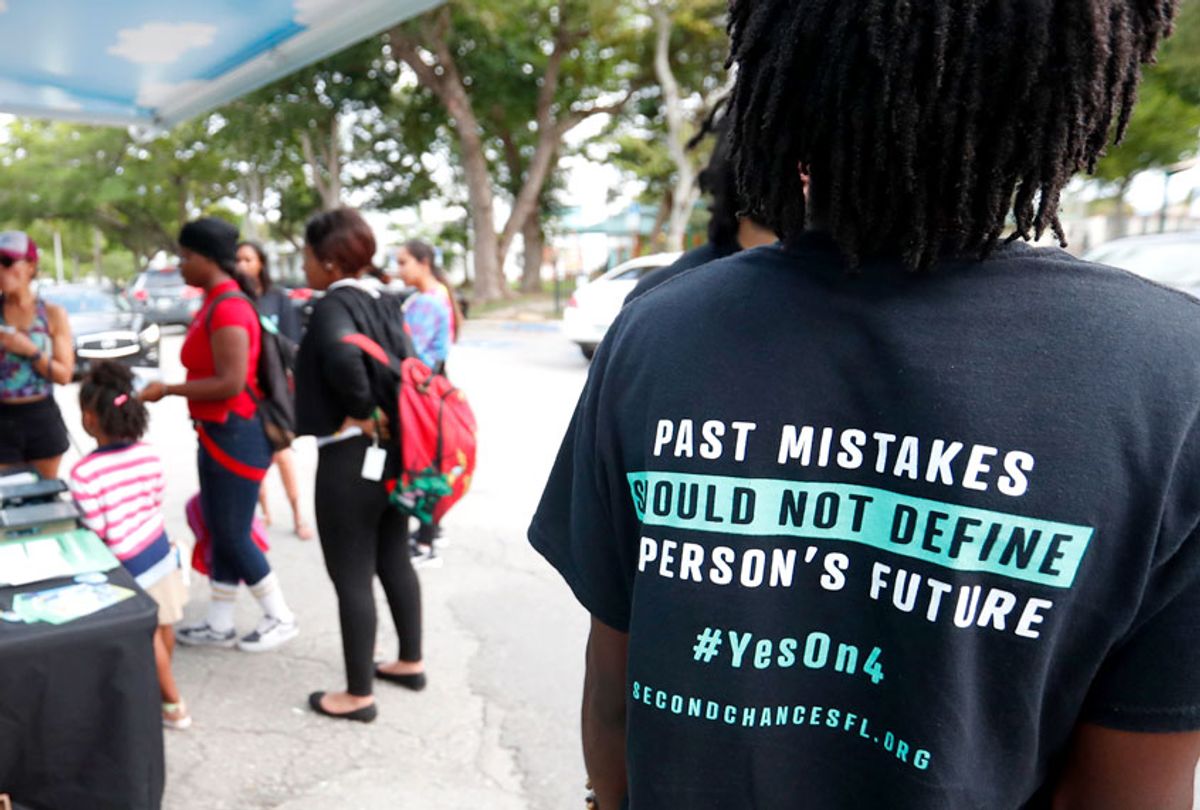

Tuesday was a historic day in Florida. Under an amendment overwhelmingly passed by Florida's voters in November, as many as 1.4 million Floridians with former felony convictions are expected to regain the right to vote. The landmark measure, known as Amendment 4, overturned a 150-year-old law that indefinitely disenfranchised those with felony convictions in the Sunshine State.

Amendment 4, which more than 64 percent of voters in Florida supported during the 2018 midterm election cycle, has been hailed as "one of the most significant voting rights act in Florida's history," according to the League of Women Voters of Florida, one of the proposition's main supporters. It will give most ex-felons in Florida who have completed the terms of their sentence, including parole and probation, the ability to register to vote either in person at their local elections office or online beginning Jan 8. The referendum does not apply to those convicted of murder or a felony sexual offense.

"The people have spoken. This is an amazing and incredible step forward for voting rights restoration," Myrna Pérez, the deputy director of the Voting Rights and Elections Project at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University, told Salon. "This is a welcome mat for folks who have been shut out of the political system for way too long."

Until now, Florida was the largest state to not automatically restore voting rights to citizens with prior felony convictions who had completed their sentences. Ex-felons who wanted to regain the right to vote had to wait a minimum of five years after completing any prison sentence and probation before they could apply for restoration with the state's clemency board, which included Florida's governor and three cabinet members. The clemency process was a longshot, as the Board of Executive Clemency had a backlog of more than 10,000 applications and met just once every three months, restoring an average of only 400 voting rights each year. The trying process and its backlog forced some people to wait more than a decade to have their voting rights restored and meant that only a small percentage of offenders ever received permission to vote again.

"Florida had one of the most restrictive policies in the country on rights restoration," Pérez said. She noted that, while there are a couple of states that have similar policies, "the impact in Florida, because of its demographics, because of the way its criminal justice system works, because of the sheer number of impacted persons — Florida's policy was the worst of the worst — even if its policy looked on paper like Iowa or Kentucky."

