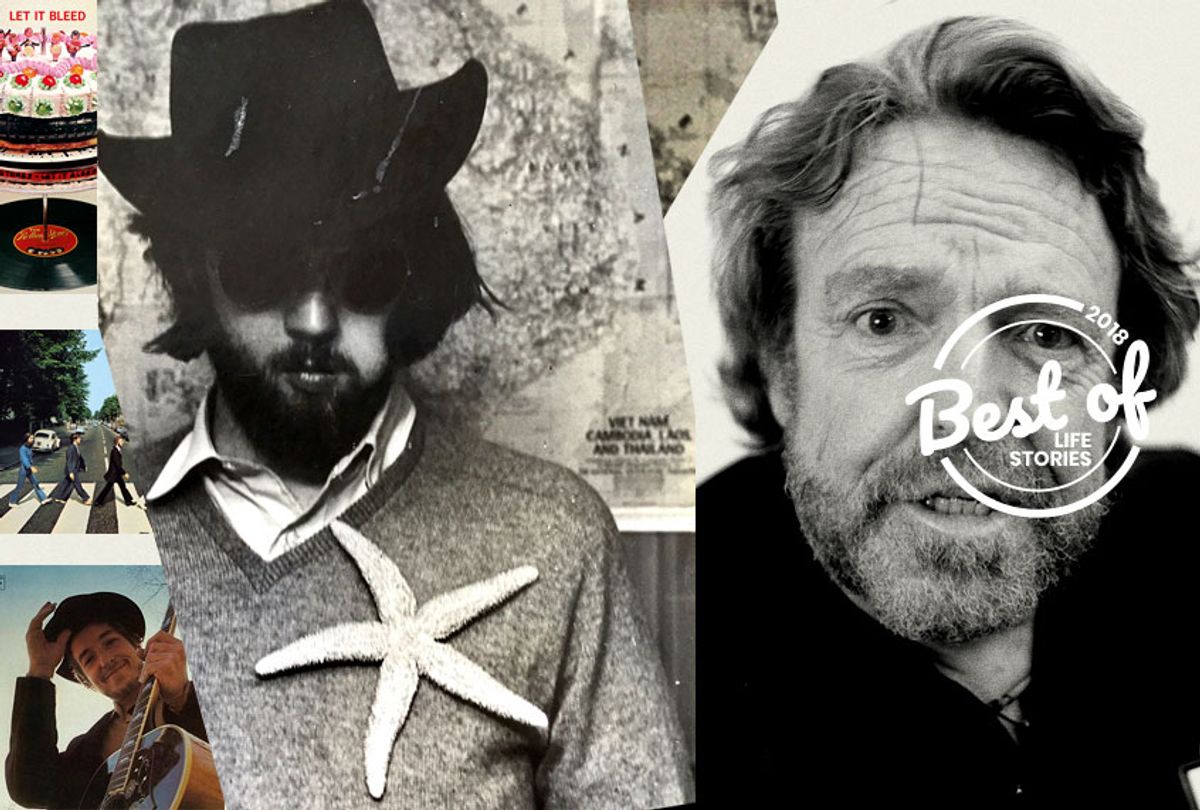

On a windy October night in 1969, John Perry Barlow blew into our rented house on the Connecticut shore like a blast from the past and the future too. Dressed as usual in a leather coat and cowboy hat, he had a suitcase and backpack he’d lugged all the way from India, through JFK Airport and straight up the highway to this funky summer cottage on Long Island Sound where he’d never been before. How did he even find the place?

He looked exhausted but also wild-eyed, preternaturally awake, with an “aha” look on his face that had nothing to do with homecoming or navigation. He shrugged off his pack and extracted a bronze, nearly-life-sized head of a Buddha. When he handed it to me, I almost dropped the thing. It was heavy. Solid bronze? The neck of it had been sealed over with some thick, dark substance that had hardened almost into a kind of cement.

