Mushing is all over social media these days, giving fans from less frozen climes a front-row seat to the joys and tribulations of working with happy dogs through hostile weather in this extreme endurance sport. But when Kristin Knight Pace's first marriage broke up in 2009, and she packed her two dogs Maximus and Moose to a house-sitting gig outside Denali National Park for the winter and take care of a friend's sled dogs, there were no hashtags to follow to loop vicariously into the tight-knit community of elite dog sled racers in Alaska and beyond, just old-fashioned reliance on neighbors to survive her first winter and figure out how to build a new life.

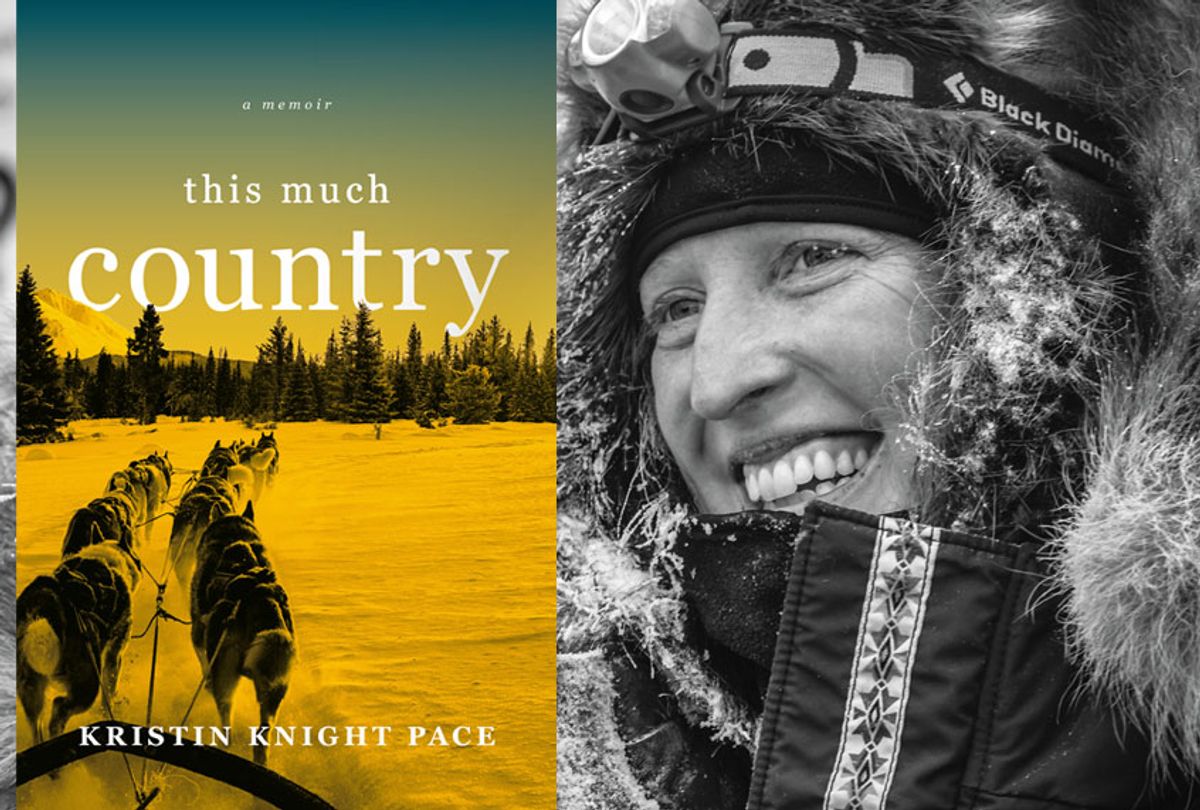

Moving away is a time-tested method of dealing with heartbreak, but as soon as Pace arrived in Alaska she faced more immediate problems: hauling water, splitting wood, taking care of the dogs and herself in temperatures that routinely dipped to 30 and 40 degrees below zero. In her new memoir, "This Much Country," she writes movingly and candidly about the challenges she faced, and in so doing developed a renewed faith in her ability to take care of herself, no matter how daunting the circumstances.

First working as a dog handler for legendary mushing champion Jeff King, she built a sledding dream team and, with her now-husband Andy, a breeding and training operation of their own, Hey Moose! Kennel, named after her beloved big dog she brought with her on that first move to Alaska. Pace's beloved sled dogs — Solo, Kabob, Littlehead and the rest of the pack— are the not-so-secret stars of her memoir, too; their individual personalities and boundless energy and drive make the Alaskan wilderness landscape of Pace's world feel as populated as a crowded city block.

