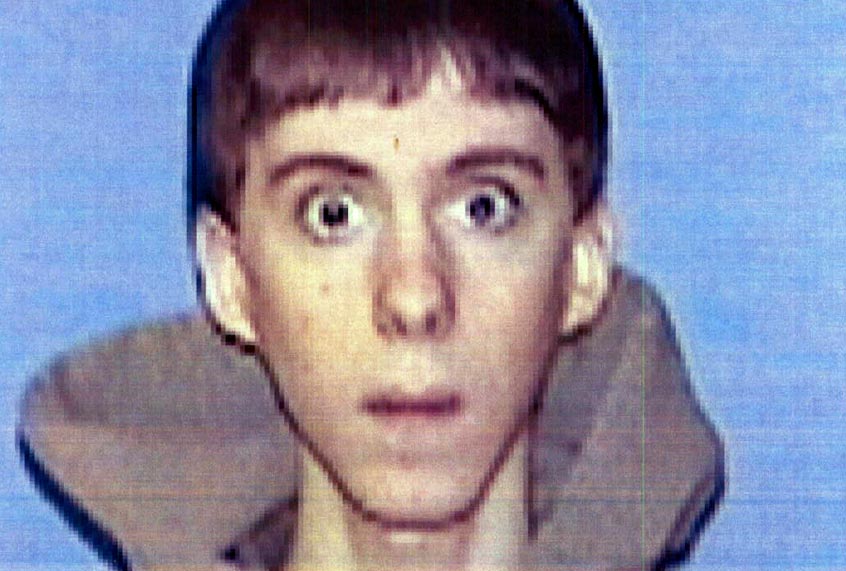

Shortly after the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, someone very close to me became upset after one of her co-workers made a comment disparaging autistic people. The shooter in that case was a young man named Adam Lanza, and while news outlets did their best not to focus on the fact that he was on the autism spectrum, those who have prejudices about individuals with this condition — with my condition — often noticed that detail.

Six years later, new light has been shed on Lanza — who killed 26 innocent people at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, after murdering his mother and before committing suicide — because the Hartford Courant acquired more than 1,000 pages of documents about him from the Connecticut State Police. There are many disturbing facts about Lanza in those documents, such as that he kept a spreadsheet about 400 mass murderers, obsessed over pedophilia and kept a lengthy list of daily grievances.

This one paragraph from the Courant’s report seemed to capture the essence of the whole:

Diagnosed as a child with a sensory disorder and delays in speech, he would exhibit a quick mind for science, computers, math, and language. The few acquaintances he had as a teenager came from video game arcades and online gaming chatrooms. The newly released writings express a wide range of emotions and rigid doctrine, from a crippling aversion to the dropped towel, food mixing on his plate and the feel of a metal door handle, to a deep disdain for relationships, an intolerance of his peers, a chilling contempt for anyone carrying a few extra pounds, and a conviction that certain aspects of living are worse than death.

The Courant also noted that Lanza’s social isolation “had its roots in his developmental speech delays as a child, the first of a string of diagnoses that included Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Sensory Integration Deficit, and Autism Spectrum Disorder.” It also quoted Yale psychiatrist Robert King’s observation after interviewing Lanza that he had “the rigidity of a youngster with autistic spectrum disorder.”

When I spoke with a medical expert about the stigmas associated with being on the autism spectrum, she didn’t hold back.

“We hold people with brain disorders to a different standard than we do for people with other medical conditions,” Dr. Audrey Brumback, a pediatric neurologist and professor at Dell Medical School at the University of Texas in Austin, told Salon by email. “People often wonder why a person with depression, anxiety or autism can’t just use ‘mind over matter’ to change their thinking and behavior. By contrast, nobody would ever say that to a person with diabetes because we intuitively know we can’t use mind over matter to get the pancreas to start working properly. In order to understand people with brain disorders, we need to understand that they have medical conditions. These ‘mental health’ disorders are medical disorders of the brain, just like some forms of diabetes are medical disorders of the pancreas.”

She also offered a simple way to explain autism to people who may be unfamiliar with it.

“We all process information differently. People with autism process information in a fundamentally different way than people without autism,” Brumback explained. “Many of the behaviors a person with autism has stems from this difference in how their brain processes information.”

I also reached out to Alex Plank, the founder of WrongPlanet.net, and a writer and actor with autism.

“As someone on the spectrum, I’ve experienced a wide variety of reactions to autism,” Plank told Salon by email. “Over the years, the general perception has shifted to be more positive and accepting. I’ve felt much better about the perception so it’s important that we make sure this continues. The way to further improve our perception is to show more positive and realistic examples of autistic people in the media. We make up a large portion of the population yet our representation in the media — in narrative TV and film — is disproportionately lower than it should be.”

Plank also described how, like me, he had encountered negative stereotypes about autism and was concerned about the discussion of Lanza’s autism after the Sandy Hook shooting.

“In general, I’ve definitely heard negative stereotypes get thrown around. I’ve even seen the word autism or autistic used as an insult,” Plank explained. “I wrote an op-ed for CNN after Sandy Hook about how damaging it was to even bring up autism in the discussion surrounding this event. Autism has nothing to do with violence and it certainly isn’t relevant to the news coverage of a mass shooting. If autistic people were more understood, I think these problematic representations would become much more uncommon.”

Both Brumback and Plank said that they feel societal attitudes toward autism are improving.

“It was only a few decades ago that we blamed a child’s autism on poor parenting skills,” Brumback told Salon. “Thankfully, we now understand that autism is a biological disorder that begins early in development, and that in fact autism is largely a genetic disorder. It stems from differences in how the brain develops. As research helps us understand more about the biology of autism and related disorders, our society will become even more accepting of people who have differences in how their brains work.”

Plank made a similar point, focusing specifically on how “there’s an effort in the media to be more inclusive of those who are different.” “Hopefully we will see more stories being told by autistic people, more openly autistic actors and television personalities, more characters in shows, and even more athletes talking about being on the spectrum,” he continued. “I think media has a power to change the perception of the public and the responsibility to use that power to do so.”

While I agree with Brumback and Plank, I personally think it is valuable to look at the full scope of Lanza’s dark mental world to improve our understanding of autism. It is clear that being autistic was only one aspect of who Lanza was, and just as obvious that the part of him that decided to commit mass murder had nothing to do with that aspect of his brain. Autistic people are like anyone else in the sense that their actions can be good, evil or neutral. Most autistic people, like most people in general, fall somewhere on the good-to-neutral spectrum. But as with the human population in general, every so often you get an Adam Lanza who chooses (or who cannot resist) the path of evil.