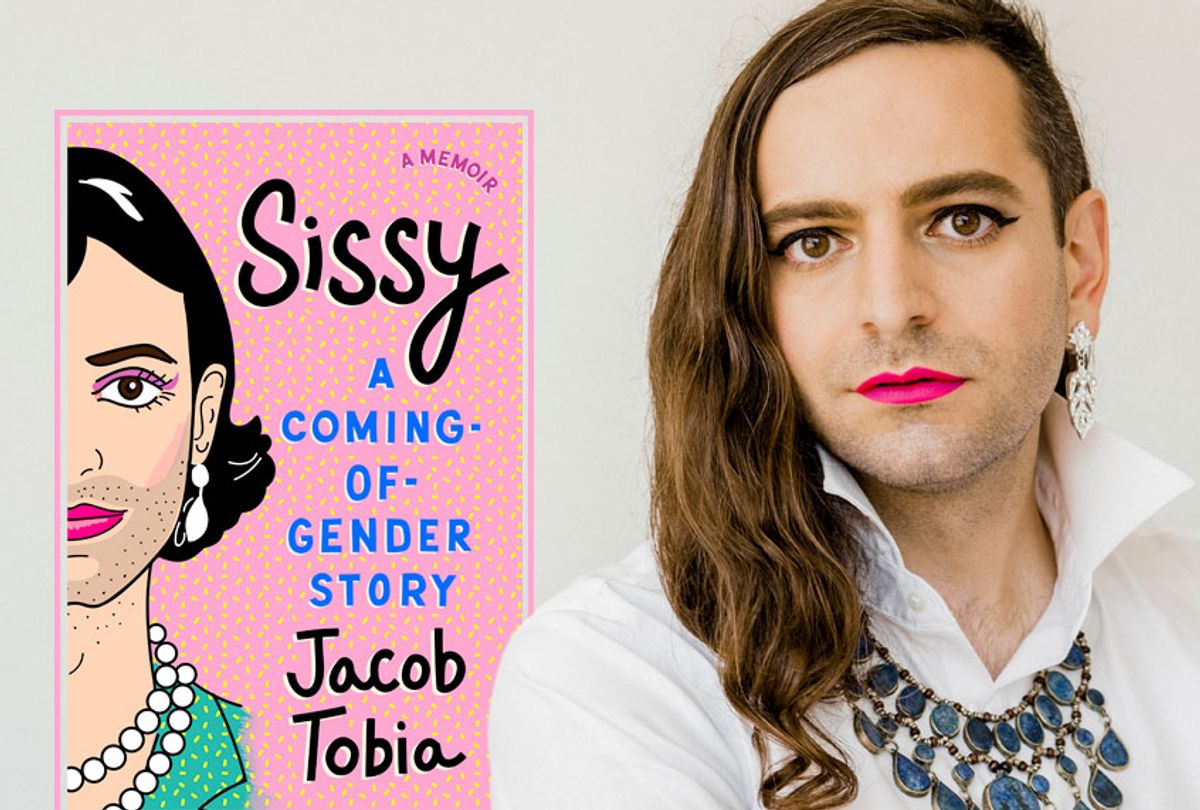

The cover of Jacob Tobia's new memoir, "Sissy: A Coming-of-Gender Story," is simply gorgeous. A drawing of half of Tobia's face is instantly captivating — their lid punctuated with a fuchsia pink cat-eye, their blush like a line in the sand between the smoothness and stubble of their facial hair, and their bright ruby lipstick somehow still managing to pop among the gradations of pink. The bubblegum background glitters with gold flecks.

You can judge "Sissy" by its cover, in that it evokes glamour, solitude, humor, and resilience, which are all key components to Tobia's vulnerable, moving story of what it means to grow up gender nonconforming in a gender-policed world.

"In our world as it is today, it isn’t a question of whether you’ve had gender-based trauma in your childhood," Tobia writes in the introduction. "Everyone has had some. Rather it’s a question of what degree of gender-based trauma you’ve experienced, what degree of distance you felt from your body and your peers. We all need to heal on one level or another. Through sharing my experiences on the margins, I’m aiming right for the center, for the core of how gender hurts us all."

In our interview, Tobia explains the depth of "Sissy," why they're not interested in writing "Trans 101," and how the rising visibility of the trans community has been threatened by exceptional backlash.

The message of your memoir is universal: that gender hurts us all and that we all have our own coming-of-gender stories. Was that your starting point when thinking about writing this memoir? How has your own experience — as well as witnessing others’ across the gender spectrum — motivated you to make this the central argument in your book?

