Ground zero in the global battle against climate chaos this week is in Wet’suwet’en territory, northern British Columbia. As pipeline companies try to push their way onto unceded Indigenous territories, the conflict could become the next Standing Rock-style showdown over Indigenous rights and fossil fuel infrastructure.

Since 2010, the Unist’ot’en clan, members of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation, have been reoccupying and re-establishing themselves on their ancestral lands in opposition to as many as six proposed pipeline projects.

The Unist’ot’en camp now houses a pit-house (a traditional dug-out dwelling), a permaculture garden, a solar-powered mini-grid and a healing lodge, where community members receive holistic and land-based treatment for substance abuse. The camp also defends the sacred headwaters of the Talbits Kwah (Gosnell Creek) and Wedzin Kwah (Morice River), spawning grounds for salmon.

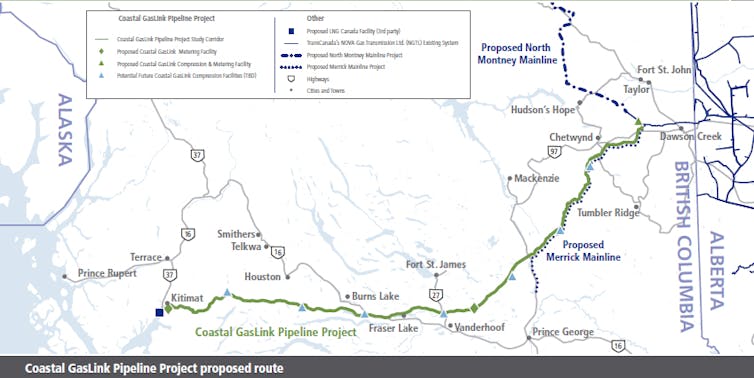

If built, the Coastal GasLink pipeline project, first proposed in 2012 and approved in October 2018, would run approximately 670 kilometres across northern B.C., bringing fracked gas from Dawson Creek to the Port of Kitimat. It is part of a recently approved $40 billion fracked-gas project, called LNG Canada, the single-largest private-sector investment in Canadian history.

B.C. Oil and Gas Commission

But the Unist’ot’en territory is in the pipeline’s path. Community members are committed to resisting pipelines through their unceded lands.

They have turned back TransCanada’s contractors by reviving their own traditions of “free, prior and informed consent,” where the community has established a protocol controlling who accesses their territory. As a result, no pipeline work has yet been done on their lands.

TransCanada, the company behind the Coastal GasLink pipeline project, recently served an injunction and civil lawsuit to the members of the Unist’ot’en camp. The injunction will be heard today (Dec. 13) in Prince Rupert, B.C. If granted, it will allow the the RCMP to arrest and remove everyone from the camp.

The threat of eviction has sparked outrage and support across Canada. As a visitor, researcher and filmmaker, I had the opportunity to visit the camp in 2012. The Unist’ot’en represent a powerful story of decolonization and transformation.

Their approach of asserting responsibility to the land and the fish rather than demanding rights from the state, land-based healing of colonial trauma and re-invigoration of Indigenous laws and protocols are an inspiration for land defenders and climate justice activists in Canada and around the world.

Bulldozing through their territory would lead to a major confrontation at a moment when the federal government has expressed a commitment to reconciliation with Indigenous communities.

Hereditary leadership

Coastal GasLink has negotiated agreements with the elected councils of all 20 First Nations on the route. But the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs, the leaders according to traditional governance and decided by consensus in the community, say they are the only authority that can legally sanction development in their territory.

The community says the Unist’ot’en camp is not a blockade, protest or demonstration. It protects against encroaching industrial developments and creates a space for the community to “heal from the violence of colonization.” TransCanada’s attempt to enter their territory by force is an extension of this colonial violence, the community says.

The Wet’sewet’en and the adjacent Gitxsan First Nations were plaintiffs in the ground-breaking Delgamuukw court case, heard by the Supreme Court of Canada in 1997. The ruling recognized that the Wet’suwet’en rights and title to 22,000 square kilometres of northern B.C. had never been extinguished.

Despite this, federal and provincial governments continue to push through industrial and extractive projects without consent

Informed consent

In the lead-up to the 2015 federal election, Justin Trudeau promised a new nation-to-nation relationship and said his government would “fully adopt and work to implement” the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

UNDRIP includes the provision that “Indigenous peoples have the right to determine and develop priorities and strategies for the development or use of their lands or territories and other resources.” However, the Trudeau government has abandoned its commitment to informed consent, and requires only “duty to consult and accommodate.”

The government’s failure to respect internationally recognized Indigenous rights while pushing through projects such as Kinder Morgan is widely considered a betrayal by Indigenous communities in Canada.

TransCanada’s attempt to evict the camp must also be seen in a global context of increased threats against Indigenous communities. According to Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples:

“The rapid expansion of development projects on Indigenous lands without their consent is driving a global crisis. These attacks — whether physical or legal — are an attempt to silence Indigenous Peoples voicing their opposition to projects that threaten their livelihoods and cultures.”

The stakes here are high. If the Canadian government evicts the camp with a violent incursion into unceded territory it does so at its own peril. It could become a showdown like the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline that centred around the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota.

The camp has become a powerful symbol against extractive projects, and for Indigenous sovereignty and decolonization in practice across Canada and beyond. Communities across Canada have already begun responding to the Unist’ot’en call for support. Protests have been held across Canada and more than 65 organizations and 2,771 individuals have said they stand with the Unist’ot’en.

Many say they will travel to the camp to defend the Unist’ot’en if need be. What’s clear from these pipeline politics is that First Nations are not backing down and have pledged to continue to resist extractive projects and colonial incursions into their territories. The Wedzin Kwah may be the next battleground for the global movement for climate and environmental justice.

Leah Temper, Research Associate, McGill University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.