When New York and Chicago decided to expand their public bike share systems a few years back, city officials wanted to go about it democratically. Using community meetings, workshops and interactive maps, they asked the public where they wanted new bike stations to be built.

“I have consistently found that local neighborhoods know their area better than anyone,” Joseph R. Lentol, a New York State assemblyman from Brooklyn, said after city officials in 2014 announced a major expansion of New York’s year-old Citi Bike system.

The Chicago Department of Transportation also thanked residents for their input in locating the 175 new bike stations it added in 2015.

“Chicagoans gave great suggestions for the locations of new stations, and we look forward to placing them where they were requested,” Transportation Commissioner Rebekah Scheinfeld said.

Ultimately, though, just a fraction of the docking stations were built in the places recommended by the public, according to our new research on participatory bike share planning in Chicago and New York.

Demands ignored

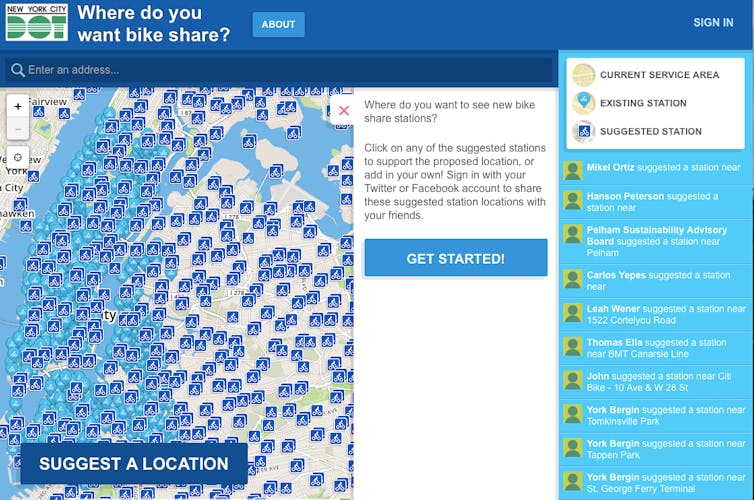

New Yorkers suggested 2,000 sites as locations for new bike stations in their city, using the transportation department’s interactive online map. But our study, published in the Journal of the American Planning Association, shows that just 5 percent of bike docks built during the 2014-2015 expansion are located within 100 feet of suggested sites.

Chicago was slightly more responsive. Ten percent of docking stations built through 2015 were located at or near the spots residents identified on the interactive map.

Our findings don’t imply that city officials weren’t listening. There are practical reasons why they weren’t able to put most bike stations where people asked.

Public bikes — a quick, green way of getting around town — are designed to complement buses and subways. So enlarging bike systems in New York and Chicago meant assessing gaps in each city’s transportation network. The results of that analysis may conflict with people’s desires about where new docks should be installed.

NYC Dept. of Transportation

Transit planners would also have disregarded suggested dock locations that lacked sidewalk space, or were too close to fire hydrants or utility services.

Cities often face resistance when building bike stations, too. Docks can take away coveted parking space, outraging drivers. In some historic districts, residents and planners see bike docks as incompatible with the atmosphere.

Despite these challenges, officials tried to ensure equal access to the new bikes.

“What I’m shooting for is uniformity across every neighborhood,” New York’s bike share director, John Frost, told residents at a community meeting in 2015.

Differences between neighborhoods

Perfect uniformity is impossible, though. In both cities, we found that the government’s responsiveness to public input varied by neighborhood.

New bike stations in and around downtown Chicago were far more likely to be sited where suggested than those in more suburban areas: 12 percent versus 6 percent. This could be because stations on the outskirts of a system generally are used less, and so are not built as densely as cyclists might like.

The National Association of City Transportation Officials guidelines say that residents of a neighborhood served by bike share should live within a five-minute walk of a docking station.

In New York, 9 percent of new docks in outerlying boroughs were built where residents asked. In the city’s financial core of Manhattan, just 3 percent of new docks were — likely because people requested more docks in areas of Manhattan already served by bikes, while city officials wanted to expand into new neighborhoods.

Neither city offered much guidance on these issues for people who went online to suggest locations for new bike stations. So residents just dropped their pin where they thought a dock would make most sense.

New York and Chicago are not the only cities to ask people for input in creating or expanding bike share only to end up with final plans that don’t necessarily reflect it.

Cincinnati, Ohio, used an interactive online map as part of a feasibility study in 2012 to guide the launch of its bike share. Planners got way more information than they could use: People suggested 330 sites for bike docks throughout the city, across the Ohio River and even into Kentucky.

The launch called for just 29 stations.

Lessons for democracy

The implications of our study go well beyond bike sharing.

Cities must frequently decide how to distribute scarce public resources like low-income housing, transit stations and parks. The experiences of New York, Chicago and Cincinnati offer useful lessons for cities hoping to engage residents in decisions that affect their neighborhoods.

All three made great efforts to gather input on locating new bike docks. But it might not appear so, given that just 5 or 10 percent of suggestions were implemented in the end.

With trust in government at historic lows, that could make people even more cynical. They don’t know whether requests for public input are genuine or just a show of democratic process — and a waste of time.

But our study found some positive results from the consultation process around bike shares in New York and Chicago, too.

The online maps enabled residents to take direct action in planning their cities, rather than just commenting on the ideas of planners — or waking up to discover a docking station had been built outside their door.

As recent urban planning research confirms, this kind of transparency — the online maps, community meetings, workshops and the like — also gives decisions more legitimacy.

It also leaves a record, allowing researchers like us to measure and evaluate the results. Understanding where and why people’s ideas were disregarded can be a learning experience for residents and governments alike.

Ultimately, our study finds that cities wanting public input on big decisions must not only engage residents effectively — they must also explain the constraints they face. That helps residents make informed recommendations that are more likely to be implemented.

Locals know their neighborhoods best. We believe cities that really listen will find the best solutions to urban problems.

Greg Griffin, PhD candidate, University of Texas at Austin and Junfeng Jiao, Assistant Professor of Community and Regional Planning and Director, Urban Information Lab, University of Texas at Austin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Shares