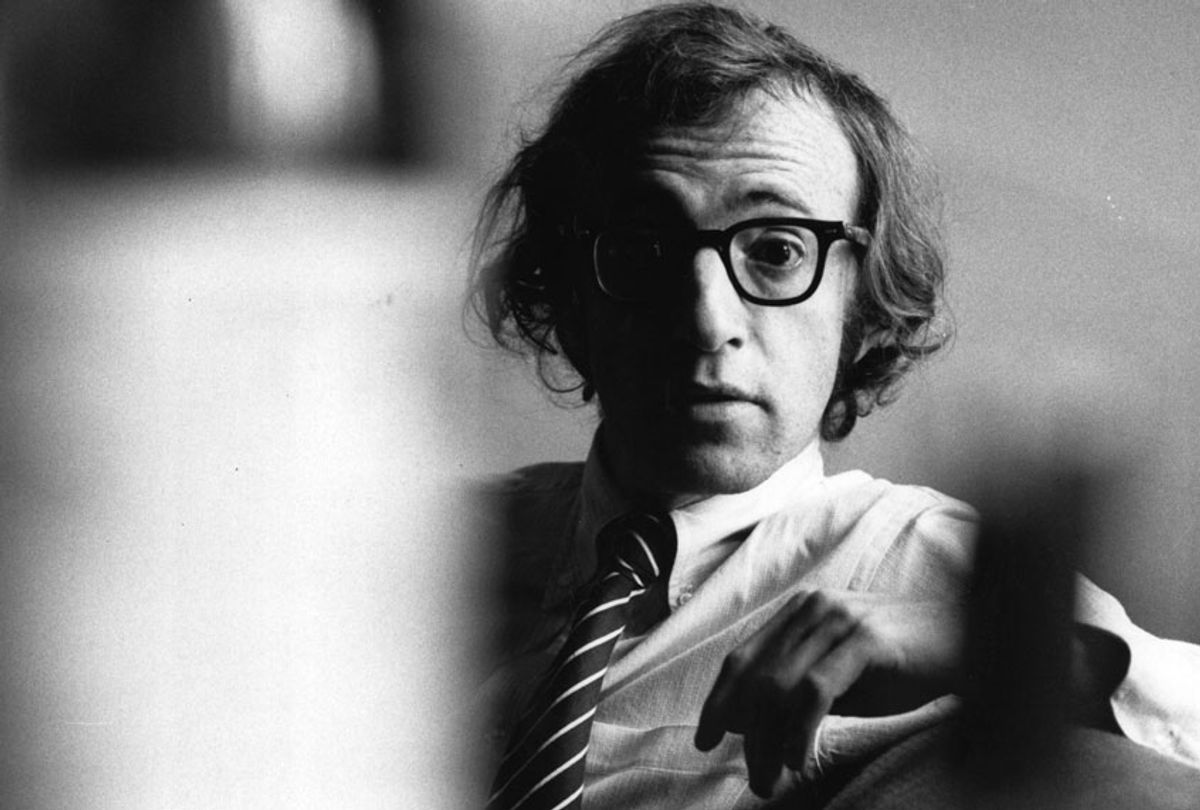

On Monday, The Hollywood Reporter published a story in which a former model named Babi Christina Engelhardt, labeled quite salaciously in the headline as “Woody Allen's Secret Teen Lover,” gave her account of an eight-year relationship she claims to have started with Allen in 1976 when she was 16 and he 41. Who among us was surprised to learn that the man who wrote a high school girlfriend for his forty-something protagonist in the film “Manhattan,” widely considered a classic work of cinematic genius before Allen’s art became non grata along with his persona, and who then pursued the young actress who played said teenage love interest pretty much the second she turned 18 (according to Mariel Hemingway herself), had allegedly been “dating” young girls on the sly for years? Anyone?