Pace and I spoke last week by phone about mushing in the age of social media, what living in remote Alaska taught her about politics, and how climate change is affecting an entire way of life in the north.

A few years ago I knew next to nothing about the world of dogsled racing. Maybe once a year, the Iditarod start would be on TV. Now because of social media, mushers and kennels and their dogs have become more accessible and high profile. Has any of that affected you?

Yes. It's been a game changer. Most of us are out here living these pretty remote lives. For example, currently my cabin does not have road access right now because our road turns into a trail in the winter. I'm out here and I'm not even able to drive to my cabin. I have to haul water in here, haul propane in here so I can cook food, but I still have Wi-Fi so that's how we stay in touch with the rest of the world. We have a website, Facebook, Instagram, we have a ton of fans.

It is definitely good and bad, probably like anything other thing with social media. People get to feel a much bigger connection with us and the dogs, but also we're all pretty shy of the spotlight. You know, with mushers, we would prefer to be out here in quiet places with our dogs and not really having to respond to fans every day and all that kind of stuff, you know? It's amazing because our dogs get sponsored by fans and people come out to the races and they cheer us on and their support means everything to us, but it's definitely a balance.

Are your dogs influencers now? Are you thinking like, "this is how we should photograph this one" or "that would not be on brand for this particular dog"?

[Laughs.] Littlehead, who you read about in the book . . . when we first started our kennel I was dreaming of someday running the Iditarod, and so I made up a little list that said "Dream Team" and it had the 16-dog team I would take on the Iditarod Trail one day. And then Andy drew a picture of a basketball jersey with the number 23 for Michael Jordan, and he wrote "Littlehead" on it. It made me laugh so hard. That's what we made our hoodies into — we have our Hey Moose! kennel hoodies and on the back it says, "Littlehead 23."

Oh my gosh.

She is totally an influencer.

Littlehead sounds like she would be really into that part of the job.

Oh, totally. She is ridiculous. I love her so much. She's sitting out there in the sun right now with a leg bone of some sort that she must have found in the creek and just kind of lording it over all the other dogs.

One thing that I really appreciated as a reader was how evocatively you write about the dogs. After we get to know Maximus and Moose, and once the sled dogs start multiplying, there are a lot of them but they all get to have this unique spirit on the page, the way that any character would. As a person with a dog, I started thinking about how difficult it must be as a writer to articulate that because so much of our relationships with our dogs are both physical and also interior-driven, if that makes sense.

Oh, it's so true. 80 percent of our relationship with them is body language and looks between each other and tone of voice. That is a really hard thing to translate onto a page. It's also a really hard thing to translate to people who don't have dogs or who don't have the same relationship with dogs as we do.

I made the mistake of seeing that there were customer reviews of my book on Amazon and I'm like, "Oh, wow." Most of them have been great — and I decided to stop reading them, obviously, because you just shouldn't do that — but one of them was kind of making fun of me for the dogs having a voice and talking sometimes.

What?

For someone who doesn't live as amongst these dogs as though they, they are our family, they are the people in our life. For someone who hasn't experienced that I can totally see how that would be really weird and yeah, it's difficult to translate that relationship to the page. I definitely tried.

I thought it worked really well. You did do a pretty light touch, I have to say, with the voices. That goes a long way.

My editor was like, "We need more of this." Because I only had it in there once, I think. She was like, "This is so funny. This is hilarious." She is a dog person too. I'm just so overwhelmingly happy with every part of it because this book is me. It could not be more me. We talk to our dogs and they just talk to us. That's what it is.

Your book paints such a vivid picture of how different life is in remote parts of rural Alaska, which you were describing in the beginning of our conversation. It's different even from rural parts in the lower 48. The rural-urban divide is one of those major division points between Americans these days. What do you wish people who live in or around cities, or even just closer to running municipal water, understood better about the reality of remote rural life?

This is something I wish I could bring to the urban world, the citified world, or lower 48 in general, I guess, is there is a little cluster of us back here and we all have to rely on each other and help each other. We ski over to each other's houses with milk or sugar if you forget something. We just got a grocery store this year, so for the last seven years of us living here if you forgot something at the store in Fairbanks two hours away, you just were kind of stuck without it. We have pulled each other out of ditches, we have plowed each other's driveways, shoveled each other out. We have this pretty intimate bond with all of our neighbors, but we all don't agree politically on everything.

Alaska is known for fierce independence and no one sits inside a box. I have these neighbors who are gun toting, card-carrying members of the NRA who smoke a bunch of weed and believe in essential oils and they have crystals all over the house hanging up right next to the [taxidermied] sheep heads.