Barlow rubbed his finger on the dark, sealed neck, took a whiff of it and handed it to me to do the same. I couldn’t smell anything, and that was the point.

“The Customs guys checked it out for 10 or 15 minutes, sniffing it, handing it back and forth. They finally decided not to bother," he said. "The guys who sealed this up for me assured me it would harden up and give off no smell. One of their main ingredients was cow dung.”

Barlow rummaged around in the kitchen for tools, knives, drill bits, a hammer. Then he whittled and chipped at the dark neck of the bronze head. The sealing material began to fall off in pieces. After a while he finally cleared out the Buddha’s neck, reached inside and pulled out a wrapped package that turned out to be a kilo of Nepalese black hashish in a thick braided bundle, just under a foot long. To pack it tight and keep the hash from banging around in the Buddha’s brain, Barlow had stuffed the head with flaky, reddish-brown Indian ganja.

I had never seen that quantity of hash in one lump before. The smell was exotic and outrageous. Barlow loaded a pipe with some ganja and whittled off flecks of the hash to sprinkle on top.

“Man, this is the strongest stuff I ever…” I said.

Barlow smiled and nodded as I turned into a mute stone statue.

And that became a ritual whenever anyone visited that house. Often in the very first minutes, Barlow would unveil his great meteorite of hash, encourage his guests to sniff it, and then chip off bits into his pot-filled pipe. And the reaction was invariably the same, sometimes with red eyes and coughing.

“Jesus, that is the strongest shit I ever . . .”

And then language would disappear in smoke as paralysis set in. Barlow would nod and confirm the time it had taken from first inhalation to complete loss of mental and motor skills. It became a kind of test, an initiation to this lost house we had casually agreed to share for a season.

Barlow and I knew each other from college. We were among the stoners, booze hounds, skirt chasers and well-read wise-guy layabouts who survived the Vietnam War with college deferments, and the dark tide of existential angst with the help of lysergic acid. Barlow always had more money than most of us and ran a kind of salon in his large, funky apartment in town, where the music ran hot and indulgence of all substances was encouraged. On any given night any manner of passersby and hangers-on might be on hand there in any frame of mind.

Barlow and I agreed to rent a house together away from most friends and traffic in order to get some writing done. When he went off to South Asia, I rented a summer house in a colony of empty cottages on Long Island Sound. Most places there were uninsulated and boarded up tight, but one doctor thought he might as well get money for his place instead of letting it sit vacant all winter. So he and I struck a deal for nine months, September through May.

It was a small two-bedroom, a few hundred feet from the water’s edge, sparsely furnished, but with a functional bathroom, kitchen and fireplace. To pay my rent I got a job as a daily reporter on the state desk of the Hartford Courant. I started out in a bureau on the shore, which was when I rented the house. But soon enough I had to report to work in Hartford most days, a 40-minute commute from our house. I had hoped to write fiction in my spare hours but my job took much more time and energy than I had imagined.

The doctor who rented me the cottage came by a few weeks later to check up on things. Barlow had not yet arrived and I hadn’t changed much of anything in the place. I was basically camping, only there long enough to sleep. I usually made myself breakfast but not evening meals. Everything looked OK to him, so he didn’t bother coming by again until spring. By then it was much too late.

A few days after Barlow’s return from India, a U-Haul truck pulled up to the cottage full of his stuff from storage. Like a magic box on wheels, it disgorged his 1250cc BMW motorcycle, a couple of ornate chairs, his stereo system and large library of LPs, an extensive wardrobe with many pairs of cowboy boots, various books and unassorted treasures including a huge Nazi flag, bright red with a black swastika inside a white circle. Neither an anti-Semite nor a violence-prone right-winger, Barlow must have acquired it purely for its shock value. He promptly draped it over the couch in the living room, where it remained.

One of the benefits of Barlow’s deep pockets was listening to great sounds as he went on a buying spree of the best music of the moment, artists and tunes I had never heard before, which played in that house over and over again all winter, until I knew them all and their order on the albums. "The Band" was a favorite, with its incredible harmonies and driving organ beneath and beyond the melody, the album photos making them look like 1890s members of the Wild Bunch, our co-conspirators in that mad, mad season on the shore.

