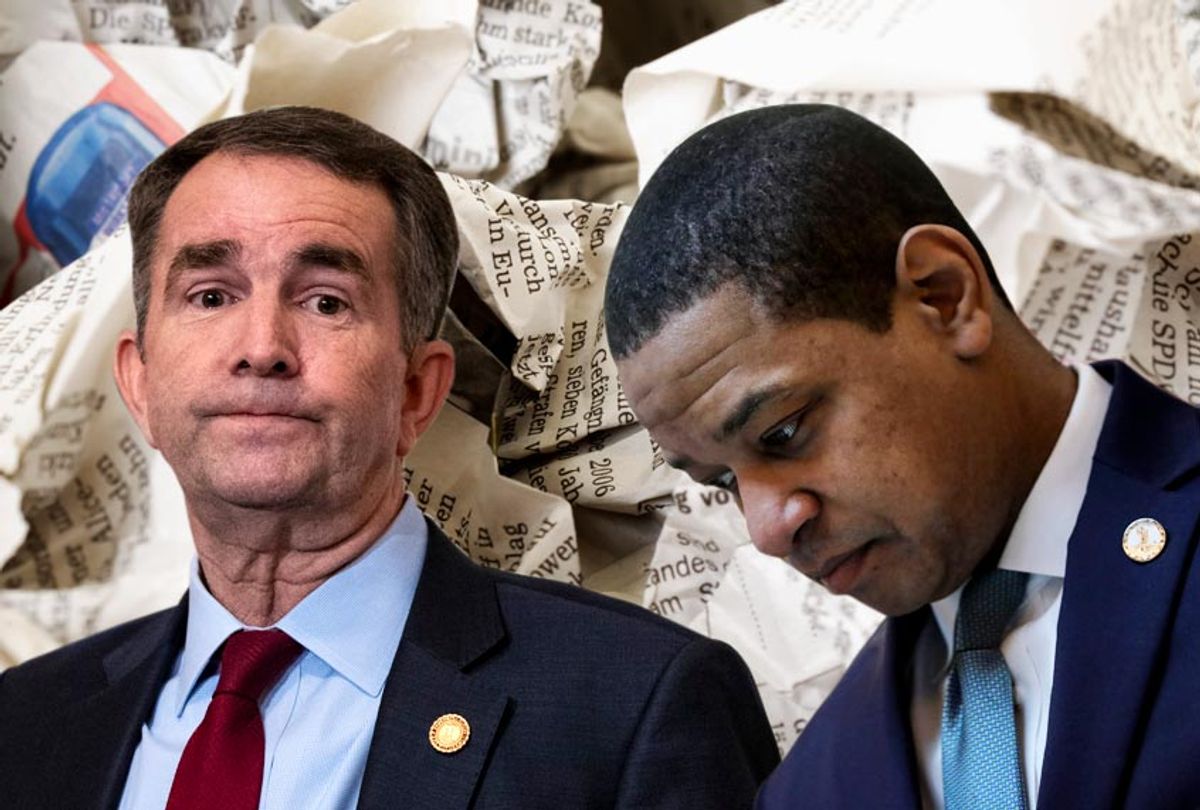

There's much that's astonishing about the enormous scandal consuming Virginia politics right now, in which the Democratic governor and both of the Democrats behind him in line of succession are embroiled in what may be career-ending scandals. Blackface photos, sexual assault allegations, the threat that Gov. Ralph Northam might moonwalk in public: It's by turns terrifying and ridiculous. But perhaps the most astonishing part, for most people involved or watching from afar, is this: How it can possibly be that all three of these Democratic elected officials -- the top three in a middle-sized state right next to the nation's capital — are confronting these scandals all at once?

Well, experts in journalism say, buckle up, because things are likely to get worse. The Virginia scandal is a reflection of a larger trend where politics will be driven more and more by revelations, gotcha moments and resulting scandals. The decline in robust, in-depth journalism, particularly on the local level -- coupled with the rise of social media and well-funded partisan opposition research -- is creating an atmosphere where political scandals, legitimate or not, will increasingly dominate politics and media.

"You have this degradation of resources in local journalism, which has been going on for a while now," said Joshua Benton, director of the Nieman Journalism Lab, which is currently offering a fellowship for local investigative journalism. "You also have this counterpart, which is that it’s easier than before for opposition researchers on all sides to dig up dirt of this sort."

The decline in local journalism means that politicians in the early stages of their careers, when they're running for school board or city council, "are not getting anything like the sort of attention they would have gotten when there was a reporter whose full time job" was to cover such institutions or such elections, Benton said.