You don’t have to be gobsmacked to be dismayed, of course. Engelhart’s story is a multifaceted one, and she was bound to lose control of it almost immediately as spectators choose sides and cast her as either a helpless victim or an opportunistic ingénue, when the truth appears to exist not only in between but also outside of that dichotomy, as something else entirely we don't always have the vocabulary to discuss productively. America rarely takes teenage girls and their complex desires and vulnerabilities very seriously, so to expect a more nuanced discussion than the debate over exactly what style of monster Allen is would be to set the enterprise up for failure. And yet this is also a completely understandable state of discourse; the stories of exploitation and objectification and manipulation and abuse and violence that we’ve been immersed in collectively over the last year, and that have swirled around us for years before that about powerful men and their shameful behaviors, have a way of shaping themselves around the stories we already carry inside us, for better and for worse.

For me, THR's summary of Engelhardt as a girl "with a confident streak and a painful past" made me catch my breath:

The pair embarked on, by her account, a clandestine romance of eight years, the claustrophobic, controlling and yet dreamy dimensions of which she's still processing more than four decades later. For her, the recent re-examination of gender power dynamics initiated by the #MeToo movement (and Allen's personal scandals, including a claim of sexual abuse by his adopted daughter Dylan Farrow) has turned what had been a melancholic if still sweet memory into something much more uncomfortable. Like others among her generation — she just turned 59 on Dec. 4 — Engelhardt is resistant to attempts to have the life she led then be judged by what she considers today's newly established norms. "It's almost as if I'm now expected to trash him," she says.

Time, though, has transfigured what she's long viewed as a secret, unspoken monument to their then-still-ongoing relationship: 1979's Manhattan, in which 17-year-old Tracy (Oscar-nominated Mariel Hemingway) enthusiastically beds Allen's 42-year-old character Isaac "Ike" Davis. The film has always "reminded me why I thought he was so interesting — his wit is magnetic," Engelhardt says. "It was why I liked him and why I'm still impressed with him as an artist. How he played with characters in his movies, and how he played with me."

Allen and Mia Farrow, his partner during part of this timeline, who Engelhardt claims participated in threesomes with them, both refused to comment to THR for the story. The timing, however, does answer the major question of “why now?” around the puzzling softball profile of Allen and wife Soon-Yi Previn (Farrow’s adopted daughter, for those who are just joining us from an unaware planet) that Allen buddy Daphne Merkin wrote for New York Magazine a few months ago. Nothing like getting out ahead of a big story with a little preemptive damage control that changed exactly nobody’s opinion about Allen, and only somewhat complicated the narrative around Soon-Yi.

But given, as THR points out, "the recent re-examination of gender power dynamics initiated by the #MeToo movement," Allen's PR offensive never had a chance. Which is to be expected, but even the utter lack of surprise around Engelhardt’s revelation doesn’t let us off the hook for a conversation about what happened and why it’s still important 40 years later. This isn’t really a story about Woody Allen, as much as we might like for it to be. After all, we can wrap our heads and our hearts around an individual — even as individual after individual is revealed to be awful, and on top of that so in love with his own story that he can’t even begin to fathom that he’s not entitled to just do and take as he pleases — and that makes the reckoning we're hopefully gearing up to fully experience a little easier to control.

We talk a lot about how the power that comes with fame shapes how these events unfold and bends the institutions around those men in their favor. And it’s true that in a celebrity-obsessed culture, fame insulates the carrier from certain consequences. But fame also obfuscates and exceptionalizes; it allows us to pin a bold-faced name — one very special man at a time — to terrible behavior and its fall-out, just as we once pinned that very special man's face and name to his achievements.

And so at some point, if we're going to get beyond the limiting scope of dwelling primarily on the Brett Kavanaughs and the Louis CKs and the Woody Goddamn Allens, we have to stop talking only about famous men and start examining the stories we have told ourselves and allowed ourselves to be told that transcend celebrity, those stories we carry inside of us around which we collectively shape these famous bad-men narratives, and which in turn shape the institutions and cultural beliefs that allow these damaging behaviors to play out among the non-elite as well.

Let's start with Engelhardt's realization that "Manhattan" — once my favorite movie, which then caused me to reevaluate my parents' own 1970s "Manhattan" love story in the full clarity of adulthood — represented a particular unrealized fantasy of Allen's:

. . . Engelhardt is struck by how, to her, Allen had conjured a make-believe world in which Ike could conduct his relationship with a teenage partner, able to parade her in public and among friends in a fantasyland devoid of any disapproval, noting how it contrasted with her own enforced seclusion. "I was kept away," she observes. The ethical milieu Allen establishes among the rest of the adults in the film is striking. Without exception, they're either bemusedly ambivalent or outright supportive of the pair's relationship.

