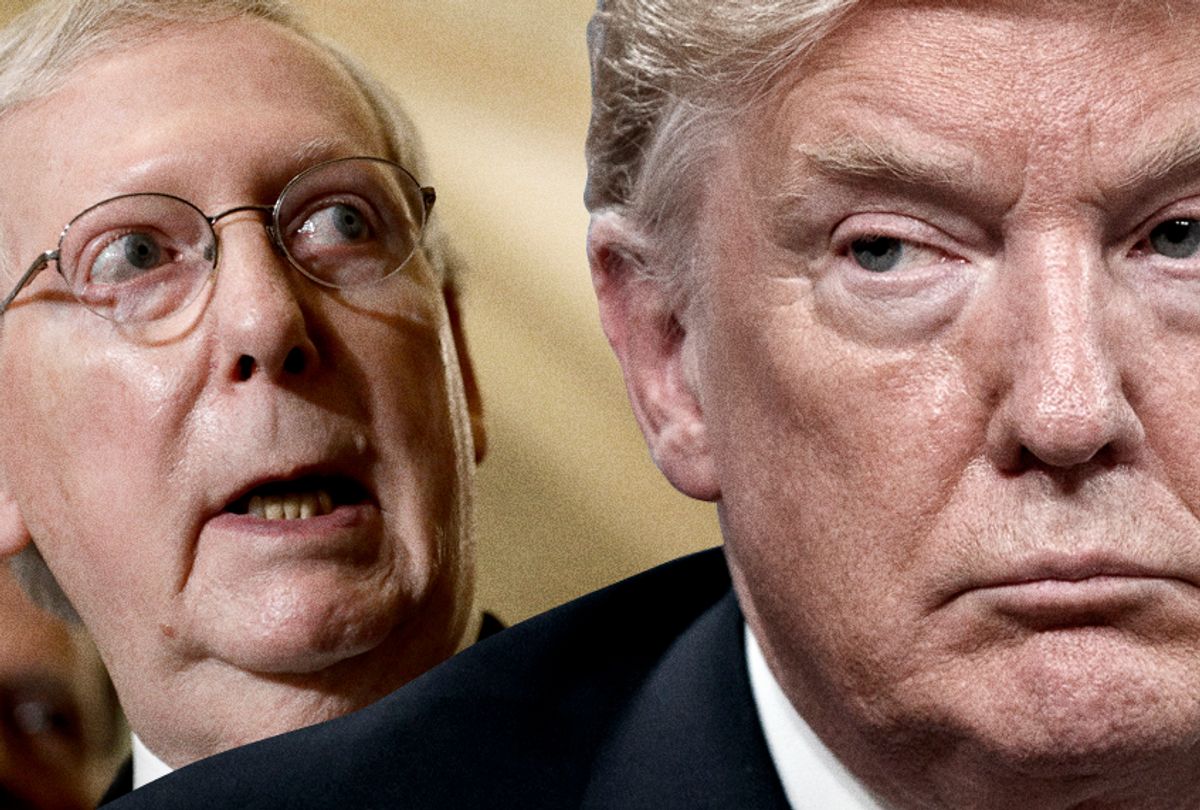

In his State of the Union address, Donald Trump gave Congress a choice between doing one half of its job or another.

“If there is going to be peace and legislation, there cannot be war and investigation. It just does not work that way,” he said. It’s a massive tangle of false claims, but the intended ultimatum was clear: Stop investigating me, or nothing will get done. The last shutdown could be only the beginning. “If you try to impeach me,” Trump threatened (in effect), “I'll impeach you!”

Of course he’s a blusterer and a BS merchant, but the threat was made nonetheless. And Trump can carry it out if Senate Republicans stick by him despite his weak hand, because theirs is weaker. Our Constitution allows for this, even if it doesn’t intend it and no one has ever contemplated it before.

Welcome to another episode of constitutional hardball, which I’ve described in the past as “things a judge might let you get away with under the Constitution, but that your mother never would.” They’re violations of norms, not laws, and there’s been growing discussion about them since Harvard Law professor Mark Tushnet coined the term in 2004.

Political commentators such as David Waldman, Matt Yglesias, Jonathan Bernstein and myself have long recognized constitutional hardball as something Republicans do more often and more intensely than Democrats — reflecting the well-documented phenomenon of asymmetric polarization, and the more systemic differences between the two parties described in "Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats," by Matt Grossmann and David Hopkins (Salon review here).

Only last year, law professors Joseph Fishkin and David Pozen brought that perspective into the legal world with a Columbia Law Review paper, “Asymmetric Constitutional Hardball,” which I wrote about here. While officeholders in both parties have engaged in the practice, “Constitutional hardball remains reciprocal but not symmetrical,” they argue. “One party, the Republican Party, has become especially identified with hardball tactics, with large consequences for our constitutional system.”