Philip Napoli, a professor at Duke University's Sanford School of Public Policy, added that this trend has coincided with another, "the rise of social media and the ways that political candidates are able to communicate with their constituencies directly" and present a version of themselves that's more to their own liking.

The result is that politicians simply don't get the vetting they might once have received as they climb the career ladder from smaller offices to statewide and even national offices. Red flags that might have been noticed before a politician reached a position of significant power get overlooked, because local papers simply don't have the resources to catch them.

That doesn't mean such skeletons will remain in the closet forever. As both Napoli and Benton pointed out, the decline in local journalism has accompanied a corresponding rise in partisan blogging and well-funded opposition research, conducted by those with a strong incentive to dig for dirt — especially once a politician has risen to major office.

In fact, one could argue that the decline of local journalism, which tended to focus more on facts and policy issues, has created a vacuum that's being filled by websites driven by an overtly political agenda and, in many cases, a loose relationship with the facts.

In the "old model," Benton said, people who wanted to share damning information like sexual assault allegations or past episodes of racist conduct would "go to a reporter and hand him or her the documents or the evidence," and that reporter would "determine whether the information that’s being handed to them is correct or not."

"Now, increasingly you can just post it online and skip that step in the process," he added. So questions about whether the information is true and legitimately newsworthy don't get answered in advance.

The Virginia case offers a good example. The blackface photo from Northam's medical school yearbook has always been there. But it wasn't a reputable journalistic outlet that leaked it, but a shady blog called Big League Politics that has been less than honest about its sources of funding. The same site also elevated the sexual assault allegations against Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax, which first appeared in a social media post. In both cases, real journalists scrambled to play catch-up to determine the truth of the allegations before they spread too far.

In these particular case, the information turned out to be legitimate: The blackface photo was on Northam's yearbook page (although he denies being in it) and a woman named Vanessa Tyson has accused Fairfax of a 2004 sexual assault (which he denies). But in many other cases in the past, stories like these have spread rapidly and done massive damage before eventually being debunked.

For instance, Breitbart pushed a false story accusing the nonprofit ACORN, of being involved in sex trafficking, which dominated the news cycle and led to the group's collapse even though it was entirely untrue. An effort to accuse Planned Parenthood of selling "baby parts" from aborted fetuses had a similar cycle — the lie was spread widely, and media organizations reported the story before all the facts could be gathered. Many conservatives either still believe this or pretend to, which has led to repeated efforts to withdraw all government funding for Planned Parenthood.

Those stories took off because of manipulative or misleading editing of video evidence. Napoli worries that false stories will continue to get worse "because the technology is there" to fabricate evidence from whole cloth.

"At some point, it is going to happen," he said, speaking of a hypothetical Northam-type incident. "It is going to be the case that the entire yearbook photo was fabricated."

To make it worse, Napoli continued, "Hyper-partisan news and disinformation can actually play a role in setting mainstream news agendas. What remains of our legitimate news outlets, as under-resourced as they are, are more vulnerable" to stories that may not be true, or are unimportant, or are being spoon-fed to them by opposition researchers.

We've already seen this happen, to dramatic effect, in the 2016 presidential campaign. True but unimportant stories, like those about Hillary Clinton's email server, or flatly false ones, such as those about her nonexistent health problems, got outsized coverage. Meanwhile, legitimate and important stories about Donald Trump's ties to Russia and his lengthy history of corruption got only a fraction of the coverage.

Money played a big role in that. There were well-financed interests driving the fake scandals about Clinton into the media bloodstream. Meanwhile, investigating Trump required significant resources that news organizations had to pony up themselves. Some did so, of course, but many simply didn't have the staff or money to do the digging.

Take that dynamic and multiply it for local and state media, where newspapers are in an even steeper decline and partisan operators who don't much care about sourcing or accuracy can launch a blog and start firing off accusations willy-nilly.

To be clear, in Virginia, these scandals are based in truth, and are important. But this is all happening in the worst possible way — all at once, and in a fashion clearly intended to subvert the expressed preference of Virginia voters for Democratic leadership — which makes clear why it's a big problem that legitimate journalism is in decline while partisan scandal-mongering is on the rise.

No one is properly vetting politicians before they rise to positions of power. Stories are breaking and spreading before the facts can be properly assessed. Confusion reigns and voters have become increasingly distrustful of any story — no matter what the source or the facts — that doesn't come from a perspective that they are sympathetic with. The problem isn't just Virginia; it's everywhere. And there are no obvious solutions in sight.

Shares