A drawback of Barlow’s wealth, however, was his method of splitting expenses. I didn’t mind coughing up half the rent and utilities. But he posted a blank paper on the kitchen wall with our names on each side of a line down the middle. On his side he jotted prices of expensive steaks and bottles of whiskey, the kind of stuff I couldn’t possibly afford and seldom got to taste anyway, as JPB rapidly consumed what he bought. After some acrimony this practice ended.

We quickly fell into a kind of routine. I would wake up around 10 a.m., make coffee and stagger out to my car for the 40-minute drive to work. I would often work until the 11 p.m. deadline for the morning edition, grab a drink in town, and then drive back to our house, which would usually be percolating in high gear at the midnight hour. It was weird to enter the dark, silent suburb of shuttered cottages and then see the lights and hear the raucous party sounds — "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes" by Crosby, Stills & Nash was in rotation — coming from our place, the only open grave in the cemetery.

Anything might be happening and anyone might be there swilling booze, smoking dope, talking trash over the music, laughing and flirting if women were around. Any food on hand wasn’t fancy and didn’t last long. If we found something to burn in the fireplace we burned it, but wood was hard to come by since these were summer homes and none of us actually made much effort to buy any. Occasionally someone might stagger and fall against a table or chair. If the furniture broke, we most often fed it to the fire, with disparaging remarks about how tacky it was and how the landlord would never miss it. Despite the rudimentary insulation, the place stayed chilly and needed all the warming it could get.

Very often the hour grew too late and the visitors became much too impaired to drive off anywhere, so there were often crashers in chairs, on the floor, and for one lucky person (or two) a relatively comfy spot on the couch, though that was also under the Nazi flag. Instead of our attempted isolation providing peace for creativity, it merely created an inconvenient distance between our place and the rest of the so-called civilized world.

I would often have to tiptoe among the fallen on my way out to my car in the morning. I learned early on not to try to stay up with the all-nighters. The walls of that place were thin, so the music (cue: Bob Dylan's "Country Pie") and the conversation — not to mention the sex — was impossible not to hear. But stoned exhaustion was usually enough to knock me out, even on the craziest nights.

Barlow enjoyed hosting, however casually, and could be an amusing raconteur, though his stories almost always centered on himself. As long as I had known him, Barlow had a strong aspiration to be legendary in some way or another. He just hadn’t quite figured out how yet. He sometimes said he wished he was an old man — a strange desire, it seemed to me. But I think what he meant was that as an elder he would have the gravitas to speak and act from his no-doubt already-established legendary status. He and Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead were friends from boarding school and Barlow got the Dead to come to our small college to play high-energy, spaced-out open-ended concerts. But he and Weir had not yet started writing songs together.

One of his fanciful schemes was to host a Grateful Dead concert at his family’s ranch in Wyoming for free, to attract as many fans as possible. If half a million Deadheads showed up, as hippies did at Woodstock earlier that summer, the crowd would outnumber the citizens of Wyoming and could elect Barlow governor of the state, who could then proclaim new levels of freedom and license. Thus the chatter of Babylon, babbling on. Neil Young’s first album, released earlier that year, had an instrumental track called “The Emperor of Wyoming.” Coincidence? Definitely.

What we knew every minute of every day and night that year was that war was raging in Vietnam, a so-called “discretionary conflict” — unrelated to the defense or well-being of the United States — in which U.S. troops were torturing and murdering Vietnamese villagers and destroying their lands and in which we, as young men between the ages of 18 to 26, were expected to make ourselves available to participate in these atrocities. It was painful, criminal and outrageous.

And we were dedicated not simply to avoiding conscription into the Vietnam debacle but to protesting against it in any way we could.

