President Donald J. Trump is stuck in a frustrating contradiction -- and his intractable government shutdown pulled the rest of us along to suffer it with him. To assuage his “base” by evoking a barbaric aversion to immigrants, Trump demands a wall along America’s southern border. On this point, he refuses to budge, save by restoring immigrant protections that he himself revoked. That supposed offer to end the shutdown was one Trump expected Democrats to accept, for he surely wouldn’t open the government first.

No preconditions in Trumpian deals: it is his way or the highway, and the highway must lead to a wall. Anything less would make him appear the worst of all possible things, weak. And dominant men – like the barbarian chieftains of old – must never appear weak. Yet his self-proclaimed artistry of the deal, Trump’s purported prowess at persuasion, nonetheless failed to impress his chief opponents, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer. For them, Trump’s demand was eminently refutable.

So, Trump blinked, at least for three weeks, while the country waits to see if the big man shuts down government anew. It is worth pausing a moment to think about these confusing Trumpian self-projections. Such pause will not break the logjam, but it may help us to better see its roots and implications.

Donald Trump likes to boast of two rather distinct images of himself. In one he proclaims his mastery of salesmanship, his uncannily clever skills of negotiation and bargaining. In the other, he struts about announcing his formidability as a consistently triumphant street fighter, a master of bellicosity, aggression and combat.

It is not often enough noticed that these self-portrayals are inconsistent, to the point of being mutually exclusive. The shrewd seller, after all, succeeds by equivocation, with smooth talk and a knack for duplicity -- predatory purpose masked by easygoing amiability. Amiability is not a warrior virtue. The master of combat may deploy a strategic feint to create confusion on the battlefield, but his ultimate goal is unambiguous physical destruction of an opponent. Fighters kill, they don’t connive.

In short, Donald Trump wants us to believe two things at once: that he is a supremely effective salesman and that he is a warrior king who knows more about war than his generals. Trump’s claim to salesmanlike skill – were it authentic - would be supremely helpful in the contests of democratic politics. Democracy is all about mutual efforts at persuasion. But persuasiveness is utterly irrelevant to the warrior ideal. The talent for slaying opponents is a barbaric necessity, but it has no place in a democracy.

Trump’s fuming in the White House, boxed in by his self-crippling paralysis of motives, reflects nothing so much as his incapacity to reconcile his psychic needs to project both salesmanlike affability and prehensile domination. Trump is, of course, less likely to reflect on such tensions than to experience their frustrating duality. But since he has the power to inflict his frustrations on the rest of us, it behooves us to better understand their sources, especially when much of conventional thinking seems mystified by the Trump phenomenon.