There have been at least two responses to Fishkin and Pozen's paper, and they’ve written a draft reply. The first came from David Bernstein of George Mason University and countered their examination of Republican hardball with his own list of Democratic examples — an approach that either ignored or denied their crucial symmetrical vs. reciprocal distinction.

The second response, by Jed Shugerman of Fordham, reacted to that confusion by advancing another concept: “constitutional beanball” — a term I’ve used myself in the past — to describe actions that are “fundamentally antidemocratic,” and thus distinctly different in kind. (For non-baseball fans: "Beanball" refers to a pitcher deliberately throwing the ball at a batter's head. It's an intimidation tactic, which is supposed to result in expulsion and fines.)

Shugerman writes:

The antidemocratic tactics of Trumpism are not a break from the establishment Republican Party, but rather are continuous, if only more extreme. The destructive politics of beanball reflect a deep existential paranoia, racial status anxiety, and a panic over dispossession and the loss of historical privilege.

“The paradigmatic kinds of beanball are the abuse of voter ID laws to give a structural advantage to your voters and to disadvantage the other side’s voters,” Shugerman told Salon. “I think another paradigmatic example is extreme gerrymandering, which both sides have engaged in, but the Republicans have pushed more aggressively and in many more places.”

There’s a bit of subtlety in his argument. “Some basic voter ID might be acceptable, or even reasonable,” Shugerman said, “but the rules that Republicans have adopted in places like Tennessee and Texas — enabling voter ID for gun permits but not for student IDs — are obvious bad faith structural rigging" -- in other words, constitutional beanball.

There are other sorts of examples he points to as well. “Manipulations of the Department of Justice are a kind of beanball -- using the system of prosecution to reward your political allies and to punish your opponents,” he said. “This is another example of the continuity from the pre-Trump era. The George W. Bush manipulations and partisan abuses of the DOJ have a direct through-line to the Trump abuses of the DOJ. Nothing Obama did with his Justice Department comes close.”

Another paradigmatic example is “racial marginalizing and stigmatizing the other,” he said, citing the birther conspiracy theory as a high-profile example.

“We think Shugerman’s core point is powerful and correct,” Fishkin and Pozen write in their response, but they have reservations. First, they note:

We are skeptical that the hardball/beanball distinction can be demarcated with a bright line. While Shugerman seems to suggest that hardball and beanball are distinct phenomena, it seems to us that beanball is better understood as a subset of hardball.

In an email to Pozen, I questioned the need for a “bright line": A good deal of intellectual life is devoted to negotiating conceptual boundary disputes, and a subset can still be a distinct category (as mammals are a category of animals, for example). Pozen was generally sympathetic:

I agree that there does not need to be a bright line. The question, as I see it, is whether the introduction of a new conceptual category such as this one (beanball) gives us new analytic purchase on the phenomenon of interest (hardball). For that to be possible, the boundaries of the new category must be at least reasonably well defined, but they need not be and often cannot be perfectly precise.

One way of understanding the relationship, I suggested, is that all constitutional beanball is hardball, but not all hardball is beanball. This helps illuminate the often, but not always harmful nature of hardball. Pozen replied:

On Shugerman's account, it seems that beanball is always harmful because baked into his definition is the proposition that beanball is "fundamentally antidemocratic." But of course, this just shifts the inquiry to what counts as a fundamentally antidemocratic practice. Shugerman does not really take up that inquiry in any sustained way -- which is only natural in a short response piece.

Shugerman does, however, raise an important point about the normative heterogeneity that exists within the world of constitutional hardball. I am not sure that we need the term "beanball" or that it's the most felicitous metaphor, but if people find it a useful heuristic for that point, so much the better.

Shugerman’s motivation in coining the term, he told me, was two-fold:

The debate breaks down when everything is treated along the same axis. When everything has the same category of hardball, you have Democrats cite their grievances, and their examples of aggressive tactics by Republicans that they object to, and then Republicans respond in kind. It seemed to me obvious that these categories just blend together and obscure more than they reveal, because everything can be categorized in the same bin.

There seemed to be something going on that was “categorically different from legitimate hardball tactics,” he said, which is where being a sports fan came in handy. “I understand that hardball in baseball is a legitimate and appreciated style of play, whereas beanball is a kind of tactic that gets you rejected and fined.”

Even if there weren’t sharp lines in constitutional law, couldn’t we use unambiguous cases to help elucidate what’s going on, I wondered? We could pursue two distinct lines of inquiry: into core unambiguous cases and into contested ones, placing both in a comparative framework.

“One way to refine our normative intuitions about which types of hardball are most worrisome," Pozen replied, "might be to work our way outward, inductively, from ‘core’ cases that are widely understood to be fundamentally antidemocratic.”