It quickly became my mission as a daily news reporter to make the readers of the Hartford Courant eat the war for breakfast every morning with their cereal and coffee. I covered anti-war demonstrations and interviewed anti-war protestors as much as I could, often at Yale University in New Haven, a hotbed of Vietnam War resistance. I tried to find novel ways to approach war issues, like my interview with the Yalie heir to the Pillsbury Foods fortune who used his clout as a stockholder in companies making profits from the war to pressure them to change their policies. When Students for a Democratic Society held their convention at Yale around Christmas I lambasted them in print for their disorganization and internecine power struggles, which had rendered them impotent as an effective anti-war power.

Barlow and I and other friends drove to Washington for the Nov. 15, 1969, Anti-War Moratorium, still believed to be the largest anti-war demonstration of all, with an estimated half a million protestors on hand -- almost as many people as attended the Trump Inaugural. We drove down from Connecticut in my VW camper van, with tunes like "Here Comes the Sun" blasting, joints and booze passing around, picking up hitchhikers along the way, usually hippie types, but also one clean-shaven dude in a pea coat who turned out to be a pharmacist’s mate in the U.S. Navy. He had pockets full of pills of many colors and seemed to know what they were for or might do. As the driver, I had to refrain, confining myself to weed and booze for safety’s sake.

It was a wild trip through Manhattan and suburban Philadelphia to see friends, and a bit like a bus as people got on or off. Most of us made the entire journey to D.C., where it was a joyous relief to be among so many like-minded souls, all demanding U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam, immediate cease-fire and peace. Lots of smiling faces and good vibes and right-minded women. Heartening to feel that our tribe of peace-lovers was so numerous and strong.

Another memorable field trip later that same month was up to Boston Garden to see the Rolling Stones. Thanks to friendly connections we had good seats. B.B. King opened and he was truly incredible. We didn’t really want him to stop. But then the Stones tore the place apart, with lots of their hits up to and including “Let It Bleed,” another album we imbibed incessantly in our Connecticut summer/winter hideaway. At one point someone lifted a dwarf up on to the stage, long-haired and decked out like the rest of us, who had no arms or legs. His handlers leaned him against a Marshall amp. As Jagger danced and pranced up to and around him, and Keith Richards drifted often near the ecstatic fellow in apparent homage, making him part of the act. Also, in the audience, 15 or 20 rows back from the stage was a nearly seven-foot-tall man perfectly garbed as Abraham Lincoln.

The energy at Boston Garden that night was electric, kicking off the tour that would end in disaster weeks later in Altamont, California, where Hell’s Angels acting as “security” beat a man to death as Mick Jagger watched in horror from the stage. The documentary by the Maysles brothers, “Gimme Shelter,” is a spellbinding account of that tour and its tragic climax, that seemed in some ways invited by the Stones’ anarchic energy. The love-and-peace honeymoon between Woodstock in August and Altamont in December was brief indeed.

Barlow was supposed to be working on a novel he had started at college. Thanks to his Pulitzer Prize-winning mentor, novelist Paul Horgan, Farrar, Straus and Giroux had optioned Barlow’s partial manuscript for a thousand bucks, to be completed ASAP. In Barlow’s mythic memoir, he claims his option money was $5,000. But Barlow’s style was hyperbolic at the soberest of times. His bona fide accomplishments never seemed quite enough (to him) to impress people. So he gilded the lily at almost every turn. Thus his inflated novel option comes out to five times its actual amount. Maybe he believed it. One friend told him he needed a hyperbolectomy, which made Barlow laugh.

In his “fictionalized memoir” (is there another kind?), he claims he took “a thousand acid trips.” But even Barlow’s avowed good friend Timothy Leary probably never got close to imbibing that much, and he started years before JPB. Such consumption would require an acid trip almost every week for 20 years, or two a week for 10 years, a physiological improbability to put it mildly. Barlow makes other casual claims that ought to be marked in the text with HA! — short for Hyperbole Alert — such as being student president at a college that had no such office. Barlow was well aware of his tendency but did not think of himself as a liar, merely a fabulist. Caveat lector!

