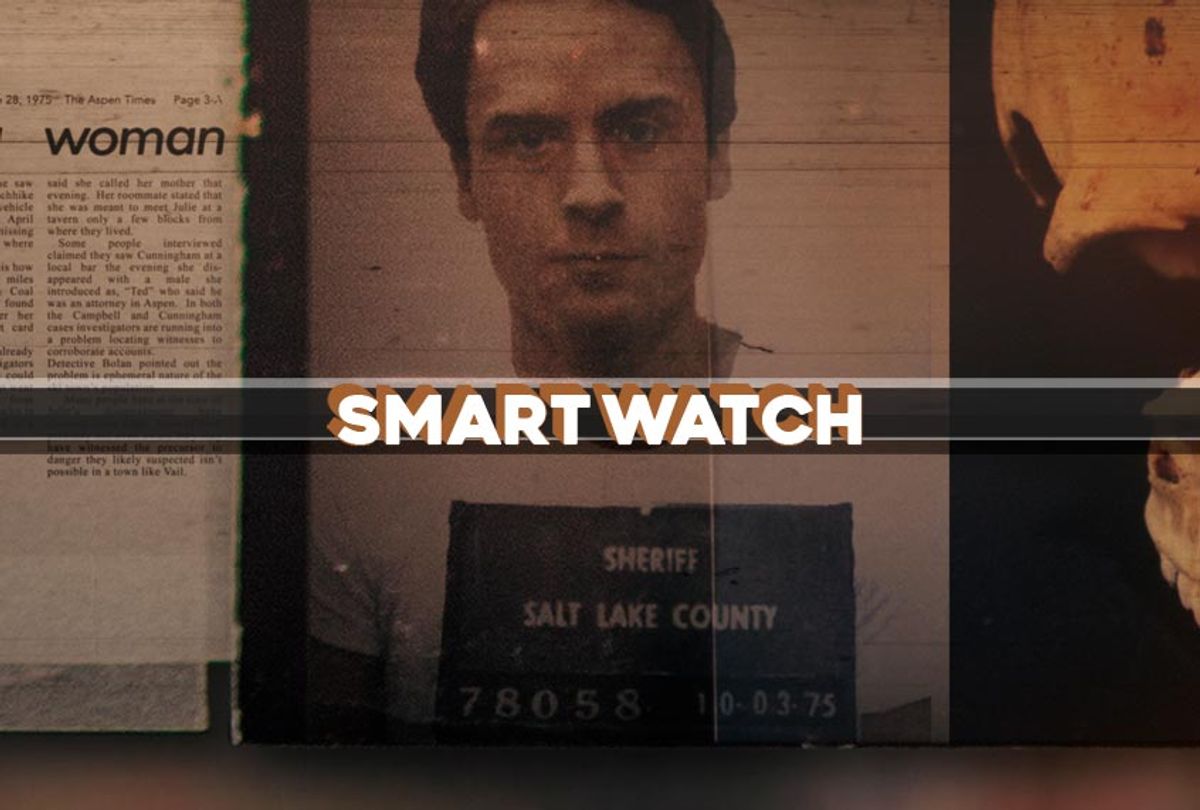

“Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes,” currently streaming on Netflix

Ted Bundy is to true crime what O.J. Simpson is to the 24-hour news cycle — which is to say that although both formats existed long before these men were tried in the legal system and the court of public opinion, each brought out a queasy fascination in us that shifted their respective mediums irrevocably.

The how and why of each man’s influence differ greatly. But they held two qualities in common that go far in this world: they were charismatic and handsome.

“Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes” is a multi-part examination of how much latitude and rope the world extends to a charming man. None of the subjects featured in the series explicitly say this, but time and again that notion pops up in the form of disbelief and frustration at what you’re seeing.

Here is a man who decapitated his victims, who moved some of them to places he could visit time and again to violate their deteriorating flesh over and over. But his smiling eyes and wit made cops comfortable enough to leave him alone in unsecured spaces, enabling him to escape and hide for days the Colorado hills.

In Florida, he smooth-talked a judge into giving him more desirable quarters and a pliant media into laughing obsequiously as he gleefully likened what was expected to be a string of trials for homicides and rapes to a season of sports.

Bundy may not have been academically gifted, but he was well-spoken and clean-cut, smart enough to inveigle his way into positions of power and trust, and enough of a narcissist to create a public profile for himself long before he became the Jack the Ripper of the 20th Century.

And that is more than enough to gain a person sympathy, trust and a second chance in America. As one subject says, “He didn’t look like anybody’s notion of someone who would tear apart young girls.”

Netflix strategically released “Conversations with a Killer” on Thursday to mark the 30th anniversary of Bundy’s execution, not that any but the most devoted followers of this case would make that connection without, say, turning to Wikipedia for a reminder.

The audio clips featured in the series were culled from more than 100 hours of interviews recorded by Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth in 1980, who went on to co-author two books based on the content, 1983’s “The Only Living Witness” and the follow-up upon which the series is based, “Conversations With a Killer,” in 1989.

