Affordable health care providing universal access has long been a holy grail of the Democratic Party. Like the grail itself, however, many have tried to obtain it, and all have failed in the efforts.

Even after the implementation of President Obama’s Affordable Care Act, American health care is still neither particularly affordable (especially after repeated Republican efforts under the Trump administration to gut its main elements), nor is the access universal. Unlike in most other countries, U.S. health care is still largely predicated on employment, despite the insistence of many that it is a “universal right.”

On the other hand, a wholesale restructuring of the existing employee-based patchwork system with a single-payer Medicare for All system seems to be equally challenging without a huge Democratic majority in Congress and a sane operator in the White House. Despite growing political support (helped by an apparent endorsement by former President Obama), it is still not a goal universally shared by Democrats in the present congressional term, if recent statements by Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi are anything to go by. A tough row to hoe.

While we wait and perhaps agitate for a better health care system, it’s worth examining other potential remedies that can improve what we currently have coming from a different political logic that the current political alignment may find even slightly palatable. Consider, for example, that the Trump administration has some kinds of price regulations in mind with regard to pharmaceutical prices, regulating them against what they cost on average in other countries. “Lower costs” and “administrative simplicity” have currency in this political climate. If Medicare for All remains a bridge too far, what about the concept of the “all-payer system”?

In general terms, as Sarah Kliff, a leading health care journalist, has highlighted, an all-payer system means that all payers pay the same price for the same procedure or drug everywhere, so issues such as the asymmetry of bargaining power (which exists in the current system, say, between a consumer and a health insurance conglomerate or HMO) cease to matter.

Of course, $1 means different things to people of different economic levels. But the variance in price for the same medical services is gigantic, and the power of fixed prices would steamroll many of the worst elements of the system we currently have in place. Consider that the taxi businesses in many cities profitably operate on fixed rates, as do health care systems in other countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

How would it work? As the economist Uwe Reinhardt puts it: “All private and public insurance programs in a region would pay all physicians, hospitals, and other providers of health care on the basis of a uniform fee schedule common to all payers, and the cost of uncompensated care rendered to uninsured patients would be covered by a separate fund.” In essence, the goal is to ensure that everybody pays the exact same price and the same rate for any procedure or medicine, regardless of where you live or work. And everybody is covered.

Decades of “reform” in this country have demonstrated conclusively that simply tinkering with the existing system won’t work. America’s health care provision delivers inferior outcomes relative to those in other countries, which do provide universal health care coverage. And for a country that supposedly has the most market-savvy consumers in the world, U.S. health care furnishes remarkably lousy value for money for them, as the OECD’s “Health Care at a Glance 2011” highlighted:

“The same set of hospital interventions (including the normal delivery of a baby, a Caesarean section, a hip or knee replacement, etc.) cost 60 percent more in the United States than in a selection of other countries. Similarly, 50 high-selling pharmaceuticals cost 60 percent more in the United States than in Europe. …Overall, therefore, high prices are the main reason for high health care spending in the United States.”

Prices remain so high because the overall system (outside of Medicare) remains largely administered via a for-profit private health insurance oligopoly, and pharmaceutical companies, which preserve margins via predatory price gouging, and literally kill people in the process because of lack of affordability.