I don’t think I could’ve stopped this book if I wanted to. It was bursting out of me. Navigating the world as a gender nonconforming person, I’m constantly being stared at. Some of the stares are insidious or threatening, meant to intimidate me or make me feel afraid. But the overwhelming majority of them are stares of curiosity. People see my male body in a dress and instantly their interest is piqued. They want to know more. They want an explanation of how this can be. And so I found myself, in thousands of tiny interactions with strangers and friends and loved ones alike, trying to explain the totality of my gender in short, two-to-three minute conversations. At a certain point, I grew exhausted of abbreviating my gender, of explaining it simply and without context. Writing "Sissy" began as an attempt to explain my experience with gender as fully as I could, but it quickly became so much more than that. It became my process of healing in public, of unpacking my trauma and sadness and frustration with the world and arranging them for everyone to see.

Quickly, the book unfurled beyond my own experience. I believe it when I say that everyone has gender-based trauma. Even the most masculine man or the most feminine woman have experienced loads of it. Gender policing is an abusive process that hurts everyone and dehumanizes all of us. In writing "Sissy," I’ve taken my glitter cannon and pointed it at the heart of gender shame and trauma. My goal is that reading this book and sitting with my story will blow open your gender, too. I want everyone to share their coming-of-gender story. I want everyone to know how they became who they are. And I want everyone to heal.

You've been very clear that you're not writing a "Trans 101" book, in the way that people from marginalized communities are often tasked with educating the public on their humanity. Was that difficult to negotiate? How did you think about bringing readers in without diluting your experience?

I refuse to do "Trans 101" again, and by that I mean that I refuse to talk about gender as if it is merely an intellectual concept that requires academic understanding. Gender is all heart. We feel gender most strongly, not with our genitals or with our brains, but in our hearts. It’s about blood and sweat and tears and sadness and joy and love and bliss. Gender, by its inherent affective nature, can never be simple or merely academic.

I don’t want to talk about what being trans means so much as I want to talk about how being trans feels. Teaching people to understand trans and gender nonconforming people empirically will never get us very far, but teaching people to feel for and with trans and gender nonconforming people can change the world.

That’s the strategy I’ve taken with "Sissy." I don’t teach readers the difference between the terms "gender nonconforming," "transgender," "nonbinary," "agender," "gender fluid" and so many others. I don’t give an empirical account of how many trans and gender nonconforming people there are in the world. Instead, I’ve chosen to share from the heart. To take people into my psyche, to feel what I felt. I think that is an education more valuable than any other, because the truth is that the terminology will never matter as much as the emotions, the story.

You speak about the need for not just rethinking gender, but a broadening of what it means to be trans. Can you explain this? Is this part of why it was important to amplify your upbringing in the church?

Trans identity is so much bigger than we give it credit for. In order to make trans experiences easier to digest for a cisgender audience, we’ve given up much of the flavor and nutrition and roughage. Not all trans people knew that they were trans from birth; not all trans people feel trapped in the wrong body; not all trans people want to transition medically; Some trans men are bottoms; some trans women are tops. At every step of the way, trans experience resists being oversimplified, and that’s what it’s all about. There is no right way to be trans. And just because someone’s trans story isn’t easily digestible, doesn’t mean that their story should be erased. As a culture, we need complex trans stories more than ever. We need to give trans people the gift of depth and nuance and inconsistency and complication. And as trans storytellers, we must always remind ourselves that that’s what we are owed.

My trans story is perhaps different than what people are used to. I grew up in the South, in North Carolina, and loved living there. I grew up in the church and, while it was complicated at times, [I] identify as a person of faith. I’ve never felt trapped in my body, only in the expectations that the world puts on it. I do not want to be a woman or a man so much as I want to be a messy glittery queen. I am raunchy and irreverent and unapologetic and completely unsuitable for polite company. As a trans storyteller, I’m often treated with ambivalence by movement leaders who want my story to be less complicated, to be "simplified for middle America." I refuse to do that because I came from middle America. Middle America can understand this story. Middle America is capable of loving people like me. I know this because, during my childhood and adolescence in North Carolina, they already have!

You call for nuance in "Sissy," but you also call for humor when it comes to conversations around gender. There was the whole controversy around Kevin Hart and past homophobic jokes when he was tapped to host the Oscars and Dave Chappelle really came under fire for transphobic jokes in his most recent specials, and the issue centered on the reality that the LGBTQ community still faces so much violence, and thus, jokes about their livelihood are never funny. How do we bring humor to the gender conversation when trans people still face so much violence for even just existing?

There is something profoundly powerful about laughing in the face of your oppressors. No movement survives without a sense of humor, because comedy is how we nourish our souls. Laughter is how we keep going when the going is tough. The moment that we give up laughter, we let those who are oppressing us win.

In writing "Sissy," humor was not only a creative challenge for me, it was also a means to heal. I forced myself to find the comedy in my darkest moments, because it makes them feel lighter. Because when I learn to laugh at what traumatized me, I open up space to actually heal from it.

