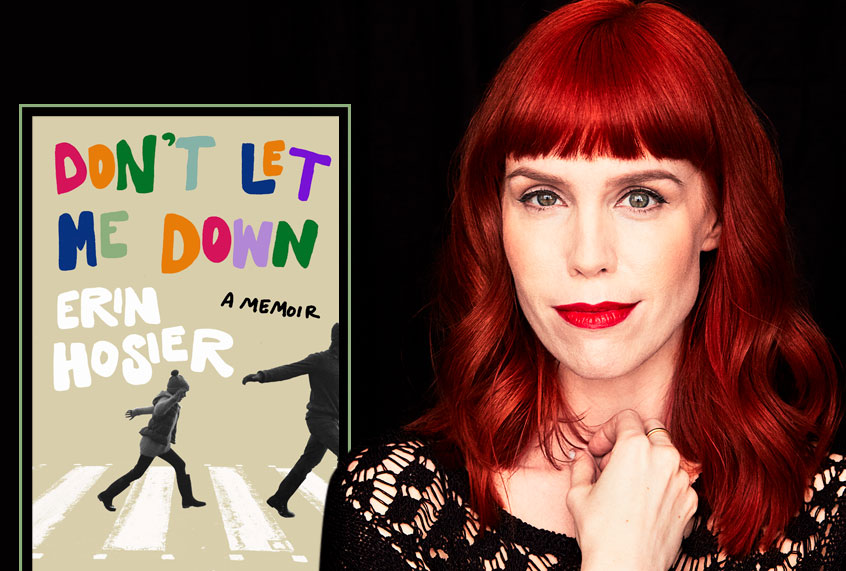

What would you do if I sang out of tune — would you stand up and walk out on me? When I stop and actually pay attention to the opening of this song I’ve heard my whole life, the vulnerability on display — the fear, rational or no, of a reaction so disproportionate to the error — is heartbreaking. The Beatles didn’t invent pairing a soaring melody and triumphant chorus with devastatingly sad verses, of course, but they did have a singular knack for voicing the otherwise unspeakable in our hearts. As does Erin Hosier in her incisive coming-of-age memoir “Don’t Let Me Down,” an account of growing up in rural Ohio in the ’80s and ’90s in a family shaped by her father’s dominant personality and rage, a sexually abusive neighbor, and the fear- and shame-based culture of conservative Christianity — all set to a Beatles soundtrack.

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

We often see the music of the Beatles used to convey a shorthand of innocence and nostalgia, but your memoir is not about that. I was curious if you were intentionally playing with, or even looking to subvert, those expectations that we might have for a book framed around a father-daughter relationship with this particular soundtrack?

I grew up with it. It was always on. And sometimes it would be like a happy, joyful mix of early ’60s, “Twist and Shout” stuff. Then it would be the White Album or even “Rubber Soul,” that has a number of songs that are really, really dark lyrically, but might sound otherwise poppy, like the song “Run for Your life,” which begins, “I’d rather see you dead little girl than to be with another man” and then goes on to describe like a textbook, “run for your life I’m going to kill you” [kind of narrative], which was something that was going on in my happy home behind closed doors.

It was a basic domestic violence, abusive relationship between my mom and my dad. My dad had a secret rage problem that only we could see, or the people that he was cutting off in traffic and screaming “F**k you bitch” at over a parking space on our way to church. Those mixed messages were always in the air and became really apparent to me because through the religious stuff I saw the parallels: growing up in an evangelical Christian household, where it’s all about God is a man, to these rock and roll records where it was like, God is a rock band. These patriarchal archetypes everywhere in my world. It just seemed like that’s been the theme of my life.

The relationship between rock and roll and patriarchal religion, or even once you move further out into the fringe, it’s such an interesting phenomenon to look back at now to see for people our parents’ age especially how much that rock star line was blurred for them, because they were a generation of seekers, right?