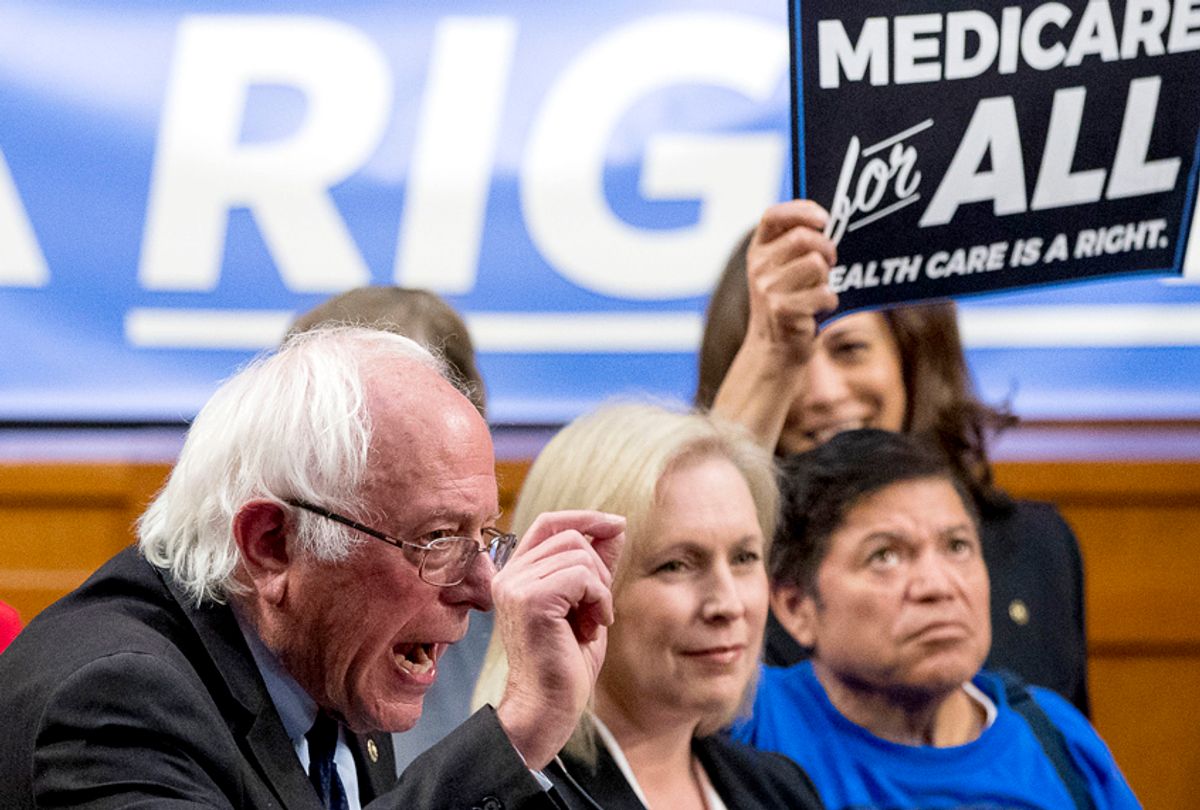

As a result of these longstanding failures, “single-payer” proposals such as Medicare for All have finally started to gain serious policy traction, especially within the progressive wing of the Democratic Party. Single-payer can take many forms, but in essence, it is a system in which a single public or quasi-public agency provides health care financing (via taxation or social insurance charges). But even though publicly funded, the delivery of that care remains in private hands. This is fundamentally what Medicare is, and the goal of politicians such as Senator Bernie Sanders is to expand Medicare provision to all Americans — Medicare for All.

In health care, the right is ideologically fixated on the idea that the answer to predatory pricing is more competition (which can’t work in imperfect medical markets, for reasons highlighted by economist Paul Krugman). By contrast, a large number of elected Democrats, both at the federal and state levels, want to do it through single payer, which has worked in other countries where the insurance and pharmaceutical industries don’t represent 15 percent of GDP.

Unfortunately, the fact that Big Pharma and a large private health insurance oligopoly exist in the United States is precisely what makes Medicare for All tricky to enact. With each reform threat, the two groups — Big Pharma and the health insurance industry — quickly mobilize opposition in Congress (to whom they have generously donated precisely for this purpose), much as Wall Street banks thwarted wholesale financial reform in the wake of the 2008 crisis, even when those banks were at death’s door.

All-payer systems have many of the same virtues of Medicare for All, particularly the reduction of costs and minimal overhead and complexity. The key feature with all-payer systems is that everybody pays the same government-set price for the same drug or procedure, which keeps costs low (as do single-payer systems). But as Kliff notes, the key distinction from the Medicare for All proposal (or other forms of single-payer) is that “Single payer does this by eliminating private plans for one government plan. All-payer rate setting gets there by setting one price that every health insurer pays for any given medical procedure.” But in banding together, a country’s insurers can achieve cost savings comparable to nations where single-payer is operative, argues Kliff, who cites the international pricing data to illustrate the magnitude of the price differentials currently existing between the United States and these other countries.