My father was 36 when he took my mother out on their first date to a seafood place in the Village. She was 15, with a confident streak and a painful past. He had a story he told himself about the world and what he was owed. She had hitchhiked across the country and lived by her wits among the street kids and freewheeling counterculture of the early '70s, and yet also was shaped by a military upbringing, in which a man's rank confers all power. At the photos from their wedding later that year, they are surrounded by adults — their best friends, both of his parents and his sister — and my mother, in her long white cotton dress embroidered with little flowers, looks like a radiant teenage girl being seen off by extended family to a school dance.

Given what I know and have learned about my mother's New York in the 1970s — which isn't limited to her New York, it was also Boston, and Los Angeles, and San Francisco, and Aspen, and, and, and — Woody Allen's outsize fame at the time is likely all that made him keep his relationship with Engelhardt a secret. The "ethical milieu" of ambivalence he dreamed of was all around him, in fact, maybe as far away as a subway ride downtown. It’s possible that Allen’s own sense of shame — hard as that may be to imagine now — was a stronger factor than the opprobrium he feared from external sources.

Was my mother — tall and poised and beautiful, too, downright luminous — exceptional? Yes, of course; and no, definitely not. In learning her stories, and the stories of other women who came of age around the same time, I've come to understand in new ways how the late'-60s and early'-70s liberating counterculture in general and the sexual revolution in particular benefited men, because they had a head start on the power. "I can’t tell you how many times, if I would say no, they’d say why are you so uptight? That was like the worst thing to be called back then," one of my mother's old friends told me recently when describing the social scene in one hipster epicenter where men old enough to have up-and-coming careers at places you've heard of were dating girls young enough to still be in high school. What box would a girl fit herself in to avoid that label? For all the handwringing about contemporary cancelation culture, we need to keep asking if those boxes really have changed significantly in the decades since. How much longer do we have to work in them, and around them, before they're smashed completely?

You can hear that sentiment too in Engelhardt's account of how she says Allen brought other girls and women into bed with them, and again her clear self-assessment of what made her attractive to powerful men in general: "I was pretty enough, I was smart enough, I was nonconfrontational, I was non-judgmental, I was discreet, and nothing shocks me."

Remove the parts about being non-judgmental and un-shockable and she could be describing the constricting ideals of "proper" femininity that were thought to have been shed like so many bullet bras and crinolines on the floor where their symbolic constriction belonged. And it's clear who the beneficiaries of all of those traits were designed to be. But what really makes me laugh in recognition is this: it sounds exactly like the cool girl ideal I grew up striving for in the '90s, and which I still see compelling us at times to contort our inner compasses around the trespasses of men we admire. I no longer wonder where we learned it. But are we still passing it down?

The conversation around Allen for those of us who don't know him personally or professionally often stops at the threshold of whether or not we can, or should, separate the artist from his product, which is to say, whether fans of "Manhattan" — as I once was — can or should still applaud his achievement, now that we see the girls behind it. But once again, I think we let ourselves off easy if we dwell on our feelings about one special man and how his personal misdeeds crash up against his singular work of art. I have come to see this while digging into the various paper trails attached to my own father, who died when I was five and left so many underaccounted, and sometimes outright dishonest, details behind. I am trying to reconstruct the man who would make such a self-serving choice, which is also a choice that resulted in me. Can I understand him without excusing him, but also without making my mother a victim, which she does not want to be? Can I love my father and not regret my own existence?

What does any of this have to do with Woody Allen? As Engelhardt finishes re-watching "Manhattan" for the story, THR reports that she "offers a final thought for the evening. What if it had been the teenage girl's story that had been the center rather than that of the middle-aged man? 'It's a remake I'd like to see.'" That's a worthy enterprise, for those who survive these men, famous and not, and those who bear witness. "Manhattan" can't be erased from the record any more than I can. It's how we frame those stories and re-tell them going forward that will matter.

Shares