Yes, and rock and roll was the first music to subvert religion. Jerry Lee Lewis, when he played his piano that he learned how to play in church, as rock and roll — which is literally a metaphor for having sex, you’re rocking and rolling — it’s just those two things are so entwined. Even in college, I became a human sexuality major.

It was so weird. I was trying to go back and understand how all of these things could be so fraught with each other.

They are so intimately connected. I mean, “I’d rather see you dead little girl than see you with another man” and is this other side of the coin to “you need to submit wholly to your husband and let him guide the household.”

All of that stuff. It was your duty to be attractive. It was, whoa, getting up at 6:00 a.m. to make sure you could like get ready to be seen in 7th grade. I just saw that “Eighth Grade” movie —

I haven’t seen it yet. I need strength to see it.

It was just too painful. Because that little girl, I saw her on “The View,” that young actress, and she was like, “We teenagers should get more respect, we’re just people without rights or money.” I was just, “Oh my God, that’s exactly it.”

She must be protected at all costs.

I know. And that’s what the “Don’t Let Me Down” thing is: Religion, the nuclear family, and being white and privileged and middle class in America in a rural place in Ohio and you can still be a big failure.

No matter what, it’s going to let a girl down.

Something you said earlier, “basic domestic violence story,” really jumped out at me because this is a story about a lot of things including violence, domestic violence, father’s rage, corporal punishment, sexual violence. What struck me the most as I was reading this is how non-surprising all of that was to me. I think it’s a more common story than we like to acknowledge. Do you think violence as a part of the culture of suburban and small town America is under-examined or under-acknowledged?

To me it was absolutely normal. I never said anything when I was molested, at the time, to my family, and I knew that I would never say anything about it. It was only when my brave six-year-old brother spoke up about what had happened to him, which was clearly, extremely violent . . . I just forever blamed myself. Until a few years ago, when I told my mother that I had to write this scene, and that I knew that [the perpetrator] was capable of these things, technically. Even though I was 11 [when it happened].

All throughout my adolescence and whenever I talked to my peers about their experiences, they had that same “it was just inevitable” sad feeling about it. It was boys and girls, and it would always seem to come out during like, well we’ve taken LSD and I think I feel a little different, so I’m going to tell you about the time . . . . There were a bunch of scenes that I took out of the book because they were just, it was too many, it was so repetitious.

One of my best friends was raped in high school by someone who was even younger than she was, which was a big source of shame for her. He was 14 and she was 15 . . . she became pregnant from that and it was the first time she’d ever had intercourse. It was Ohio, and you still can’t get a legal abortion without parental permission, and wouldn’t you know it, she lived with her religious grandmother. We arranged for her to go before a judge and talk about her own rape, and raised the money. I mean we were doing this as kids, living out “SVU” episodes without any cops.

It’s one of the things that drives me. It’s shocking that people are shocked by the #MeToo movement.

The way people deny it, is just . . . it can’t go on because it’s too enabling.

The scene that you described in the book of with playground game, where the guys would [chase girls to grab their genitals].

“P**sy Patrol.”

When I read that, and I had not thought about this in years, but I remembered there was a similar game at my school, where boys would chase certain girls and then . . . there was not a specific protocol, but they would single out certain girls to do this with. It was happening on the playground in late elementary school. And nobody, teachers or anyone, paid any attention.

You feel thrown to the wolves. I didn’t learn what the word “neglect” really meant and that it was abusive until I was in therapy many years later. It sounds really blaming when you use that word to describe your own parents, but if you look at the facts of it, in our generation, so many of our parents were very, very young. Like my mother was 21, as a first-time mother she had no life experience whatsoever, and she was clinically depressed and had no idea that that was abnormal or that there was any help for that.

That’s why she turned to the church because it was a community of women who were also having horrible lonely experiences in their marriages and as homemakers. I don’t blame my mother who has done so much work on herself, but it’s like, yes, when you’re in bed all day or when you’re at the church function and you’re letting teenage boys do the babysitting, that was the ’80s, I guess. I think we have to be more vigilant.