The virtue of the all-payer system in contrast to single-payer is that the former allows for the existence of multiple insurers — government, private commercial, nonprofit — thereby avoiding the politically toxic threat (largely exploited by the right) of a big socialistic government, via rationing and “death panels,” taking full control of your existing health care, and destroying it in the process.

States such as Maryland already use this kind of system when they negotiate with hospitals, and several European health systems, such as Germany and Switzerland, have, as Kliff illustrates, “long used an all-payer approach on a regional basis for physicians, hospitals, pharmaceutical products, and various other providers of health care.” So has Japan, an aging society that arguably has an even more acute demographic problem than the United States. Kliff cites a study of that country’s all-payer rate setting program, published in Health Affairs in 2011, which found that “the share of the country’s economy devoted to health care grew 0.8 percentage points between 2000 and 2008. During the same time period, American health care grew 2.7 percentage points.”

The “all-payer” system, then, cuts less against the grain of the existing American health care architecture. The government does not eliminate the private health insurers but merely sets the standard prices that providers can charge. In countries where it currently exists, negotiated rates are established over a medium-term time frame, usually two to three years, by an independent rate commission with representatives of providers and payers. And because of the existence of a uniformly imposed fee schedule, the cost of, say, an appendectomy, or a cancer treatment, remains the same, regardless of one’s insurer, the hospital, or the state in which one lives, so administrative burdens are significantly reduced, as is the cumbersome complexity of our current health care system.

Of course, the stringent cost controls built into all-payer are exactly why the for-profit insurers and pharmaceutical companies will still vigorously oppose its introduction. Both industries thrive on complexity and minimal efforts to contain spiraling costs, which fatten their considerable margins. Their usual justification for these exorbitant profit margins, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry, is that intense price controls stifle innovation. But some of the most innovative developments in health care treatments have arisen in countries that tightly constrain costs, such as France or Switzerland (which also have thriving pharmaceutical sectors). And as the Commonwealth Fund has illustrated, the lack of price controls hasn’t exactly given the United States a massive qualitative edge in health care provision:

“1. The U.S. ranked last place among the 11 countries for health outcomes, equity and quality, despite having the highest per capita health earnings.

2. The U.S. also had the highest rate of mortality amenable to healthcare, meaning more Americans die from poor care quality than any other country involved in the study.

3. Poor access to primary care in the U.S. has contributed to inadequate chronic disease prevention and management, delayed diagnoses and safety concerns, among other issues.”

It is also worth noting that like many of their counterparts in other industries, U.S. pharmaceutical companies in particular are increasingly deploying their substantial profits not toward R&D, but share buybacks, which also undermines the justification for the exorbitant prices of their products. Big Pharma’s other rationale for high prices — namely, to recoup the amount of time and cost deployed toward the research undertaken — also conveniently ignores the fact that many of their “pioneer” drugs were originally devised in academic laboratories with considerable federal government support, only then to be patented and licensed to private companies, as former Congressman Henry Waxman notes in a 2017 report, “Getting to the Root of High Prescription Drug Prices: Drivers and Potential Solutions.”

To get around the likely opposition to all-payer in the United States, Uwe Reinhardt has suggested taxing prices that vary too much from the Medicare or Medicaid reference prices, as opposed to banning private health insurance altogether, as California Senator (and presidential candidate) Kamala Harris recently suggested (and subsequently walked back). Regulators can just extend the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services fee schedules to the private sector. After a few rich specialists retire, and the hollowness of the claims of Big Pharma are exposed, we can settle down to a new normal of non-predatory pricing as occurs in the rest of the OECD. Only if for political reasons we discover we can’t have direct all-payer regulation of medical prices (which most advanced countries no matter their insurance systems have) might there be a need to resort to Plan B, namely, a single-payer system in which government or large organizations use their monopsony power to set prices.

To the complaint that even all-payer introduces a huge new level of “statist” government control antithetical to the “values” of America’s market economy, it is worth noting that it is only “statist” in the sense that electric utility rate commissions are statist. But it doesn’t require “socializing” anything, any more than utility regulations do.

The optics of health care are changing. Given the hard political realities of the United States, what is most likely to happen in the next 10 years?

Shares