The trip to India had rearranged Barlow’s psyche. He was no longer the man who had written the opening chapters of a novel to which he could not now relate. Having no idea how to resolve that problem, Barlow embraced every possible distraction. For no good reason he came along to an interview I had with the author Norman O. Brown. And he consistently took his own drug consumption level one step beyond, shooting methedrine instead of taking it orally like the rest of us. He would boogie through an entire Taj Mahal concert or ride his BMW like a bat out of hell, letting the wind blow through his brain. He had been counting on early novelistic success to propel him forward on his quest for legendary status. Coming to terms with that impossibility must have been difficult for him, but he would soon find other venues in which to shine.

The long snowy winter made the summer cottage appear to float in a deep white vacuum. All the seasonal restaurants and stores were closed. No plow removed snow from the roads leading to our lost suburb. Marooned though we were, the party continued through the profligate winter into spring, when the melting snow turned the earth around us muddy and there came a reckoning of sorts. Feeling shell-shocked and feverish, having had my fill of what had become a grim psychic experiment, I quit my job and went to visit a woman I knew in a far-away place. So I was not on hand the day the landlord showed up.

When Barlow and others had asked me what kind of doctor he was, I’d said he was probably a dentist. That’s what he looked like to me, though I really had no idea. It turned out he was a psychiatrist. I was out of the country when the good doctor dropped by to visit his summer place. But the house was far from empty, or quiet, thanks to King Crimson. He must have been surprised to see several cars in the drive he didn’t recognize, along with a very large motorcycle. He called out my name, causing panic. The most urgent need was to remove all illegal substances from sight. One of our friends met the man outside in front of the house to stall his progress. Learning he was the landlord and believing him to be a dentist, our friend proceeded to open his mouth and ask about a troublesome wisdom tooth.

Puzzled and not pleased, the doctor hurried inside, where another of our friends dove on the couch and wrapped himself in the Nazi flag, though its identity probably did not escape the notice of this Jewish shrink. He also began to realize that, beneath the pile of filthy rubble in the kitchen sink and the strange “art” hung on the walls in place of his own kitschy souvenir collection and the slovenly rubble strewn in every corner, some furniture appeared to be missing.

He looked quickly into both messy bedrooms then hurried out behind the house, where another friend was trying to straighten up. At the sight of the doctor, this friend approached him pointing to his open mouth and mumbling an incoherent plea for advice. Red-faced and shaking with rage, but clearly outnumbered, our landlord beat a hasty retreat, out to his car and down the road, as full-blown panic set off a frenzy of people scooping up forbidden items, stuffing them into car trunks and back seats and driving quickly away.

Of course, Barlow overcame this minor setback on his otherwise upward trajectory toward his destiny. He would write lyrics to Dead songs, marry and have children, rub shoulders with the famous, declare cyberspace free and independent, help found several organizations promoting that freedom, become a Harvard Fellow and TED talker, divorce and find true (if doomed) love and generally morph into the legend he had always wanted to become.

Though a prolonged old age was sadly denied him, Barlow did enjoy decades as a sage. And his digital afterlife will no doubt live long and prosper. The breadth and depth of his obituaries, from the New York Times to the Guardian, from the Economist to Rolling Stone, and in various tech magazines, show that he succeeded in his ambition.

But there was one genuinely horrific bit of blowback from our winter on the north shore of the Sound. Our psychiatrist landlord -- always looking for more income -- worked for the Draft Board, vetting candidates for military service who seemed to have psychiatric problems. As we later learned from friends, the doctor inevitably asked these potential draftees, most all of whom were hoping to evade the clutches of the military machine, whether or not they knew Barlow or me. If they did, their interview ended abruptly and they were declared 1-A prime rib, ready to serve.

Though Barlow and I survived our time together and our self-imposed disorientation, others may have paid dearly for our careless pleasures.

And for that, and that only, I am sorry beyond words.

Shares