All that being said, who’s making the joke matters. It’s never chill for cisgender guys to make fun of trans folks. Trans people cannot be the butt of a cisgender joke. That’s just violence. When Kevin Hart joked about how he’d hit his son if he caught him playing with a dollhouse, there’s nothing funny there. There’s nothing clever. There’s nothing witty. It’s violence, plain and simple, and he owes the trans and queer community — particularly trans and queer people of color — a real apology.

When people with power make jokes about people who have less, that’s oppression. When people with less power make jokes about people who have more, that’s liberation.

As you describe your childhood in "Sissy," there's some really horrific experiences of bullying and shaming that you share. Yet, you also note a real sense of freedom that you felt as a very young child, before that gender-shaming came. You show really brilliantly how this shame, around body and identity, is taught and passed down. How painful or liberating was that to revisit?

Oh god. I mean, I was a mess writing this book. And I can only really write in coffeehouses or bars, so I was a very public mess. I’ve cried in a Starbucks, just openly sobbed, more times than I can count. Whenever I revisit how cruel the world was to me as a feminine child, I’m filled with regret. Or maybe regret’s not the right word. It’s more like lament. Revisiting my childhood, I’m filled with acute, passionate, overwhelming grief. I wish so much for a different world for my child self. I wish I could do something to stop the people and institutions that were erasing me.

But revisiting the pain is worth it. It’s worth it. Because only through revisiting the cruelty of trans/queer adolescence can we end that cruelty. As a child, the most disturbing thing about the desecration of my gender was how normalized it was. Violence and neglect are the norm for feminine boys. As if we deserve that. As if we, at the tender age of two, brought it upon ourselves. It’s horrible to revisit, to see how the people in my life who cared for me were often powerless to save me from the cruelty of the world around me, but it is imperative if the world is ever to change.

And underneath all the pain, there are moments of sublime tenderness. There are beautiful, perfect, precious moments when women in my life tried to protect me or give me an outlet to express myself. There are gorgeous stories of resistance — fleeting moments of absolute liberation.

Powerfully, you also showed how — because of the bullying — you had to choose between being yourself and your safety. And with the mental health crisis that that caused, you illustrated how gender policing is life-threatening. Is that navigation between safety and your identity something you're still forced to endure?

Oh, everyday. In my adult life, I still have to make a daily choice between expressing my femininity and feeling safe. Each time I leave the house in a skirt, I’m on high alert, worried that today is the day that someone is going to catcall me or harass me or assault me or attack me, or worse. No amount of fame or visibility or money buys you the right to be gender nonconforming in this world. With money, you can perhaps afford privacy, but you can’t buy the right to walk in public free from harassment on any given Tuesday.

These days, I’m committed to being a survivor, not a martyr. I take steps to protect myself. If it helps me feel safe, I take cabs even when I’d rather walk. I put on pants, even if I’d ideally like to wear a dress, when I’m feeling unsafe or vulnerable. I take off my lipstick and my earrings if I feel threatened. When I fly (which I do for work a lot) I often opt to wear a simpler outfit — a t-shirt and jeans, no frills — to avoid stares, so that I can use gendered restrooms at the airport comfortably. I wish I lived in a world where I didn’t have to make those choices. I am confident that together we can build that world. But until then, I have to protect myself. It takes buckets of courage and wisdom and self-love to protect yourself in a world set against your actualization.

Thank you for sharing that. In "Sissy," you talk about “the Trans Tipping Point” and the growing visibility of trans people, but simultaneously trans people continue to face serious discrimination and violence via both individual harassment and public policy. How does this time and the writing of your memoir lead you to think about the current plight of the trans community and the future? How, as you wrote, has your own healing and the work of healing the world blurred?

The "Trans Tipping Point," as it was coined by Time Magazine in 2014, was part of a massive groundswell of progressive policy and energy that has since been met with some of the greatest backlash we’ve ever seen. There are legislative attempts across the country to criminalize trans identity — via restrictions on bathrooms, ID documents, access to healthcare and so many other issues — and strip us of any legal protections that we already have. That’s the trouble with visibility: when a community first gains mainstream visibility, that visibility almost always invites backlash.

In this moment of backlash, "Sissy" feels like a more vital and political text than ever. Through its humor, I hope that "Sissy" will give trans and queer folks the opportunity for some much-needed, life-sustaining laughter. I hope it will provide a respite from the world outside: a sacred space where my trans siblings can simply be with me on the page.

And I also hope that it will serve as a translational text, that in the tradition of personalities like Ellen DeGeneres and Laverne Cox, "Sissy" will help people fall in love with nonbinary and gender nonconforming people like me.

Above all, "Sissy" is my way of taking a stand, of saying that I refuse to cede the political ground we’ve gained, that I refuse to be put back into any sort of closet, that people like me have always been and will always be, and that we are here to stay.

Shares