Christmas in 1968 was the first I would spend apart from my family. I was a cadet at West Point, and my parents and sisters lived in Hawaii, and I couldn’t afford to fly there for the holidays, so I called a woman I had been seeing in the city and asked if I could stay with her. To my great relief, she said yes.

She was a nurse who worked nights and lived on a bombed-out block of East 2nd Street, between Avenues A and B, as I recall. I took the bus to Port Authority, grabbed the shuttle to Grand Central and took the Lex to Bleecker Street and walked east. It was around freezing, and a stiff wind was blowing. The further east I walked, the more deserted the streets were. Her block faced husks of deserted buildings and empty lots with Houston Street just beyond. It felt like a landscape out of some kind of post-apocalypse movie — boarded-up doors and blown-out windows, a few cars up on cinder blocks with missing wheels and tires, empty lots piled with derelict mattresses and broken furniture and plain old garbage. Even in the bitter cold, the street stank.

But not as much as the entryway of her building. I smelled it the minute I pushed open the door: that sickly, sweet, somehow thick odor of death. It mixed with the smells of frying grease and garlic and peppers and onions and got stronger as I went up the stairs. I turned onto the third floor and knew there was a body behind one of the doors. Her place was on the fourth floor, and when she opened the door, I asked her, don’t you smell that? I know, she said. The Puerto Ricans are always cooking stuff in this building.

I threw open a window to flush the smell out of the apartment and looked up the number for the Fifth Precinct and called them. A couple of beat cops showed up an hour or so later, and after them came a truck from the morgue. They hauled out the body of an old man who had died alone in his apartment a few days previously. After they left, I went downstairs and propped open the front doors, and over the next day or so, the smell of death was gradually overtaken by the odors of fried food and cheap wine that had been spilled by winos trying to escape the cold. It was four days until Christmas.

She was a few years older than me, and we didn’t have a relationship as much as an arrangement. In the afternoons, we would lie around on her narrow bed in the front room watching a black and white TV until she had to put on her uniform for work, then we would venture out into the cold and dark New York winter and meet up again when she came back sometime after midnight. I’d usually pick up something from one of the bodegas on First or Second Avenue, and we’d eat a late dinner in her kitchen and drink some wine and go back to bed.

The temperature dropped into the 20s on the day before Christmas, and with the wind blowing through the cracks around the old tenement windows, the radiators in her place struggled to keep up. We huddled under a pile of blankets and quilts until she had to go to work. She had a later shift that night, so it was 9:00 by the time we bundled up and hit the street. I walked her over to the bus she took up First Avenue to Bellevue Hospital. I had read in the Voice that there would be a Christmas eve poetry reading at St. Marks in the Bowery, so I headed up Second Avenue.

Inside the church, it was a real old-fashioned beatnik scene. The place was crowded with long-haired East Village characters wearing long woolen overcoats and their old ladies in raccoon coats they’d picked up in the second hand shops on St. Marks Place. Someone was passing out cups of red wine at the door, and everyone was in a festive mood.

Up on the altar at the front of the room were several real beatniks: Hubert Huncke, known as “Huncke the junkie,” who was famous for his ability to scrounge up the scratch to feed his habit while staying out of jail; Gregory Corso, a diminutive pinch-faced guy with a cloud of curly hair and a mischievous smile; Ed Sanders, famous as an “investigative poet” and one of the Fugs, who ran the Peace Eye Bookstore, where he published “Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts.”