Intertwining news footage, crime scene photos and period-specific stock images quilt the segments used in the series into a more-or-less linear narrative that can easily be digested in one sitting.

Beyond that, however, the series is far less of a ground-breaking addition to the modern true crime genre than, say “The Keepers” or “Making a Murderer,” titles about cases made famous by the exposure Netflix generates, hooking audiences with unexpected reversals and twists. In the wake of these, the contents of Ted Bundy’s serial killer file, though ghoulish, also happens to be fairly common knowledge.

Nor, for that matter, do his monologues describing how he committed various murders and what he did with the bodies hold much of a creep factor. Bundy does so in the third person, in order to make it seem hypothetical, an outcome of Michaud’s strategic appeal to his intellectual vanity when he refused to take responsibility for the murders. But in a time when lying and refusing to take responsibility is a common feature of privileged men absolved of wrongdoing, the effect is less unnerving than it is aggravating.

Ultimately, “Conversations with a Killer” isn’t primed to make a person’s skin crawl. Unless the viewer is on the younger side and unfamiliar with Bundy, it contains no surprises, either. This isn’t the series’ fault, but a feature of time and entertainment trends. Viewers have access to all we can handle via non-stop murder re-enactments on Investigation Discovery and Oxygen, and women-in-peril popcorn flicks on Lifetime.

And these are products in part born of the public’s disturbing preoccupation with Bundy, seen in real-time as young women flocked to the Florida courtroom to watch his trial.

“Conversations with a Killer” shouldn’t be dismissed, either. Once the series walks us through Bundy’s grisly crimes, processing the details of his serial murders, rapes, torture sessions and necrophilia, what we’re left with is a story of a sociopath and narcissist who seduced a nation through the camera lens. Experiencing on a visceral level what that has to teach us about who are has worth.

Millions of us lapped up Bundy’s mesmerizing duplicity as a diversion. Worse, law enforcement officials and the judge overseeing the Florida trial in which he would eventually be convicted of but a few of his crimes enabled it.

News organizations fell all over themselves to chronicle every moment of his trial in Florida for two murders and several assaults at the Chi Omega sorority house on the Florida State University campus. And the judge, who allowed the proceedings to be filmed, did little to curb Bundy’s tendency to grandstand and showboat for the cameras, effectively making it impossible for his legal team to mount a defense.

In the end, Ted Bundy was sentenced to death and executed 30 years ago this week. The bad news is that enough of us were taken in by him to create a market for stories like it, both in TV news and in entertainment.

“I Am the Night,” premieres Monday at 9 p.m., TNT

With enough remove, the grisliest of crimes takes on the aura of cautionary fairy tale, as is the case of Elizabeth Short. The aspiring actress is remembered not by her talent but her gruesome end: death transformed Short into the Black Dahlia, one of the ugliest unsolved homicides of Hollywood’s post-War era.

The Black Dahlia legend lives in modern times by way of James Ellroy, whose novel inspired a Brian de Palma film so abysmal that I have personally stopped people from renting it several times as a public service.

Knowing this, the bar that Patty Jenkins’ limited series, set in 1965, has to clear is only about kitten-heel height, and it’s a relief to report that she flies over it. Having said that, “I Am the Night” benefits from not being expressly about the Black Dahlia murder itself but the Hodels, a family commonly linked to her demise, by way of Fauna Hodel (India Eisley).

And the story of Fauna’s biological family is one of those crazy yarns that defies fiction, so unreal that the reporter who nearly discovers the truth about the Hodels, Jay Singletary (Chris Pine), is soon ruined by the family’s politically-connected paterfamilias George Hodel (Jefferson Mays).

Fauna was given away at birth to a black woman in Reno, Nevada, and told that her mother is a white teenager and her father is black. But the woman who raises her keeps the true story of her parentage a secret until, in a drunken outburst, she lets the truth slip out. Soon enough Fauna heads to L.A. hoping to meet her grandfather George, unaware of his libertine hobbies and fondness of Grand Guignol-style spectacle.

Sam Sheridan bases his script of a heavily fictionalized version of Fauna’s autobiography, using Pine’s character and the Black Dahlia case as a way-in to a twisted story about lust and family insanity that ends up substituting the pursuit of one mystery to the unraveling of another. And by the time you come to realize that the hook is the dangerous eccentricity of Fauna’s quest, you’re in too far not to hang on for the denouement.

Jenkins’ direction allows space for Pine’s performance to muscle through any holes and shortcomings in “I Am the Night,” while Eisley’s grace and silence convey the threat of the Hodels’ menace. As it comes together, the final cut isn’t quite a bleeding-edge thriller so much as a visually sumptuous, slightly filthy noir attraction that doesn’t necessarily shed outrageous new light on a vintage mystery. But it succeeds in elevating the best in the talent resurrecting a piece of it, proving that with enough time, even the gruesome displays of humanity can be rendered into ethereal distractions.

Shares