One reason things may have been muddled until now is that most of the high-visibility drama has been around matters that Fishkin, Pozen and Shugerman all agree are hardball, not beanball.

“Most of the congressional hardball we’re interested in having to do with supermajorities, senatorial conventions and courtesies, filibusters, etc., is all just ordinary hardball, not beanball," Fishkin said. "It’s not disenfranchising anybody. Partisan gerrymandering might be harder to categorize – although no voters are losing the right to vote, the way vote dilution erodes effective representation is deeply damaging to democracy.”

In his response, Shugerman similarly wrote:

Most judicial confirmation battles have been escalating hardball, not beanball. Republicans blocking [Merrick] Garland was hardball, and yet not beanball. The Republicans in the Senate legitimately had the votes to block Garland, and they chose an aggressive norm-busting tactic to maximize their chances to prevent any defections. It was unprecedented, but it was not fundamentally anti-democratic to use their votes to postpone an appointment.

But he did say “most judicial confirmation battles,” and there’s a good reason for that: the case of Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation, when the Trump White House and Senate Republicans sharply limited access to Kavanaugh’s records and answers to troubling questions about his professional career, even before they limited the investigation into multiple allegations of sexual misconduct. As Shugerman explained:

While it is common for political actors to play hardball with access to information and investigations, a nomination to a lifetime seat on the Supreme Court is a special case, because the Supreme Court itself is a special case in a democracy because of the countermajoritarian difficulty and the escalating role of judicial review and judicial supremacy. Confirmation hearings are the only chance to vet a nominee for an office that will shape American democracy for decades. Blocking valid investigations may be hardball in other contexts, but it was beanball in this context.

In the course of our conversation, however, Shugerman shifted a bit. He had already highlighted the fact that bad-faith arguments can play a crucial role in marking actions as beanball, and he noted that in order to block Merrick Garland’s nomination, “Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell falsely claimed that presidents have not appointed Supreme Court justices in presidential election years.”

When I asked Shugerman whether bad-faith argument might be considered as a factor further structuring his analysis — distinguishing between blocking Merrick Garland and confirming Neil Gorsuch, for example. he said that was possible.

“You have another category of hardball which is bad faith hardball,” Shugerman noted, he said, in contrast to the one he calls "transparent hardball." The Gorsuch confirmation was an example of “good-faith hardball, where Republicans "decided to get rid of the filibuster because they want to get him through, but everyone sees it happening, and it's not being constructed by a lie,” Shugerman said. “Then you can have the blocking of Garland, which is bad-faith hardball. And then you have the Kavanaugh confirmation, which is bad-faith beanball.”

All this might seem like pointless nitpicking, given that it doesn’t change anything about who’s on the Supreme Court. But clear thinking is a vital component in any long-term struggle, along with passion, organizing skill and many other things. Such clarity thinking is urgently necessary in making sense of where we are now, how we got here, and how we can get out.

Part of this involves expanding our horizons. “I think the next step is to look more historically, and to try to identify beanball of the past,” Shugerman said. Although Fishkin and Pozen's analysis was limited to the post-Cold War era, Shugerman pointed out that they reference Richard Hofstadter’s famous essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” which he called “an interesting hint that probably we should be looking back further to the origins.”

Hofstadter helps explain the motivation towards hardball with the observation that if “what is at stake is always a conflict between absolute good and absolute evil, what is necessary is not compromise but the will to fight things out to a finish.” That’s a motivation for beanball as well.

“First, I'm interested in looking at more continuities back to American politics from McCarthy to Nixon to Trump, and the continuities of Republican Party beanball,” Shugerman said. “But I'm also interested in thinking about beanball dating further back -- to the founding. To what extent were the founders engaging in hardball, or even beanball? In the run-up to the Civil War you see a lot of beanball.”

These tactics come easier to the GOP because of its more ideological nature, shading into absolutism. Fighting back against them is more difficult for a diverse coalition more focused on practical problems of everyday life — health care, education, jobs, a healthy environment.

We have found ways to do that in the past, and we can do it again. We can see that in how the Resistance has informed the House Democrats' first legislative agenda, the far-reaching democracy reforms in HR 1. The threat to democracy is existential and can no longer be ignored. Which is why Stacey Abrams’ State of the Union response was such a fitting answer to the threat posed by Trump.

“Let’s be clear: voter suppression is real,” Abrams said. “From making it harder to register and stay on the rolls to moving and closing polling places to rejecting lawful ballots, we can no longer ignore these threats to democracy.”

Seeing those threats through the lens of constitutional beanball -- unfair and unethical tactics that all those who value democracy should reject -- empowers us to see the true magnitude of the struggle we’re in.

Shares