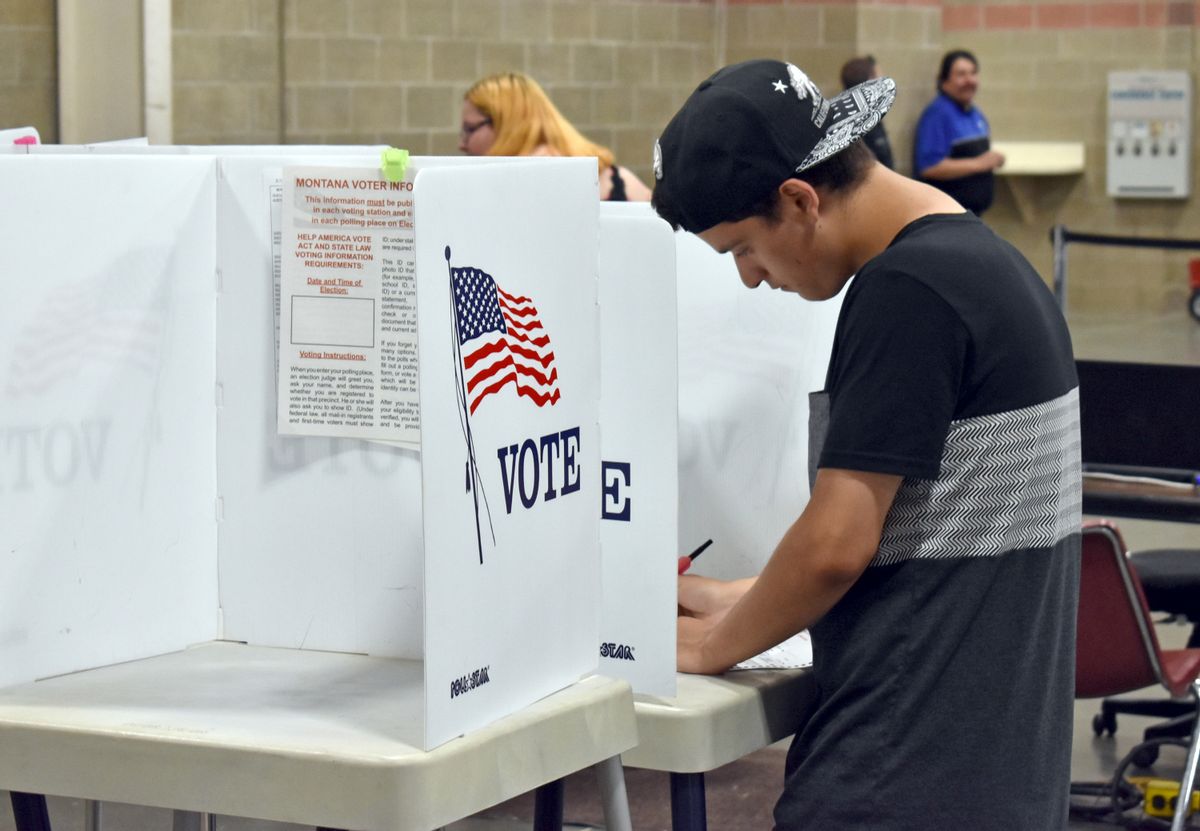

Overall turnout was the highest in 50 years: 116 million, or 49.4% of the voting-eligible population, compared to 83 million in 2014. Democrats won women -- who are not only the majority of voters but the most reliable of them -- by 19 percentage points. Particularly in the suburbs, where 50% of voters now live, white women with college degrees broke hard for Democrats, but House Democratic candidates also increased their national vote margin among white working-class women by 13 points.

Young voters and minorities (think: the future) turned out in unprecedented numbers and voted overwhelmingly Democratic. The Democrats also won independents by 12%, and voters who had opted for a third-party candidate in 2016 by 13%. Trump’s misogyny, racism, and xenophobia helped elect a new House majority that will be nearly half women, a third people of color, and include more Muslim Americans, Native Americans, and LGBTQ members than ever before.

Republicans increased their razor-thin majority in the Senate by two, but even there evidence of the Trump repudiation was strong. Democrats were defending 26 of the 35 seats in play and, in almost every race, the Democratic candidate outperformed the state’s partisan lean (the average difference between how a state votes and how the overall country votes) while racking up a nationwide total of 50.5 million votes, to the GOP’s 34.5 million.

Yeah, Beto lost. He also came within 2.6 points of knocking off a well-financed, highly disciplined incumbent in a deep-red state and was instrumental in making Texas newly competitive at both the statewide and local levels. In governors’ races, Democrats flipped seven states to the Republicans’ one and achieved a net gain of more than 300 legislative seats.

State ballot measures on politically charged issues also trended blue. Arkansas and Missouri voted to raise their minimum wage. Utah, Nebraska, and Idaho voted to expand Medicaid and, with the election of a Democratic governor, Maine will follow through on last year’s winning referendum to expand Medicaid. Florida voters approved a referendum to restore voting rights to former felons. Arizona defeated a Koch brothers-backed measure to privatize public education by a two to one margin.

Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania — states crucial to Trump’s Electoral College success in 2016 — swung dramatically back toward the Democrats in 2018.

