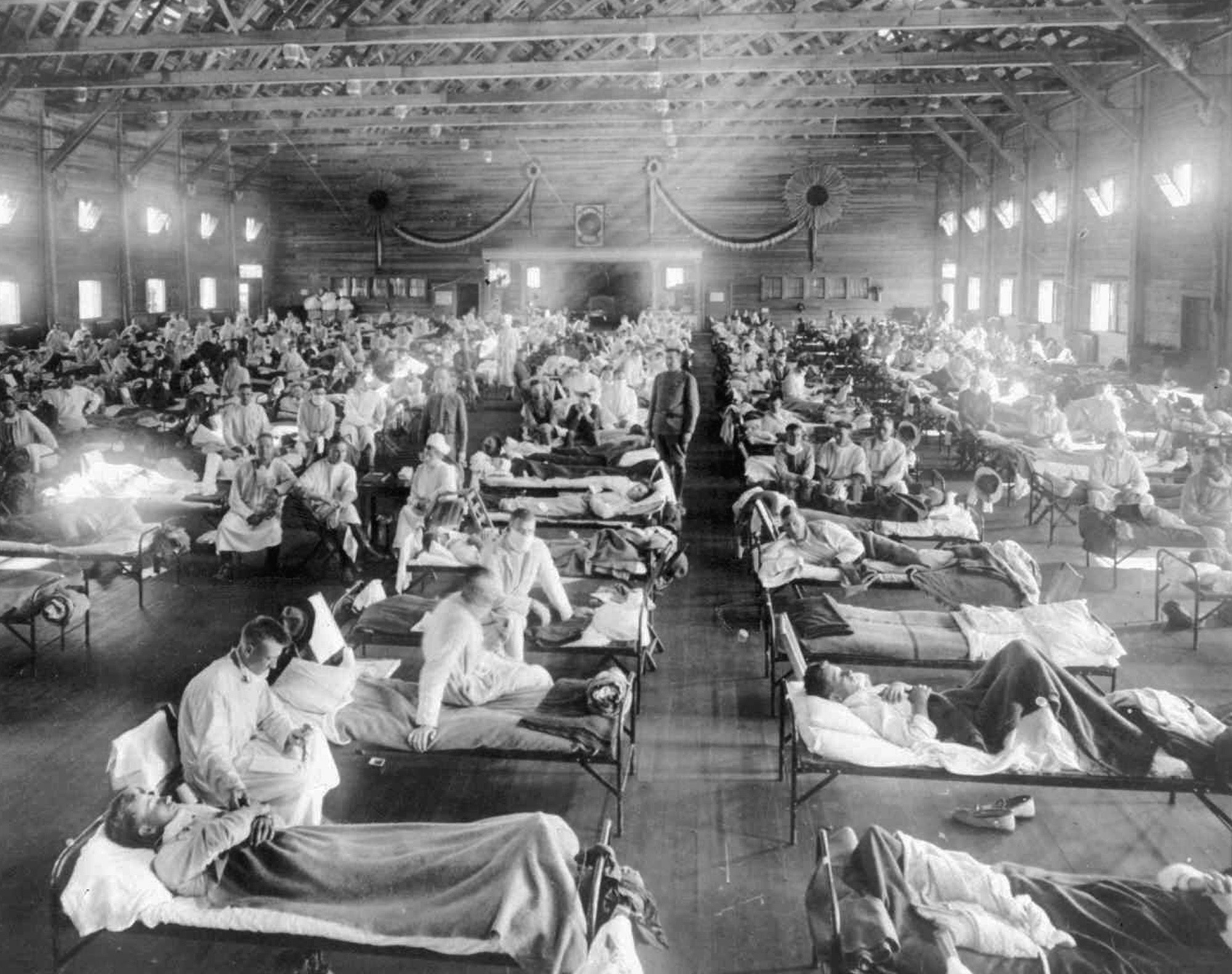

Flu season has officially begun, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and this year the infamous strain known as H1N1 is dominant. That’s the same strain that killed at least 50 million people and infected nearly one-third of the world’s population a century ago, between 1918 and 1920.

“Most flu activity so far this season is still being driven by H1N1 infections,” Kristen Nordlund, a CDC spokesperson, told Salon in an email. Nordlund added that “in the last four weeks, H3N2 viruses have been most common in the southeastern part of the country,”

To date, there have been seven pediatric deaths associated with a mix of H1N1, H3N2 and influenza B virus infections, the CDC states. It is too early to tell if H1N1 will infect a majority of those who get the flu this year, but it is worth asking: If it is, could it be as deadly as it was in 1918?

The short answer is no, and there are a few biological reasons why. First, Nordlund said, “influenza viruses are constantly changing,” which is one of the reasons why there is a new formulation for flu vaccines each year. In other words, the H1N1 strain from 100 years ago does not have exactly the same RNA as today’s H1N1 strain.

As the CDC explains, flu viruses can change in two different ways, with different consequences for infectiousness. First, there’s “antigenic drift,” something that happens in the genes of the virus over time as the virus reproduces. As a given virus spreads throughout one’s body, mutations develop slowly — meaning someone who has antibodies against a given strain may find that their immune system does not recognize the newer mutations from that strain, hence getting sick again from the same strain.

The second way in which a flu virus changes is called an “antigenic shift.” While an antigenic drift happens gradually, a shift is sudden and involves two strains merging genetic material, creating a new strain spontaneously. Antigenic shifts particularly can lead to a pandemic, because people have little protection from the genes of the new virus. In the spring of 2009, a shift happened with an H1N1 strain, according to the CDC.

Considering the 1918 H1N1 strain has undergone both kinds of change over the last 100 years, a 1918-like H1N1 would not “fit the current criteria for a new pandemic strain,” the CDC states. Hence, the probability of that exact virus re-emerging from a natural source is “remote.”

Another reason is that the current three-component flu vaccine includes protection against the H1N1-like virus. An outbreak at the high numbers that the early 20th century endured would be unlikely. If, in the rarest case, an 1918-like H1N1 virus did spread, there are a couple antiviral drugs that have been shown to be effective against it: rimantadine (Flumadine) and oseltamivir (Tamiflu). Hospital and critical care have also improved greatly since 1918.

Interestingly, CDC researchers successfully reconstructed the virus that caused the pandemic in the early 20th century. In this research they found the strain exhibited a “stark contrast to contemporary human influenza H1N1 viruses.” According to the paper published in Science in 2005, “the 1918 pandemic virus had the ability to replicate in the absence of trypsin, caused death in mice and embryonated chicken eggs, and displayed a high-growth phenotype in human bronchial epithelial cells.”

Despite being sequenced, there are still many questions that remain unanswered about the 1918 strain, such as where it originated from.

As for the future, researchers say every year it is likely a small number of healthy people will die from the seasonal flu, but across the world, it is the underprivileged who are most at risk.

“Because most of the world does not have access to the same level of prevention and medical care as developed countries, the greatest burden of any influenza pandemic can be expected to effect those least privileged,” researchers wrote in the journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. “Globally, environmental issues such as cold climates, lack of sewage systems, and lack of quality housing with amenities such as central heating are likely to contribute to excess mortality.”

Other researchers have gone so far as to predict that no influenza virus will ever reach a pandemic level comparable to what the world saw between 1918 and 1919.