I’m sure you’ve also noticed the ’90s are having a moment now, with us revisiting the media narratives, especially around women who were considered to be difficult or crazy or slutty or what have you, everyone from Monica Lewinsky to Lorena Bobbitt. Do you have any specific hangovers from that time that you work through as a woman?

Do you mean just the ’90s and the bullshit?

Yes! The ’90s and the bullshit.

It was such a confusing time because even before that, in the ’80s when I was a really little girl, like eight years old, I remember AIDS was happening, and they associated it with gay men and homosexuality. Oprah had her show where [people were] freaking out about somebody with AIDS was “licking the fruit” and it was just hysteria.

I remember thinking, if I’m a Christian, this is wrong? Maybe I’m gay because I’d had fantasies about kissing so-and-so at the slumber party or something, and if I’m gay, then I have AIDS, then so be it. I just didn’t buy it. I didn’t buy into homophobia even as a little person. When I was a teenager and in college when the Monica Lewinsky thing was happening, I was like, “This is outrageous.” I never struggled with it.

But the one thing that was interesting was that it was the time of Bikini Kill and all of my punk girlfriends were stripping. It was the Lusty Lady out in the Pacific Northwest, and it was the feminist stripper with — I don’t know, that was a confusing time, because I went and did my investigative work and went to a truck stop strip club outside of Ravenna, Ohio, outside Kent State and there were a couple of my friends going to go check it out, to do the sex work, and we would make so much money and pay for our school.

You get there and it’s a terrifying room with a pool table and not enough lighting and a bunch of scary truckers and some teenage girls in their underwear swaying listlessly to a bad childhood memory.

I didn’t buy it that the president wasn’t lying when he said, “I did not have sexual relations with that woman.” I was a college bartender when all that was going on. I couldn’t believe that the president of the United States was getting away with saying that a blow job wasn’t sexual activity, or something. I was always a little suspect of the Clintons.

It’s not much so different now. The R. Kelly thing . . . It was never hard to persuade me. It’s interesting to watch people struggle with having to believe that people are capable of the dark things that they are. I don’t know if you are reading about the Lady Gaga deposition in the Dr. Luke case? “What if your father was accused of sexual assault? . . . What if he didn’t do it?”

She’s like, but what if he did? Which would definitely be my answer. You have to accept that it’s possible that your loved one is capable of terrible things, or just really disappointing things. Where do you go from there?

Can we talk about the term “daddy issues”? Because I feel like that’s a term that gets thrown in a dismissive way towards women who’ve had complicated relationships with their fathers. There’s not really an opposite-gender equivalency, and it is never intended kindly.

Yes, exactly. It’s something that I had to Google all the time because I use it as a short hand to describe exactly what you’re saying. In the popular consciousness, it means women who date older men or wealthy men who they need because they’re calling them Daddy sexually, it’s a whole thing. To me, that’s not what it is. I’ve never been attracted to an older man. It’s more what I hear being projected on me by, like, terrible dudes that I went on internet dates with.

I’m now married, which is amazing because I didn’t think that it would ever happen to an actual healthy, normal human being. Even before the book was done, I was single and I was going on these bad dates and within the first 20 minutes I’d sit down with this douchebag at the usual bar and we’re 10 minutes into a beer and he’s like, “What do you do?”

“Well, I’m writing this book about my relationship with my father.” He’s like, “Don’t tell me you’re one of those girls who was sexually abused by her father.”

He just said that, “one of those girls.” I have heard that a lot. Somebody I just met once asked me if I was a “husband hunter” because I just said yes to a date. I don’t know what the f**k. All because I was in my 30s and I had the audacity to have never been married, or to be available that moment, but also have a job, so there must be something wrong with me.

I’ve seen and I’ve heard from friends who are still on the open market, that there are Tinder profiles that will say stuff like no sexual abuse, no baggage, no family bullshit.

That’s the equivalent of people who say “no drama” who are of course completely here for the drama. “No baggage”? Let’s examine yours.

Just really defensive, men usually. Just very nervous, I think. Part of the friend-zone weirdness.