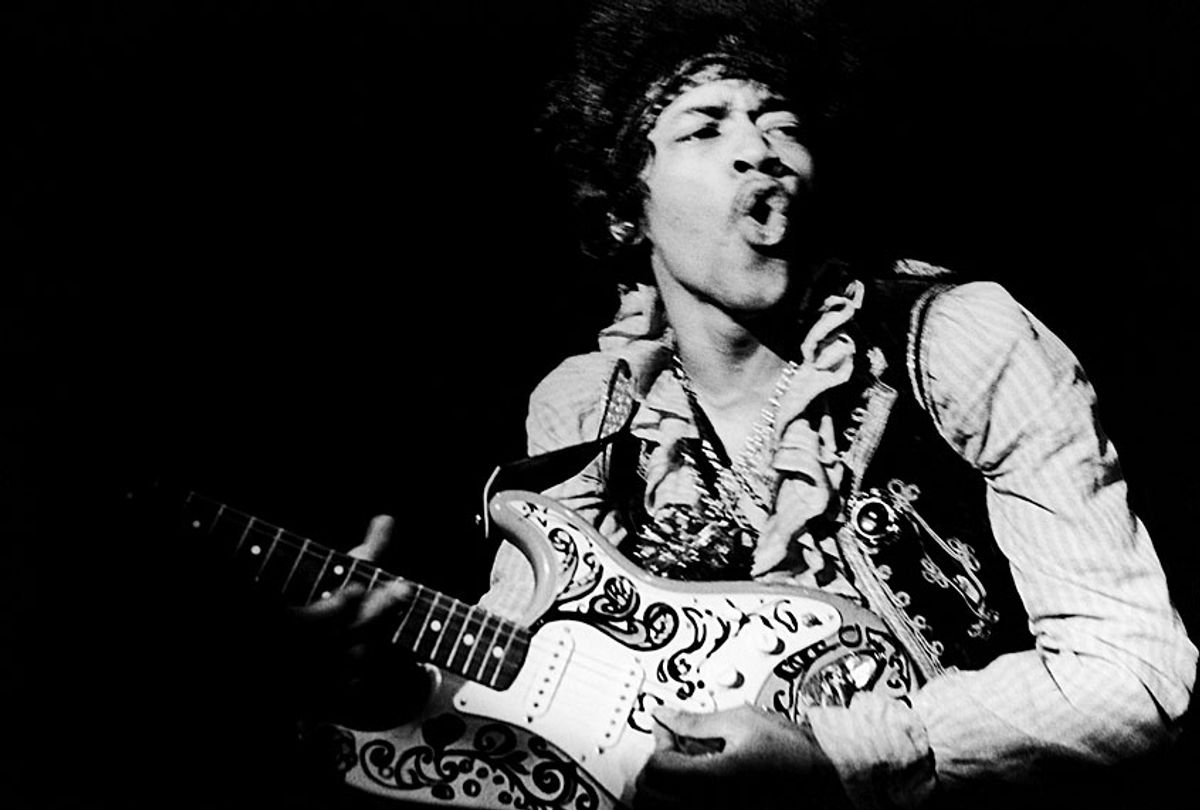

I took a seat on one of the pews several rows back from the front. They began playing a tape Allen Ginsberg had sent from somewhere upstate for the occasion, reading his poetry in his distinctive cadences, cheerful no matter the subject matter. Ginsberg’s chant was filling the church when I smelled a woosh of patchouli oil to my right. I turned just as Jimi Hendrix slid in and sat down next to me. He was wearing a black hat with a wide brim and a fancy hat-band and a furry fringed vest and feather boas and a big silver belt that rode low on the hips of his bellbottoms. With him was an entourage of gorgeous young women chattering excitedly. Jimi sshhhed them.

We sat there for the next hour listening as East Village poets cried out in political protest and in celebration of sex and pot and Buddhism and the vegetarian lifestyle. Gregory Corso read a poem that managed to be angry and funny at once, and Ron Padgett read, and from Warhol’s factory Gerard Malanga read, and then there was an intermission. Hendrix and his crew stood up and left, and I thought they were gone for good, but they came back and sat where they had been before, and Jimi shhhhed his entourage again when Ed Sanders took the mic and read a bawdy poem about a motel room. Then Ed read a poem he had published in the Voice earlier that year when one of the Voice’s best writers, Don McNeill, had died unexpectedly. It was a sad, beautiful poem that captured something about that year, 1968, in its celebration of the death of a man who had covered the descent of hippiedom from pot and rock and roll and be ins into speed and smack and murders on Avenue B.

Ed finished reading, and everyone sat silently for a moment, and then it was over. Hendrix stood, and in a rush of boas and fringe and patchouli, he was gone. He had sat there listening to poetry for at least two hours, and he never said a word. After that night, I never listened to his music the same way again because I heard in his lyrics the rhythms of that night, his beat allusions to “happiness staggering down the street footprints dressed in red,” while “the wind whispers Mary.” I mean, how could you not hear his debt to the Beats amongst his brilliant guitar licks?

Hendrix was a poet who went out on a frigid New York Christmas eve to listen to poetry. He would be dead in London a year and a half later, but on that night in 1968, at the end of a year of protests and turmoil and war and assassinations, he was happy.

Shares