Steve Schale, a Democratic strategist who led former President Barack Obama's winning campaign to win Florida in 2008, explained that, while some may consider the passage of Amendment 4 to have been a long time coming, "The time that it took — while it might've been done earlier — it allowed a glowing bipartisan consensus to come together, which allowed it — when it actually did go to the ballot — to pass pretty easily. I don't know that if it would've passed in the same way if it had been on the ballot 10 years ago."

Despite what voting rights advocates consider to be a sign of tangible progress in Florida, political historian and American University professor Allan Lichtman told Salon that he does not expect the implementation of Amendment 4 to run smoothly, as some Florida lawmakers continue to debate how to handle the measure. Last month, confusion arose after Florida's newly-sworn in Governor Ron DeSantis, a Republican, argued that the measure should be put on hold until "implementing language" is approved by the state legislature and signed by him. That would mean at least a two-month delay in restoring voting rights, since the legislative session does not start until March 5. Meanwhile, a number of counties, including Miami-Dade, have elections or voter registration deadlines before then.

Amendment 4 is "not something that is happily received by the Republican-controlled government, and I would not be surprised to see efforts to impede, delay or undermine the process of integrating former felons into the political system" in Florida, Lichtman told Salon.

In an attempt to dispel the uncertainty that emerged last month, several election supervisors have said the language is clear, and they will register to vote eligible former felons who have completed their sentence until they receive guidance about how to manage this process. In addition, voting rights advocates have argued that, while "implementing language" could still come later, it is not required to register. In fact, according to Florida's constitution, new amendments take effect on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in January.

"Unless otherwise specifically provided for elsewhere in this constitution, if the proposed amendment or revision is approved by vote of at least 60 percent of the electors voting on the measure, it shall be effective as an amendment to or revision of the constitution of the state on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in January following the election, or on such other date as may be specified in the amendment or revision," the text reads.

Pérez, the deputy director of Voting Rights at the Brennan Center, stressed that the amendment voters passed was written clearly and in such a way that no additional debate is necessary. She encouraged eligible individuals with prior convictions to register to vote as soon as possible.

"It's very clear that the amendment is self-executing, and folks who are eligible should register and vote," Pérez said. "If they have any questions, seek counsel. This is an incredible victory, an incredible step forward and a welcome mat to folks who have been shut out of the political system for way too long."

Notably, the implementation of Amendment 4 could have implications that extend beyond the Sunshine State, as Florida is an election battleground, where presidential races have been famously decided by razor-thin margins. Former President George W. Bush won the state in 2000 by a margin of only 537 votes. Former President Barack Obama won with a slight advantage in 2008 and 2012. President Donald Trump won in 2016 with approximately 112,000 votes — a mere 1.2 percent margin over former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. With Amendment 4, some lawmakers and political strategists have suggested the political trajectory of Florida could be significantly and permanently altered.

"Even if only a small percentage of former felons register to vote, that could tip the balance in Florida's elections," Lichtman told Salon. "In the case of former felons, because they are so heavily African American, are likely to also be heavily Democratic." (Data collected by the Sentencing Project, a national nonprofit advocacy group, reveals that more than 1-in-5 Floridians who have lost their right to vote rights because of felony convictions are African American; another study found that the majority of felons, many of them minorities, tend to vote for Democrats.)

However, Lichtman continued, "It all depends upon the extent to which these former felons have a real opportunity to vote."

While Florida does not release data on the race of individuals who apply to get their voting rights restored, an analysis by the Palm Beach Post revealed that, under its previous Gov. Rick Scott, a Republican, "the system of restoring voting rights has for years discriminated against black felons." The Palm Beach Post found that, during his nearly eight years as governor, Scott "restored the voting rights of twice as many whites as blacks and three times as many white men as black men."

Still, Schale, the Democratic strategist, pointed out that those with former convictions who are now eligible to vote are a "cross section of Florida like any cross-section of Florida."

"They're diverse by race, by gender, by ethnicity, by background, by income," he continued. "It's not like these are a million Democrats. They're a million Floridians."

"The reality is: Florida is a really big, constantly fluid, dynamic state, where it's very difficult for any one thing on its own to change the dynamic of the state," he added.

Schale noted that it would be up to political groups and candidates to actively go out and mobilize these individuals to participate in the political process, register to vote and convince them to support their respective causes. He said this likely would not be an easy task, because the state has told people with prior convictions for decades, 'Your voice doesn't matter.' A lot of voters are rightfully frustrated with the process, so somebody is going to have to make the argument for why they should register to vote, and then somebody is going to have to make the argument of why they should vote for us."

In summary, Schale said, Amendment 4 is "not going to be organically driving partisan change."

"In reality, in a state that's divided as closely as Florida, everything matters and nothing matters," he continued. "Nothing is happening in vacuum. . . . The state is too big, and there's too many things happening to ever say this one thing is going to upset this very narrow, stable closeness that we have now."

Casey Klofstad, a political scientist at the University of Miami, appeared to echo Schale as he explained, "In a razor thin race, you can explain [the outcome] with everything, and therefore you can also not explain it with with anything." But, he pointed out, "While this is a large group of individuals — many of whom probably have a liberal, Democratic leanings — the question is: Will these individuals re-enfranchise themselves?"

For now, Klofstad said, the impacts of Amendment 4 on Florida's super-tight elections will be "small and incremental but could, theoretically, grow over time."

Shares