I should research the provenance of “daddy issues,” where it came from and how it became such a catchphrase.

Remember “Loveline” in the ’90s?

My God, yes.

Dr. Drew. Some sad girl would call in and talk about her narcissistic boyfriend who was never going to leave his other girlfriend and blah, blah, blah —

“Where’s your father?” “How’s your relationship with your father?” They would talk about her voice. If she had too high of a voice, they’d say it was a baby voice. It felt like they were almost placing bets on whether the caller had been abused.

Oh my God, exactly. He would say, ”Where is dad?” My friends and I would be like, “Where’s dad?”

“Loveline!” This show was a mainstay in college. I didn’t know if everyone listened to it though.

It’s mostly Doctor Drew’s fault.

Seriously, the Dr. Phils, the Dr. Drews, these people with their soundbites about what makes women tick, it’s just disgusting. It’s comedic, except people really buy into it.

The sinister part of it I think is that they’re not saying “what issues did your dad have?” It’s a blaming thing: as a woman or as a girl, when you’re working through trauma related to your parents, that’s an issue you have. It’s your problem that you need to fix.

I feel there’s been a lot of a reticence to come around to the fact that physical trauma that you experienced as a child and emotional trauma, any abuse as a child, will affect you for the rest of your life. That is trauma, that’s PTSD. I feel like when it comes to women with PTSD, or who have extreme anxiety or deal with depression, it’s just like this: Oh, sad girl, poor little rich girl. She doesn’t have it so hard. This is no “A Child Called It.” I was hit when I was a kid. I turned out OK. I got married by the time I was 27 like a normal person.

I struggle with that, because I know a lot of people have it really bad. And I do feel like my father-daughter story was actually great in the sense that I did feel that he loved me. I feel like a lot of kids don’t get that and that’s really bad. At least it felt like him trying, and doing the best he could, and that he could connect sometimes on that level and that it was genuine.

I also feel like I could relate to the child of a psycho, or a con artist, or Brett Kavanaugh, somebody with deep-seated problems that there’s nothing I can do to help.

I would never be Ivanka Trump. I would never defend the indefensible.

Did you ever struggle with giving yourself permission to write this story?

Yes, totally. Especially for people in his family. In m family, I definitely had their support and permission, and they always trusted me to keep the focus on myself. Yes, I worry about his close friends and the people he worked with and just the many people who loved him, or members of my extended family who are still quite religious, things like that. So far people have been really supportive.

Yes, it’s definitely a terrible feeling, writing a memoir and having it published. I do not recommend it. I can’t believe that it’s happening.

It changed a lot about the way that I do business. When I work with other narrative nonfiction writers, or just writers in general who are thinking about memoir, write it first before trying to get it published maybe, because it took me so many years.

How long did it take you to write the book?

It was sold on proposal in 2011 and then a couple of things happened, like publishing nightmares with the imprint that’s folded into another one, then the editor comes and goes. It was a good five or six years of torment, back and forth, taking a break and writing and lots of things that ended up getting cut trying to shape the story.

As somebody who has now been on a couple of sides of the desk, as far as books go — as an agent and as an author and as someone who’s co-authored also — you’ve had a lot of different experiences. What do you think is the most important thing for someone who’s out there working on their memoir or working on an idea for a memoir right now for them to know?

I always say this, but just assume that you’re going to be paying to do it. Nobody is going to be able to give you enough money that is ever going to be worth it, even if it’s a lot of money, because it’s just not. You have to be willing to do it even if there’s no money. I would say to take breaks and try not to traumatize yourself, or re-traumatize yourself, just to meet a deadline.

Look at it as changing your life and changing your consciousness. It’s not just a creative project. It’s not just a job. It’s literally getting to the nuts and bolts of your life story and what it meant for you to be alive and what you want to pass on. No big whoop.

Right. [Laughs.]

Forgive yourself.

That’s very important.

No matter what. It just never feels good. Even if you’re getting it down and it’s really flowing, it’s just the fact that it’s even happening . . . I feel like I have to get permission from myself to keep going.