Putting real issues front and center

This thing Trump was selling, this white-nationalist-freak-out-throwback special, played well enough to the base to flip Senate seats in North Dakota, Indiana, and Missouri, all states Trump won by big margins in 2016, as well as Florida’s closely contested Senate seat. But here’s the real shocker, the development that made this midterm “transformational,” as reported by Stanley Greenberg in the New York Times, based on a Democracy Corps election night survey: the Democrats’ biggest gains in 2018 came in rural America. Greenberg also relied on an Edison exit poll for CNN that showed the Republican margin in rural areas shrinking by double digits and a Catalist poll indicating a seven-point shrinkage.

“Exciting” the base seems to have come at a cost: a 13-point swing by white working-class women, a 14-point swing by white working-class men, and a 7-point swing among all men. While Trump’s Twitter account was acting like the social media equivalent of a spastic colon, Democrats were pushing a decidedly non-hysterical message focused on health care (coverage for preexisting conditions, preserving Obamacare, and protecting Medicare and Medicaid) and basic economic fairness. As for Trump’s manifest unfitness for office, smart Democrats assumed the president himself would pound home that message.

Yes, there was a blue wave in 2018, and the “centrist” establishment Democrats who have steered the party for the past 30 years are trying to claim it for themselves. Don’t believe them. These establishment centrists — the ideological heirs of the defunct Democratic Leadership Council who now ply their trade at the Third Way think tank in the capital, along with the big-donor class, the top-dollar Washington consultants, and the data mills that comprise the Democratic election industrial complex — stand for something far different than the blue-wave centrists who powered the party in 2018.

For more than 30 years — ever since the rise of the “New Democrats” and the Democratic Leadership Council in the 1980s — establishment centrists have practiced the top-down politics of neoliberalism, a politics founded on the free-market gospel: deregulation of banking and finance, friendliness toward corporate monopolies, limited support (at best) for labor unions and workers, the endless “liberalization” of global trade, and reflexive antagonism for the social safety net. As all the numbers show, corporate America and the One Percent reaped the lion’s share of neoliberalism’s benefits, while the Democratic Party’s once-traditional constituencies — poor people, and the working and middle classes — fell further and further behind. The party itself — once the dominant force in national politics, and in the majority of states — gradually slid into minority status, culminating in the wipeout of 2016.

2018’s blue-wave centrists are made of different stuff. This year's energy came from the bottom up, thanks to widespread local activism and grassroots organizing, much of it led by women newly politicized in the wake of 2016. The party’s small-donor base became increasingly powerful, enabling candidates like Beto O’Rourke to run robustly financed campaigns while refusing PAC money and the strings that come with it.

This same small-donor and activist groundswell made Democrats competitive in regions long ago written off by establishment centrists who have long been less focused on the concerns of working people than on cherry-picking just enough Electoral College votes to win the presidency every four years. In 2018, however, we saw Democratic candidates running and winning in deep-red areas while talking up labor unions (Conor Lamb in Pennsylvania), slamming the “rigged system” that neoliberalism produced (Max Rose on New York’s Staten Island), and pushing for common-sense gun control (Lucy McBath in Georgia).

Democrats interested in taking back the Midwest should look to the example of Ohio’s Sherrod Brown, one of Bernie Sanders’s closest allies in the Senate. A strong voice for labor and the middle class and a longtime skeptic of international trade deals, Brown won reelection by seven percentage points in a state otherwise trending Republican. The same was true for Senator Amy Klobuchar, who has prioritized the interests of working people her entire career. She won reelection by 24 points in Minnesota, a state Trump almost won in 2016.

The blue-wave centrists put real issues front and center: housing, wages, access to health care, basic fairness and opportunity for working people. Whatever name you want to put to these issues — centrist, progressive, populist, lunch bucket, kitchen table — these haven’t been the priorities of the establishment centrists of the past 30 years. For a clue, look no farther than the Third Way’s close ties to K Street, the epicenter of corporate lobbying in Washington, and to the investment banking industry.

Trump lost in 2018, but he remains nearly as powerful as ever. He’s a sitting president with a ferociously loyal base, a Senate majority that’s about to get bigger, and a federal judiciary that hews further to the right with each new raft of appointments. In the days since the election he’s shown no moderating tendencies, instead threatening the incoming House Democratic majority with a “warlike posture,” firing Attorney General Jeff Sessions, illegally“appointing” a sketchy acting attorney general, further defying the Refugee Act of 1980, banning a CNN reporter from the White House, and defending Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in the state-sponsored murder of dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Trump is still Trump, and America is still America. In the days after the election, wildfires raged through northern California, leaving scores dead and many thousands homeless, and in the country’s 307th mass shooting in the first 313 days of 2018, a gunman killed 13 people at the Borderline Bar & Grill in Thousand Oaks, California.

Welcome to the struggle for the country’s soul. We haven’t seen anything yet.

Ben Fountain’s Beautiful Country Burn Again: Democracy, Rebellion, and Revolution has just been published by Ecco/HarperCollins. He is the author of a novel, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, which received the National Book Critics’ Circle Award and was a finalist for the National Book Award, and a story collection, Brief Encounters with Che Guevara, which received the PEN/Hemingway Award and the Barnes & Noble Discover Prize for Fiction. He lives in Dallas.

Shares