It's such an incredible community and no one fits inside a box of any kind of political stereotype. We all accept each other for who we are and we don't judge each other for disagreeing politically. We also have to help each other. I think that's something that I just wish I could see, and there is so much division in the country now that it's really hard to even read the news.

When you take away all of that and you strip it down to this very difficult tough life where we live, it makes all of that manufactured divisiveness melt away. It's kind of a magical thing to see that communities really can work together even if they don't agree on everything.

There was one part in the book where leading into a scene you mentioned that you were writing an article about climate change and how it was affecting the big dog sled races.

How is climate change affecting Alaska, and I guess secondarily, the dogsled racing culture that you're part of?

It's on a huge scale. From races being rerouted due to lack of snow to thin river ice to sea ice being completely gone. You know the Iditarod goes across Norton Sound, it goes right across the ocean right there. That's the race trail and this year they are going to be sticking to the shore line because the sea ice is gone.

I ran Quest in 2015 and the Iditarod in 2016 and we just went right across the ice.

That's an incredibly fast rate of change.

It's crazy. But do you know the craziest part is? For us, we are on the trail for two weeks and we have these crazy experiences, but it is ephemeral, you know, it's gone after those two weeks. But for the people live out there on the trail in those villages? Oh my gosh, the effects of what is happening to the climate is changing their entire way of life.

For the mushers it's like an inconvenience or a scary moment or for me, a scary several hundred miles of mushing on the dirt, but for them it is like falling into the river with the snowmachine and drowning on the way to see their grandparents, or the rivers that are the highways for them in winter between villages to have communities, to transport goods. Those are melting away and it's just heartbreaking to see history literally melting with the ice and see this way of life having to change so swiftly.

That way of life has been around for thousands and thousands of years. These people living a subsistence lifestyle in the villages. People need to take it seriously that this is disappearing for them. People should just go up and see it, it's really crazy. Some of these villages are right on the coast and they are eroding away and having to relocate the entire town. It's really, really hard to see. The reality of it is undeniable up here.

Is that one of those points that everyone can pretty much agree on or are there political differences over the realities of climate change and what should be done about it?

You know, it's really hard to go up there and pretend like it's not happening. I know that Sen. Murkowski, who seems like a pretty levelheaded lady, spends a lot of time up there and is a witness to it, is actively bearing witness to it. Yes, she's a Republican and I know that climate change issues don't necessarily resound with that base, but in true Alaska fashion she seems to fearlessly advocate for the real-life people living here. That's a really nice thing to see. I do feel like they are being heard here, but I don't think that the people of rural Alaska are being heard on a national stage as much as they probably hope to be, and as much as they deserve to be, because they are being so heavily impacted by this.

That's troubling. Let's switch gears into the big racing chapters. There are some passages in the book that were both inspiring and kind of infuriating, when strangers would make comments about the fact that you are woman and you are going out on these two major races. Despite, as you write about, Susan Butcher being such an Iditarod trailblazer in the '80s, for God sake. Is dogsled racing still seen as a male dominated sport still or were those out-of-left-field one-off comments?

I was just talking about this with my husband last night. We, the mushers, never talk about it as being a male dominated sport. I have never heard anyone say that except for fans or reporters or other people asking me questions about it.

Women have been running the Iditarod for a long time and the Quest too. It's just a normal thing to have women running. Some years there is a ton of women running and some years there is only a handful, but it's definitely not a male dominated sport. Right now the Junior Iditarod just finished up and [six] of the competitors were girls, [ages] 14-17.

Why are girls and women so drawn to and so successful in this sport, do you think?

I don't know. When I worked at the National Park kennels people would always say, "Why is it all women working here?" My boss Karen would just be like, "I just hire the most qualified people who are super passionate about these animals and want to work with dogs and it happens to be all women." I don't know if that's part of it. I feel like all of my male mushing friends have just as deep a connection to their dogs as I do. I just think of the door's open for it. No one is going to give you a weird look if you are a girl dog musher in Alaska.

Unless you are a reporter coming up from somewhere, and then for some reason it's a surprise.

Then maybe it is an unusual thing, but it isn't up here. I had just done an interview yesterday where I was telling them that . . . we don't look at how anything is traditionally seen. We just do it. That's just the ethos up here, I feel like. Plus traditionally, you're not seen at all. You're in the middle of nowhere up here. There is no one there to judge you for anything you want to do, so we just do the thing that makes us happy.

So now that you're a parent do you get the, "But you're a mother . . .!" concern thing that implies you shouldn't be doing these dangerous things now that you have a kid?

