“Mommy, I don’t like my body.”

I live in fear of the day that I hear those words spilling from the lips of one of my young daughters. When they begin to realize that society often cares more about what they look like instead of what they do, how they appear rather than who they are.

That day may come sooner than I anticipate, too, because research shows that kids — not just teens, not just the stereotypical college students or middle-aged women — are developing eating disorders at rising rates. Children as young as seven years old have been diagnosed with eating disorders, and treatment centers have begun to introduce specific programs catering to these young patients.

It cannot be ignored that children and adolescents worry about their weight. They obsess about their bodies and whether they are “too big” or “too small.” They try to avoid the all-too-natural and normal onset of puberty. They worry about fitting in and compare themselves to their classmates.

They develop anorexia. Bulimia. Binge eating disorder. Alternately, they may hover on the edge of a diagnosable disorder, with behaviors that don’t quite fit the medical criteria but still affect their quality of life. That still don’t let them accept and embrace who they are and what an asset they can be to the world.

For me, my fear of my daughters developing an eating disorder hits closer to home. Eating disorders are hereditable, and children with a relative who suffered are 7-12 times more likely to get one themselves. I struggled with anorexia for twelve years, so my girls are at risk. They are vulnerable. And in this world, with its constant pressures for perfection, that fact is frightening.

This is one of the reasons why I can’t simply sit back and “see what happens.” Why, like many parents, I make a daily effort to strengthen my daughters’ self-esteem. Why we focus on their strength and their kindness and their generosity. Why we play sports and sing songs and read books. Why, when we play princess, we talk about what else is there, beneath the crown and the sparkles.

This is why I write, too.

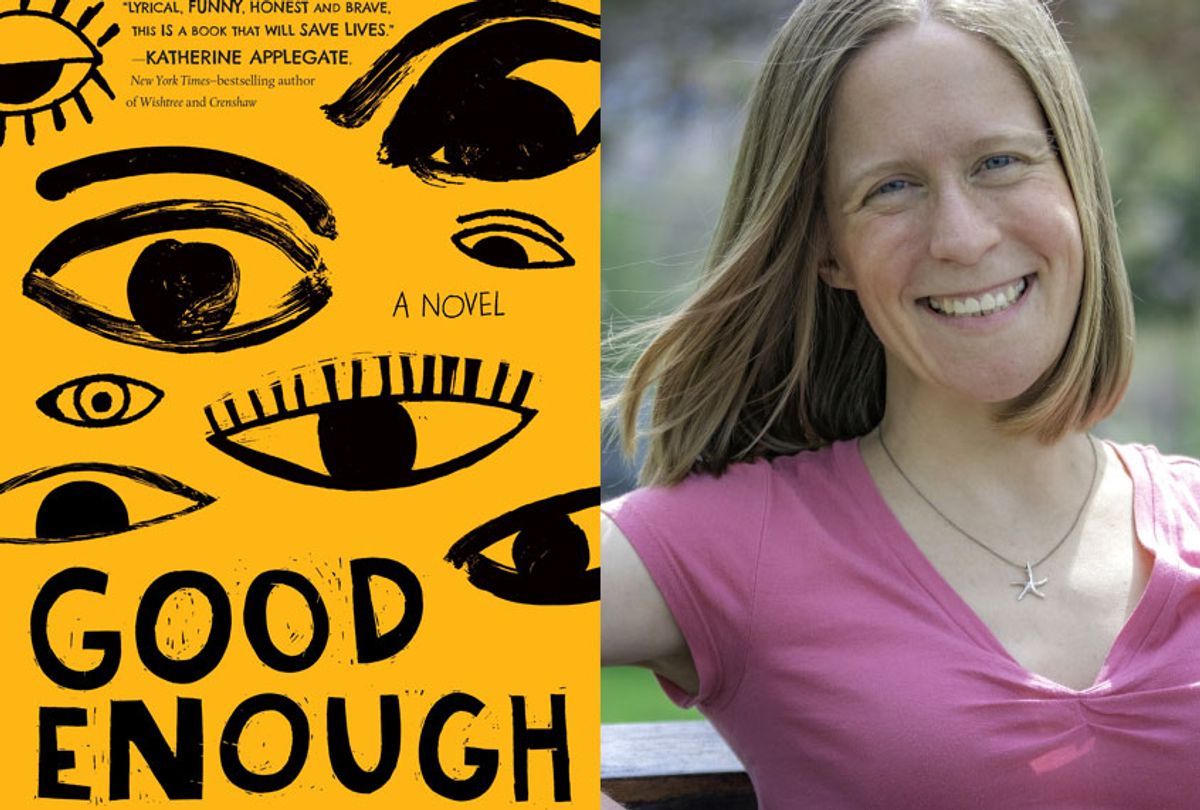

I also write so that that those who are lucky enough to be untouched by this illness can begin to understand what their peers and family members could be going through. In my middle grade novel "Good Enough," twelve-year-old Riley has just been diagnosed with an eating disorder. She’s been checked into the hospital by her parents, who don’t understand the way her mind works and why getting better is so hard.

When I was sick, I felt like no one understood me either. They didn’t understand how hard it was to follow through on the actions that I knew would aid in my recovery. I said I wanted to get better but still skipped meals. I claimed to want to gain weight but couldn’t stop myself from exercising. My friends and family tried to understand, but they could never quite grasp why my brain continued to sabotage itself. There was always a barrier between us, a hazy curtain they had to squint through to see me more clearly.

There was always a language barrier.

"Good Enough" and its companion nonfiction guide to recovery, "You Are Enough," are my attempts to break that language gap. In "Good Enough," I get inside Riley’s head as she heals. I translate the way eating disorder sufferers think so that their loved ones will be able to understand them and help them more.

My books are also a way to speak, in their own language, to the ever-increasing number of kids out there with an eating disorder so that they can finally feel seen and understood. In the scenes I paint and the characters I create, as well as through the exercises and interviews I share, I hope these readers will come to understand that their minds aren’t irrevocably broken and that they can get better.

Too many people in the world today believe that they are broken because of the circumstances of their lives. We all acknowledge that adults go through hard times, but it’s much harder for us to admit that kids do, too. It’s harder for us to admit that there is sometimes darkness dimming the light of childhood.

That’s why I write about these tough issues for kids. Why I share what I’ve been through and how I got through it. Because these situations are already in the lives of our children. There’s no use sheltering kids to preserve their innocence when the better option is to be honest and offer hope. When, instead, we can shine a light for those who need it.

We can let them know that recovery from an eating disorder is possible.

We can assure them that even in the society we live in, the one fixated on “superfoods” and “ideal weights,” on achievement and school rankings . . . even in that society, it is possible to find peace within yourself.

Eating disorders can affect kids and adults. They can affect those who identify as male, female, or are nonbinary. They can take over the lives of those who are LGBTQIA+ or those who struggle with chronic illnesses. They can hurt those of any shape or size.

Anyone can develop an eating disorder. But anyone can recover, too.

Truly. After more than a decade of struggle, I am proof of that.

This is why we need these words of hope. This why authors share these messages of redemption through fiction.

Our readers need our support and our acknowledgment that their journeys are valid.

Because I dream of a world where my children — where all of us — don’t think about our bodies anymore. I look forward to the time when all sizes are valued and food is delicious fuel.

One day.

One day soon.

Shares