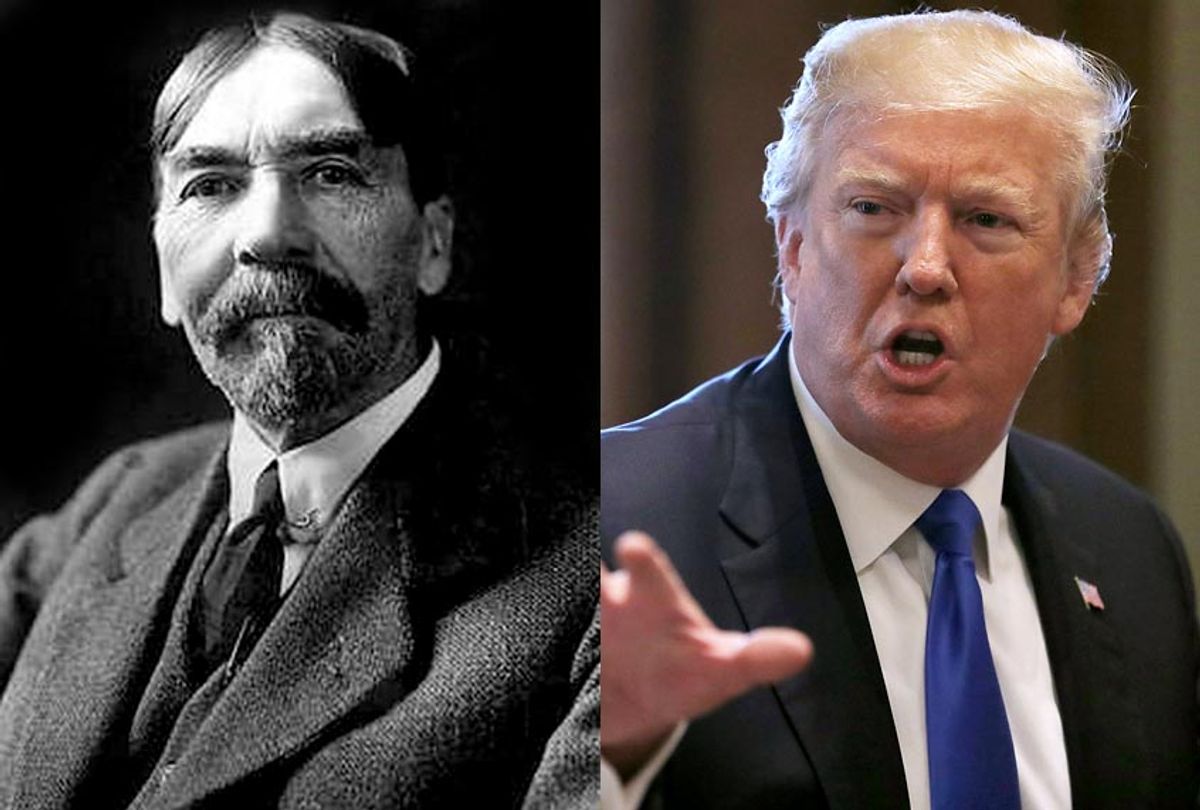

For such understanding, the classic tradition of social theory offers a valuable guide, the often overlooked American radical, Thorstein Veblen, the Progressive Era economist and sociologist and author of "The Theory of the Leisure Class," a landmark work published in 1899. Veblen has a peculiar value as interlocutor in the conspicuous case of Donald Trump. This is because his critical theory anticipates just the kind of awkward duality embodied by our pugnacious president. A brief sketch will help to underscore the point.

Veblen held that much of recent human history, a history stretching back millennia to the current moment, bears the militant stamp of barbaric warrior culture. The legacy of such enduring barbarism assigned high masculine value to predatory physical dominance, to proud display of a “strong hand.”

Most important, its martial habits and ideals encouraged “an habitual bellicose frame of mind,” a tendency to judge people, situations and events from the singular standpoint of a deeply felt cultural need to win fights, and especially to affirm the evidence of such victory in conspicuous tokens and icons of successful slaughter. Skulls, bones and hides once did nicely for the purpose, and so did female slaves. Such were the praiseworthy rewards and symbols of the barbarians’ presumed “propensity for overbearing violence and an irresistible devastating force,” qualities that Trump preens to project at every public opportunity.

Now, in what passes for liberal democratic America, Veblen saw that the exhibition of barbaric virtue is constrained, though far from prohibited. Football’s brutish violence is supposed to stay within the bounds of the gridiron, for example. The bellicosity of mass entertainments like "Game of Thrones" are fabricated spectacles of medieval brutality, a parade of mayhem, rape and destruction whose popularity suggests a disturbingly real cultural fascination with a dystopian reversion to hell. Trump is our snickering King Joffrey grown old, tiresome and fat.

Veblen’s point was that American culture and American power have evolved beyond adolescent tough-guy fantasies, or rather that its culture has reshaped, adapted and changed such fantasies, lending them new, more civilized form. Predatory success is for us supremely displayed less by skulls, hides and slaves than by conspicuous possession, the rewards of mastering unruly financial markets.

Today’s barbarians are well-suited, mannerly and astute, especially at shrewdly gauging the ebbs and flows of digital capitalism. They are manipulators of the insightful bet, risk and hedge. They wield illusory credits and debits, pecuniary symbols of wealth, all the better to club their opponents into a politer businesslike submission.

The dark arts of modern finance, suggests Veblen, have American roots in the fraudulent arts of rural real estate hucksterism. This venerable institution, a mainstay of America’s 19th-century country towns, made land selling a game as popular as poker. Its goal was as simple as it was predatory: to extract “something for nothing from the unwary, of whom it is believed by experienced persons that ‘there is one born every minute.’”

Indeed, it is just this salesmanlike prowess at fraud that Trump celebrates with his evocative oxymoron, “truthful hyperbole.” Yet for all his entrepreneurial boasting, Trump seems helpless to resist the appeal of its earlier more violent expression, a wish for martial domination so overwhelming and unchallenged that it contaminates his equally cherished reputation as dealmaker par excellence, the very virtue he most needs if the government is to remain open. This is Trump’s predicament, and ours: His Democratic opponents will understandably not “deal” with a president who insists that he must “win.”

Caught between his aspirations to dominate and to deal, Donald Trump embodies the arrested state of spiritual development of a bollixed culture. America wants it both ways, to wallow in the pugnacious and malign masculinity of triumphant aggression while aspiring to a late barbaric maturity that welcomes considerably more peaceful ways of pulling the wool over people’s eyes.

Meanwhile, if things weren’t confusing enough, reason, science, civility and common sense encourage tens of millions of Americans toward a critical bent that favors democracy and rule of law, a political order that authenticates neither fraud nor force. America, suggests Veblen, along with much of the ostensibly modern world, is caught within the throes of a profoundly conflict-ridden effort to synthesize some workable form of barbarism, capitalism and democracy.

The case of Donald Trump shows how painfully hard it is to fuse barbarity, fraud and democracy within the singular institution of the presidency; how much harder is it to achieve at the level of a whole society. Our current predicament is a mirror of these swirling and discomfiting tendencies. Just think of it: A 21st-century democratic government shut down over an atavistic wall by a chief executive unable to decide whether he most wants to be maker of deals or the archetype of bellicosity. Donald Trump is the nation’s problem, but the contradictions he embodies are America’s too.

Shares