I'm actually 15 weeks pregnant right now and doing dogsled tours with my dogs and running my sled, and snow machining my two-year-old out to daycare and to work.

That doesn't happen up here. There is no judgment here. But I'm positive if I went back home to Texas and told my old neighbors that I'm pregnant and snow machining around with a two-year-old and that's just how we have to live our life, I would get the old, "Bless your heart."

Oh no, the worst!

I think about this every time I go back down to the lower 48 to visit my family or friends. We have a tiny little mirror in our cabin that is like 6" x 6" square, and that's it. And everything else is just like, you don't even have time to look at yourself. You're hauling water, feeding 30 dogs, running puppies around, making sure everybody is happy and then you're exhausted at the end of the day and you go to bed and you get up in the morning and you do it all over again.

You can't take a shower, there's no running water, you probably smell bad, and you're probably covered in dog hair. But nothing else matters. You don't have time for anything else to matter or for anything superficial to matter. So then when I go to the lower 48 and I see commercials and magazines and I'm in my sister's house where there are big mirrors everywhere and I'm like, "This is what I look like? Do I look wrong? Am I supposed to be wearing makeup? Am I supposed to pluck my eyebrows?" It's just really horrible. Sorry, I'm totally rambling because I never talk to anybody.

No, it's really interesting. Back to the races, of all of the harrowing moments that you detail being out in races and on runs with the dogs where nature is doing its thing and the dogs are doing their thing or you've made a mistake, as a reader the only time that I really seized up and felt it was super dangerous was this. Without spoiling it for people reading this interview before they read the book, there was one major difference between the Yukon Quest and the Iditarod that you highlighted in the book: human obstacles, or human threats, were introduced in the Iditarod that weren't there in the Yukon Quest. Was that an isolated weirdness of the year that you ran that race, or is the rise in awareness or visibility of the race attracting weirdos, for lack of a better word?

I hope to think that that was a complete isolated event, but I know that the snowmachiners . . . I don't know if I can ruin this one for anyone, but it was in the news when the drunk snow machiner hit Jeff and Aliy's team and killed one of Jeff's dogs. I know that that has happened before. The whole thing that happened with me and Sarah was such a shock to both of us and the most unexpected thing ever. I really hope that that has never happened before and won't happen again, but I just don't know.

The fact that that can happen to people who are total strangers mushing by on a dog sled, I just don't know. Like when I've gone and visited New York City and I'm walking around at night I have a heightened sense of, "OK, I gotta carry my keys in my hand like this," and I'm always looking for an exit and a really super hyper-aware of my surroundings in that way.

On the trail in Alaska that's a whole instinct that I have forgotten in the last 10 years. So to all of a sudden have it come back in the most unexpected of places, it really threw me for a loop, and I felt really messed up about it because your priorities are very important but very simple when you're running a place like that: Take care of your dogs, take care of yourself so that you can take care of your dogs. Pay attention to the river ice. If something sounds weird, get to the shoreline. If someone goes in the ice, mush ahead of them and pull their team out. That's what you're thinking. You're not thinking about some random drug-addled weirdo coming out and trying to grab your ass or pull you off your sled. I'd like to think that was a really isolated incident, but I don't know.

You moved to Alaska to start over after a divorce. If anyone is reading this book or reading about this book and is thinking about doing that instead of cutting bangs or whatever most people do after a breakup, what should they know before they chuck everything and move out into the wild that you wish you had known before you did that?

Well, there's two things. I've really come to see this now that I am in a happy relationship. When you are in a relationship a lot of the times you get used to asking for help and getting that help right away, like, "Oh, I can't open this thing." Or, "I don't feel like carrying this heavy thing of propane in. Will you get it, you're the guy." There is no one to ask for help. You have to do the thing that you don't feel like doing every day and doing that over and over again, it toughens you up and it hardens you, in good ways and bad ways. You become self-sufficient. You don't need anybody else. But everyone needs love in their life and everyone needs community. It does end up becoming kind of difficult to find that balance.

Then the other thing is there is nowhere to hide from your grief or from any emotion. I think in a modern society where you are faced with your job and people around you every day you kind of talk a lot of things away, and don't deal with them right away, but up here you have to deal with them right away. Not only your grief or sadness, but also if something breaks you have to fix it right now otherwise if you can't get the heater working again and it's 40 below, you're going to freeze to death. You basically can't hide from anything, whether it is stuff that breaks and you don't feel like fixing or your emotions that you don't feel like dealing with, it's all pretty starkly right there in front of your face and you have to deal with it, for better or worse.

There's no such thing as running away to the woods to hide then?

Exactly.

Shares