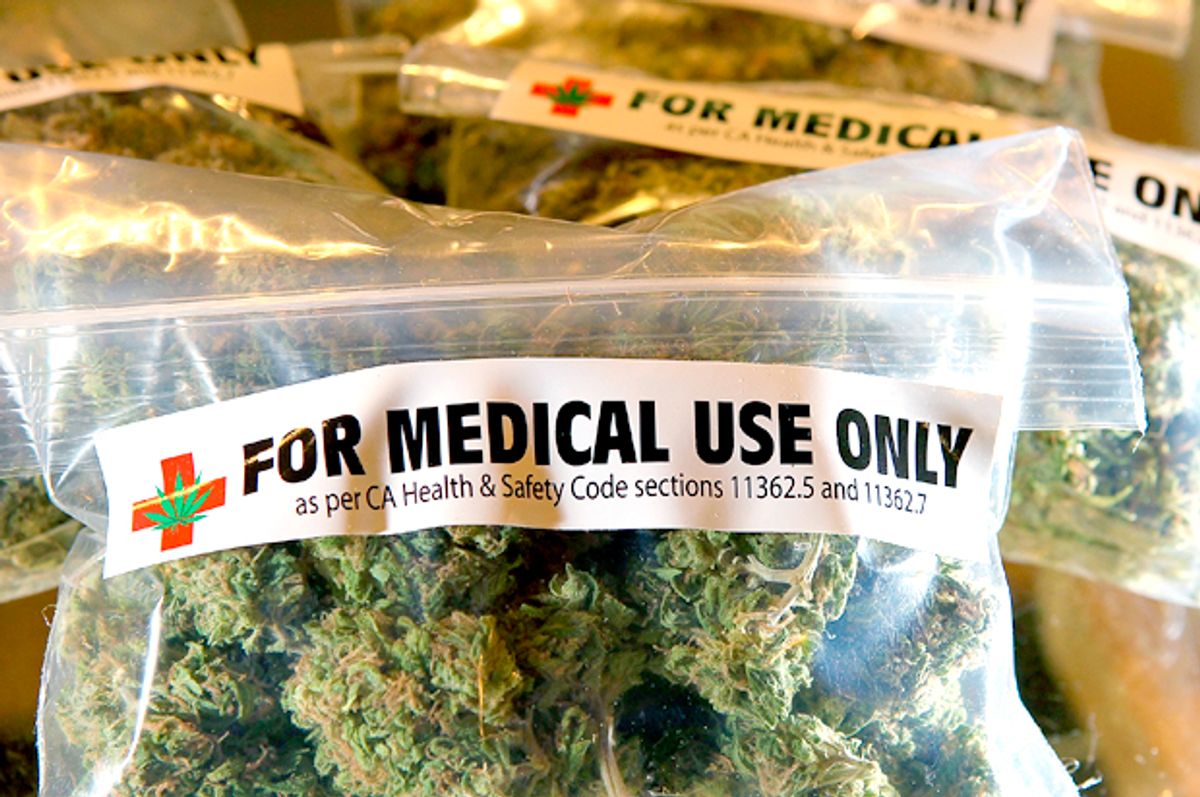

Republican state legislators in Utah replaced a medical marijuana initiative that voters voted into law with their own bill that has far stricter limitations on medical cannabis after lobbying from the Mormon church, the Salt Lake Tribune reported.

Voters approved Proposition 2 in November, making Utah one of 32 states to legalize medical marijuana. On the first day that the law went into effect, lawmakers in the state legislature voted along party lines to override voters and replace the law with a “compromise” that appeases the law’s opponents, including the Mormon church.

The “compromise” bill reduces the 40 medical dispensaries permitted by Prop. 2 to only seven “pharmacies.” Most of the distribution will be state-run.

While Prop 2 legalized THC-infused edibles, the compromise bill bans most edibles except for gelatin cubes. The legislation also removed most autoimmune diseases from the list of illnesses that qualified for cannabis treatment.

After the legislation was signed into law by Gov. Gary Herbert, two pro-marijuana groups that worked to pass the ballot initiative filed a lawsuit against the the state, arguing that the legislature violated the Utah constitution by overriding the will of the voters and that the Church of Latter-day Saints' involvement in the overhaul violated another part of the state’s constitution.

"Anything that defeats the right of the people to pass their own legislation under our constitution should be declared unconstitutional. Otherwise it’s totally illusory," Rocky Anderson, an attorney for the group TRUCE, told KSTU.

TRUCE, along with the Epilepsy Association of Utah, is seeking a court injunction blocking the state from enacting the legislature-passed law and forcing the state to revert back to Prop. 2.

"If there is any meaning in our Constitution as to the people’s right through direct democracy to pass initiatives and hence legislation, it’s got to mean way more than the bill is there one day and defeated by the legislature two days later," Anderson said.

Former federal judge Paul Cassell told KTSU that he believes the groups “don’t have a very good case under current law. While the voters have a right to enact a law, the legislature has the right to change it.”

But Anderson told ThinkProgress that he believes the religious freedom argument gives the groups a fighting chance.

“Because of Utah’s unique history of having had a theocracy prior to statehood, there was a unique provision in Utah’s constitution that goes beyond most states [that] prohibit the establishment by the state of any state religion,” he explained. “The Utah state constitution expressly prohibits the control of the state or interference in its functions by any church, and that’s exactly what we saw here.”

The move to gut a voter-approved initiative mirrors similar moves by Republicans in states like Florida and Michigan.

Florida voters overwhelmingly approved an amendment that automatically restores voting rights for roughly 1.5 million residents convicted of a felony, except for those convicted of murder or felony sexual offense. Now, Gov.-elect Ron DeSantis says that the amendment should not be enacted as approved by voters, and has called for state lawmakers to add “implementing language” in a bill that he would then sign.

The Tampa Bay Times reports that the move would delay the restoration of voting rights by at least two months, because the next legislative session does not begin until March. Supporters of the amendment fear that lawmakers will gut the amendment and make it more difficult for voting rights to be restored.

In Michigan, Republicans took an even more cynical approach by voting to approve a minimum wage hike and sick leave protections before the midterm elections -- in order to prevent them from being approved by voters on the November ballot -- only to gut those very laws immediately after the election.

Shares